From Dormitory to Animalia: The best Middle Eastern movies of 2023

The shadow of 7 October looms large over Middle Eastern film, putting in doubt the place of the region’s cinema within a global order, which treats our politics with increased scrutiny.

Every year, Middle Eastern cinema is confronted with familiar existential threats. Regional funds are inadequate and rulers are hostile to independent voices.

European money and streaming deals are indispensable, and while various bodies have shown commitment to Middle Eastern projects, foreign funding for politically challenging films has become precarious.

The Middle Eastern independent film scene is thus inundated with uncertainty.

Each country faces a set of unpredictable obstacles: In Algeria funding is decreasing, while in Tunisia it depends on the temperament of governing cultural figures.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Iran and Turkey have been hit by waves of censorship; Sudan’s hopes for a bourgeoning cinema have been derailed by war.

Lebanon is yet to emerge from the shadow of the Beirut explosion; Palestine is vulnerable because of the timidity of European funders, whose cultural policies are shaped by their governments.

In Egypt the focus is on churning out commercial fares and frothy entertainment for regional streaming services.

In the midst of this snowballing instability in the independent scene, Saudi Arabia has emerged as the powerhouse of cinema in the region.

With the most lucrative box office in the region and a prodigious streaming service, MBC’s Shahid, the leading producer of Arab content, the kingdom is a fast-growing market attracting storytellers from every corner of the region.

Even Netflix, once heralded as the saviour of Middle Eastern drama, has shifted its full focus on to Riyadh: Three of the network’s scant Middle Eastern productions in 2023 happened to be Saudi films: Alkhallat+, The Matchmaker and Naga.

What the year has thus revealed is the growing gap between the commercial and independent.

With dwindling revenues, the extinction of indie producers, and the inability to both unearth alternative means of funding and penetrate new markets, independent films continue to face an uncertain future, a reality that remains unchanged since the pre-streaming days.

In the post-7 October world, however, the need for free, authentic, ingenious voices in Middle Eastern cinema has never been more pressing.

Cumulating forces, be they Western or Middle Eastern, grapple to shape, and domesticate Middle Eastern talents. The resilience of Middle Eastern filmmakers to combat and break free from these powers is what shall determine the future of the region’s cinema.

The best Middle Eastern offerings of 2023 are both a testament to the evolution of regional cinema and a reminder of the exceptional art endangered by the forces of commerce and conservative politics.

The story of Middle Eastern cinema continues to take unexpected turns, and 2023 is another unwieldy chapter.

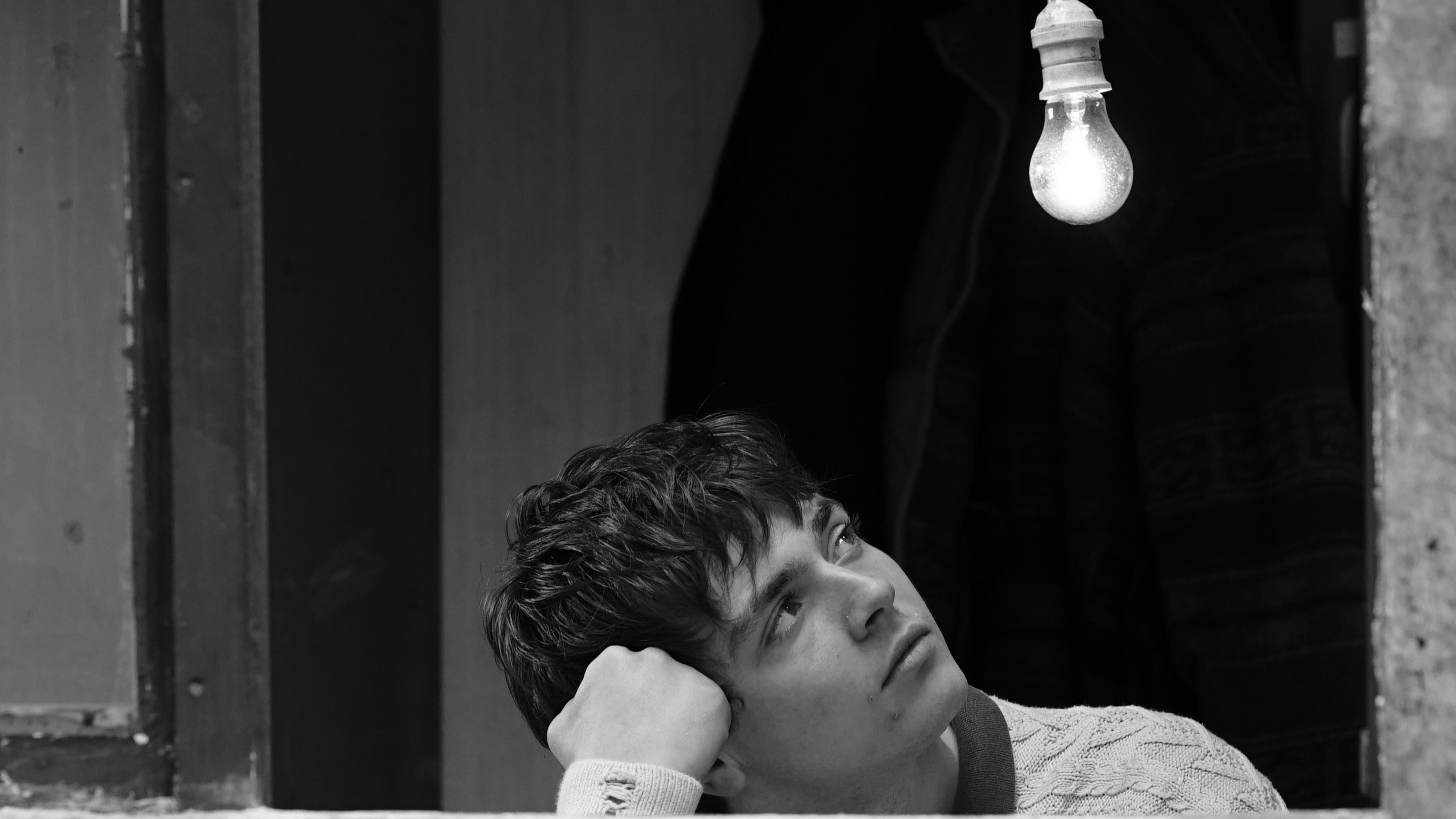

10. Dormitory (Nehir Tuna)

A guileless adolescent finds himself torn between his secular upper-class school and the oppressive Islamic dormitory where his businessman father has forcibly enlisted him in this striking, perceptive Turkish debut feature.

Set in 1996, a period of tension between traditional secularists and newly empowered Islamists, Yurt is, by turns, a study of class disjuncture; a shrewd exploration of the relationship between class and political Islam; and a snapshot of a pivotal juncture in Turkey’s modern history.

It covers a period that serves as a transformative point in Turkish history, one marked by a social tear that has only grown wider in subsequent decades.

Gorgeously photographed in black and white, Dormitory is a moody coming-of-age story with the kind of subtle but forceful politics seldom seen in Turkish films of late.

9. Hounds (Kamal Lazraq)

Kamal Lazraq’s gritty debut feature set in Casablanca is a slice-of-life thriller that harkens to classic South American genre cinema, albeit with a distinctively Moroccan touch and deliciously acerbic pitch-black humour.

A gangster hires a middle-aged unemployed man to kidnap the lowlife goon who murdered his dog in a canine fight. Bringing his teenage son along, the two accidentally kill the thug, one of many luckless calamities that force the pair to dispose of the body before dawn.

Sharing the broodiness, and edginess of Nour Eddine Lakhmari’s underrated noirs, Hounds, which earned the Jury Prize in the "Un certain regard" competition at Cannes, is an uncompressing look at Morocco’s underbelly realised with gusto and unflinching realism.

The peculiarly engaging father-son relationship points to a generational disjunction and the shifting values of a nation whose ideals are increasingly shaped by its perpetually tattered economy.

Highly entertaining and amusingly violent, Hounds is a jagged ride into the heart of darkness.

8. Inshallah a Boy (Amjad Al Rasheed)

The first Jordanian film to make it on to this list is arguably the country’s boldest movie to date.

Palestinian thespian Mouna Hawa (Fauda) is the recently widowed young mother Nawal who lies about her pregnancy in order to save her inheritance from her brother-in-law.

A fierce indictment of Jordan’s chauvinistic inheritance law conceived as a ticking-bomb feminist thriller, Inshallah a Boy compensates for the didacticism of its third act with adroit editing and muscular writing that cunningly takes a swipe at Islamic scriptures while championing women’s sexual autonomy.

Adopting an uncluttered visual style emphasising the claustrophobic relationship between its characters and their confined surroundings, Al Rasheed’s stout debut is another stepping stone in Jordan’s budding cinema scene.

7. Goodbye Julia (Mohamed Kordofani)

On paper, Mohamed Kordofani’s debut feature sounded like a recipe for disaster: a woman's film featuring a Southern Sudanese maid protagonist written by a man from the north.

What we ultimately get, however, is a deeply sensitive melodrama about a country that no longer exists; a vivid portrait for a past Sudan ravaged by class, racism and patriarchy.

Set on the eve of the 2011 South Sudanese independence referendum, Siran Riak plays the eponymous Southerner housewife who is hired by a Northern middle-class ex-singer responsible for the death of the former’s husband.

What begins as story of an elusive quest for redemption swiftly develops into a tender tale of interracial female friendship threatened by self-serving patriarchy.

Deliberately paced and exquisitely performed by its two female leads, Goodbye Julia doesn’t conceal its nostalgic longing of a united Sudan, yet it admirably never denies the complicity of the North in the systematic marginalisation and racism of its former sub-Saharan black population, a complicity that extends to the director’s younger self.

6. My Worst Enemy (Mehran Tamadon)

The most criminally overlooked Middle Eastern picture of the year is also the most provocative, chilling title on the list.

Paris-based Iranian documentarian and satirist Tamadon sets a fanciful target for his fourth feature: to re-enact the sadistic interrogation and torture political prisoners endured in his home country and present the outcome to the intelligence officers, naively believing that the film may awaken their conscience.

Tamadon enlists Zar Amir Ebrahimi, fellow exile and star of Holy Spider, while casting himself in the role of the interrogated detainee.

Things do not go as neatly as planned and what starts as off a nifty exercise in role play swiftly turns into an incisive examination of the director’s haughty motives, the limitations of the medium, the questionable ethics of the genre, and the true utility of filmmaking.

Unnerving and multilayered, My Worst Enemy is the reenactment film to end all reenactment films.

5. Bye Bye Tiberias (Lina Soualem)

In the wake of 7 October, the smashing success of Lina Soualem’s documentary feature has been one of the few hopeful happenings for Palestinian cinema.

For her sophomore effort, the Palestinian-Algerian filmmaker turns her camera on her mother, Hiam Abbas, Palestine and the Arab World’s most acclaimed actress, conjuring up an intimate portrait of a homecoming fraught with complex family dynamics, unresolved histories, and a haunting sense of loss.

Soualem expertly blends the personal and the political, utilising the disparate members of her large colourful family to dissect the decades-long impact of the Nakba.

Archival footage and home videos punctuate an irresistibly affecting narrative whose power comes into bloom in the shattering conclusion.

At a time when Palestinian narratives are deliberately buried on the Western stage, the success of Bye Bye Tiberias, a film that tackles the Palestinian affliction with remarkable delicacy, soberness and maturity, is proof that the global public remains further ahead of its morally compromised politicians.

4. In the Blind Spot (Ayse Polat)

In a year of outstanding works from diasporic Middle Eastern filmmakers, Ayse Polat’s sixth and best feature is a particular standout.

An investigation into Kurdish disappearances in Turkey rapidly leads to a murder of a rogue member of a state-sanctioned hit squad.

The mystery of that central event is revealed over the course of three chapters representing three different points of view.

The taboo-breaking political commentary on the Kurdish prosecution by the Erdogan government is woven into a nail-biting, tightly-knotted political thriller rich with subtext on the mutable role of the camera in a world where privacy is impossible.

Polat’s Turkey is a grand prison akin to Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon: an expansive system of control where citizens are always kept under surveillance.

In this paranoia-infused universe, the camera is paradoxically rendered as both a method for truth-seeking and a tool of domination.

Polat’s Turkey is no mere isolated totalitarian state - it’s a symbol of a modern world where citizens willingly and unwillingly give away their freedoms in exchange for an unsustainable stability.

3. Mother of All Lies (Asmae El Moudir)

It’s been a vintage year for Arab documentaries, and Asmae El Moudir’s surprise Moroccan breakaway hit is among the finest.

A dual winner in Cannes for best documentary and best direction in Un certain regard, El Moudir recreates her childhood home in the form of a scale model populated with numerous figurines who represent the old inhabitants of her old Casablanca district - a reaction towards the conspicuous absence of any childhood photos of herself.

The cutesy ambience of what initially appears to be a family homage is soon replaced by darker probing involving the violent 1981 bread riots and the collective amnesia forced upon a populace that has never truly come to terms with its bloody past.

Winner of the 2023 Best Director prize in Cannes’ Un Certain Regard 🏆

— TIFF (@TIFF_NET) July 26, 2023

The North American Premiere of THE MOTHER OF ALL LIES follows director Asmae El Moudir as she uses hand-made figurines to uncover layers of personal and political history. #TIFF23 https://t.co/gpte44CXGC pic.twitter.com/Tfj2F9fFJP

The director’s dismissive, cantankerous grandmother - the unrivalled star of the film - resists her granddaughter’s inquisitive gaze, constantly disrupting the power dynamics of the film’s making.

The Arabic title of Moudir’s brilliantly inventive second feature is Kedba beeda (White Lie): the harmless lies we tell ourselves and our children to move on; to forget; to bury the scorching traumas.

But, as El Moudir hints, the lies of the past conceal the bigger lies of the present - lies neither the director nor any of the filmmakers of her generation have been allowed to confront.

2. About Dry Grass (Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

Deniz Celiloglu’s Samet is possibly the year’s most narcissistic protagonist: an insufferably self-absorbed schoolteacher trapped in a modest village he utterly disdains.

His hopes of securing a desperately coveted transfer to Istanbul are jeopardised when two of his students accuse him of misconduct.

But this is not yet another habitual tale of masculine abuse of power, for in the hands of Turkey’s greatest living filmmaker, this wayward classroom drama becomes a microcosm of a nation paralysed by its officiousness and insecurities; a study of a generation of men too vain and too frail to face up to their mediocrity; a forensic dissection of the institutional addiction to maintaining a prospectless, soul-crushing status quo.

Lasting nearly three and a half hours, Ceylan’s ninth feature is endlessly talky, raw in its emotions, and frequently queasy.

It’s also one of the most absorbing watches of the year: a morally convoluted Chekhovian drama replete with broken characters stunted by a lack of self-awareness, or, more accurately, the terminal fear of apprehending their emotional, intellectual and physical limitations.

Ceylan has never been interested in creating sympathetic or easily categorised characters.

About Dry Grass is no different: a film that challenges, questions, and ultimately subverts human sympathy, propelling us to face our elevated position of the morally superior spectators, and ultimately unearths uncomfortable truths about not just the characters, but the viewers’ personal failings and unflattering prejudices.

1. Animalia (Sofia Alaoui)

Sofia Alaoui’s stunning Moroccan debut feature is the greatest Arab sci-fi film to date. This is not an overstatement; the handful of Arab sci-fi features released in the past century oscillated between camp and horror, the best of which adhere to classical narratives and explicitly laid-down themes.

Alaoui turns Arab sci-fi on its head, visually, thematically, and narratively, and the result is the most ambitious, most original Middle Eastern film of the year.

Transfixing newcomer Oumaima Barid is Itto, a heavily pregnant young wife married into a rich family headed by an unaccepting, domineering matriarch. Hailing from a poor Berber background, she is deemed by her mother-in-law as a social climber not good enough for her husband.

Itto’s world suddenly turns haywire when a mystifying occurrence that resembles an alien invasion drives animals mad, interrupts phone signals, and darkens the sky surrounding her luxurious suburban villa. Itto is then escorted on an unruly odyssey that shall forever change her.

This lucidly described plot could be deceptive, for Animalia is anything but traditional or straightforward in its narration.

Alaoui never reveals the particularities of this presumed alien invasion, which may not be alien to begin with. Meanwhile the ostensibly linear storytelling takes a radical shift in the last act to fully descend into a surreal, psychedelic dreamscape.

All the while, the director’s preoccupations steadily come to the fore: the difficulty of upward mobility in a country plagued by classism; the relationship between class and freedom of women in self-actualisation; the hollowness of organised religion and its ill-fitting position in modern life; and, most intriguing of all, the Berber identity that has been repressed by a monopolising Arab culture.

Animalia is a purely sensory experience that recontextualises the question of God and the universe within the ancient Berber belief of Animism - a direct correlation to the film’s title.

It’s an intrepid conceit that Alaoui pulls off with masterful dexterity and confidence rare for a debutant. Simply put, there’s nothing like Animalia in Middle Eastern cinema, a miracle of a film marking the birth of a new unique, visionary talent.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.