Middle East coral reefs: How sunscreen and mass tourism are taking a toll on marine life

“Amazing natural pools surrounded by corals, one of the best snorkelling sites in Dahab,” a 2017 Facebook review of popular snorkelling spot, Three Pools, says. Plenty of other reviews around that time agree.

They describe three idyllic coral-encrusted depressions in the top of a reef teeming with life, sandwiched between the clear blue waters of the Gulf of Aqaba and the mountains of the Sinai Peninsula.

The pools still attract thousands of day-trippers annually, despite the Covid-19 pandemic, from the nearby tourist town of Dahab, Egypt.

But these days a grim sight greets those who swim out to snorkel the pools. This once intricate web of vibrant life is now barren, colourless and full of signs pointing to a single culprit: humans.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Maxim Smirnov, a Russian dive instructor living in Dahab, says most of the deterioration at Three Pools occurred over the last three to four years: “It was totally different before! It was a magic place,” Smirnov tells Middle East Eye.

Now it’s often crammed with busloads of tour groups. They are a welcome relief to those relying on tourism to make ends meet. But underwater it is easy to see why the mass of bodies in the water at Three Pools and other popular diving and snorkelling sites in Dahab has sparked concern among more environmentally aware residents.

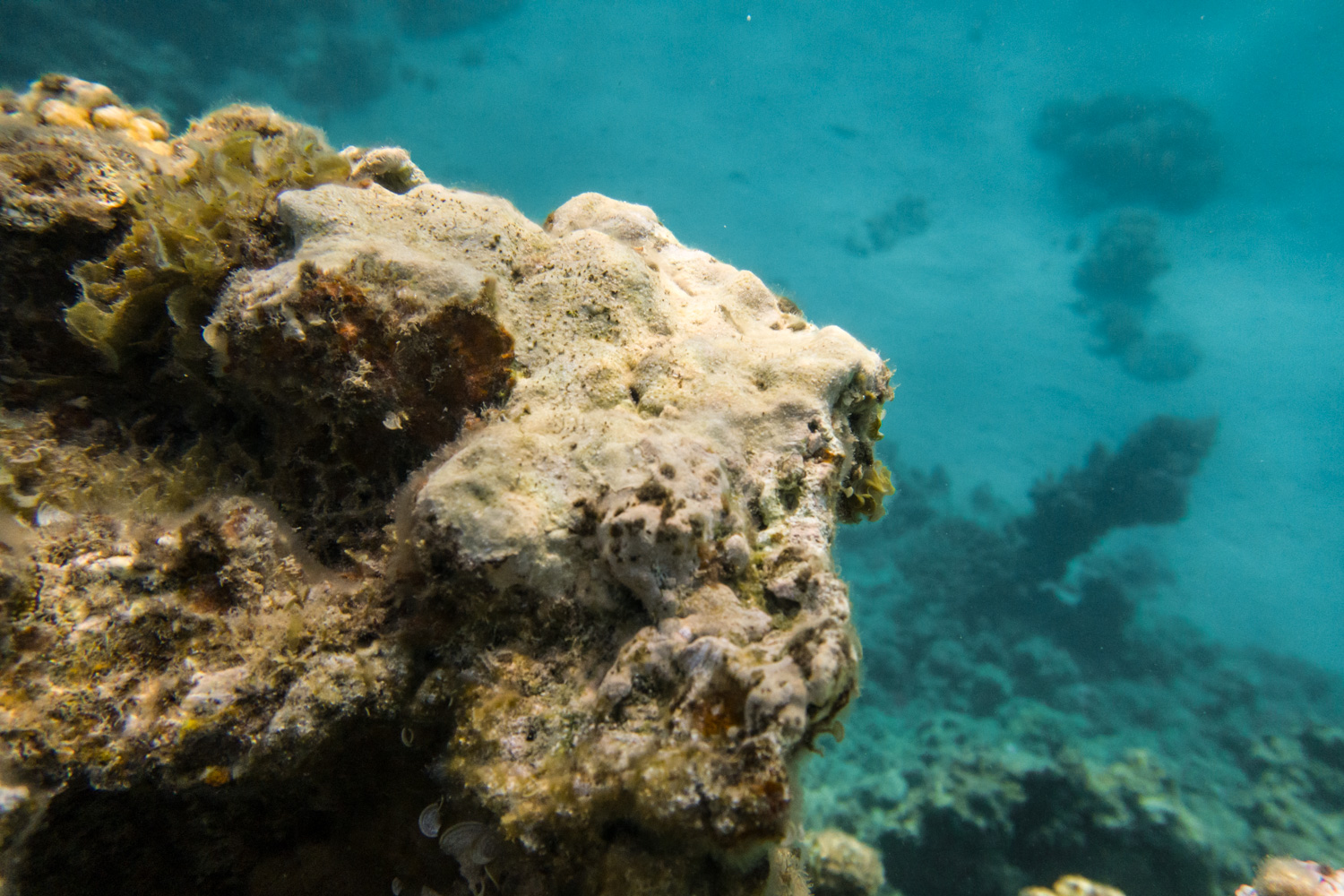

Beneath the surface the reef looks like it has psoriasis. Bare patches mottle what’s left of the corals, where weak swimmers have trampled or broken them with clumsy kicks.

Deeper down, beyond the reach of amateur divers, many grey, algae-covered coral skeletons are intact. What killed them is not so immediately obvious.

A shrill whistle sounds from the cafe-lined shore as a self-appointed reef monitor, who prefers to remain anonymous, gestures and yells for the umpteenth time at yet another group of holidaymakers standing on the reef top as they cool off in the water.

“They break the corals,” he says. But that isn’t all. He thinks the sun protection lotion people are slathering on themselves and their children may also be affecting marine life.

Sunscreen extremely toxic to corals

The idea that sunscreen negatively impacts aquatic ecology, especially corals, has gained traction through a growing body of scientific research.

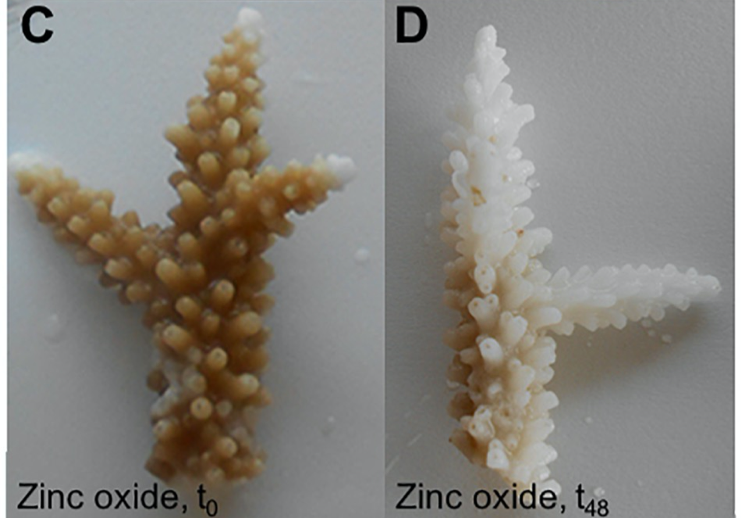

Cinzia Corinaldesi, ecology professor at Italy’s Universita Politecnica delle Marche and co-author of a 2018 paper on sunscreen and corals in the Maldives, found that zinc oxide nanoparticles often used in sunscreens cause “severe and fast coral bleaching”, even in minute quantities.

'When tourists and snorkellers swim inside [the reefs], their released sunscreen can affect corals more than open-sea areas'

- Cinzia Corinaldesi, ecology professor

Sunscreen from swimmers’ skin stagnating inside Three Pools, rather than being dispersed and diluted by the open sea, might explain why so many corals out of reach of swimmers have died.

“The presence of pools and the shallow depth hinder water exchange,” Corinaldesi tells Middle East Eye after seeing the site via video. “When tourists and snorkellers swim inside, their released sunscreen can affect corals more than open-sea areas.”

A few metres further out from the pools, where the reef slopes down to deeper, open water, the corals, while not flourishing, do seem in much better shape. And many less enclosed diving and snorkelling spots in Dahab still boast healthy looking, prolific coral cover.

Coral is not a single organism; it is made up of many coral polyps that form colonies. A special type of algae that lives inside the polyps gives them their colours and turns energy from sunlight into food. Coral bleaching describes what happens when coral polyps under stress eject the algae they depend on.

Just one drop of sunscreen in a litre of water is enough of a stressor to cause bleaching, Corinaldesi says. This is especially worrying in some tourist areas because they are “so overcrowded that the total amount of sunscreen released into the sea is thousands of tonnes per year”.

The problem is set to increase as the global sunscreen market has a projected five-year growth rate of over 5 percent each year, which Corinaldesi fears will increase quantities released into marine environments.

“Corals are already at risk from climate change and multiple stressors,” Coraldinesi says, “so if we don't start immediately reducing the sources of impact that we can manage easily, such as sunscreens, future generations will no longer have the chance to see them.”

Reef ecosystems also provide fundamental goods and services to humanity, supporting fisheries, tourism and healthy functioning of the marine ecosystem, she adds.

A global problem

Coral bleaching events around the world are often caused by warming sea temperatures, scientists say. Around Kish Island in the Arabian Gulf, coral bleaching does vary with the seasons, but not in the way we might expect.

Most of the coral bleaching here occurs during the slightly cooler winters, according to research from environmental and biological engineer, Dr Hamidreza Sharifan.

The stifling heat of summer in Iran means Kish is relatively quiet then. Winter is when the place really comes alive with visitors – leading to an estimated release of over three times the amount of four common, toxic-to-coral, sunscreen chemicals as in summer.

Comparing tourist numbers with bleaching rates across the year, Sharifan uncovered a direct correlation: corals on Kish bleach all year round, but more in winter months than summer, exactly coinciding with periods when more sunscreen enters the water.

He has also found evidence of negative impacts in the Gulf of Mexico. Other studies highlight issues in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans.

It is alarming, he says, and suspects this type of toxicity is not confined to sunscreens, but pervasive throughout personal care products “The results of ignorance will lead to catastrophic consequences,” he warns.

'Managerial void'

“Exposure to high amounts of sunscreen is just one of many consequences of unregulated mass tourism,” a Dahab-based environmental activist who prefers to remain anonymous tells Middle East Eye: “The corals at Three Pools are suffering due to the managerial void left by the responsible authorities."

He thinks Three Pools has been adversely affected by inorganic nutrients from wastewater and fibres from beach cushions blown into the water in stormy weather choking corals, as well as overcrowding and sunscreen. All four issues are preventable if managed effectively, he says.

His own time spent underwater has shown him first-hand how increasing visitor numbers affect some of Dahab’s top diving and snorkelling sites.

A petition set up by Dahab Defenders, a community group, has garnered 22,000 signatures in an attempt to save local areas around Three Pools and Blue Hole from overcrowding.

People are still flocking to places like Dahab because it offers so many open air relaxation and activity options

“None of the people who participate in tours to these places wants to harm the environment intentionally,” says the activist. Like Sharifan, he sees the consequences of ignorant commercial tourism operators led by unregulated, profit-oriented industries as dire.

Around 65 percent of Egypt’s total tourism volume is currently concentrated in the Red Sea and South Sinai Governorates, where Dahab is situated, Tourism and Antiquities Minister Khaled El-Enany told Reuters in April 2021.

Egyptian tourism stands at around half the 13 million annual visitors the country welcomed before the Covid-19 pandemic. But people are still flocking to places like Dahab because it offers so many open-air relaxation and activity options, which “is exactly what the tourist is seeking after Covid,” El-Enany told Reuters.

Numbers are set to increase further with five new charter flights between Russia and South Sinai that began in August after a six-year hiatus following the downing of a Russian jet from a bomb on board claimed by the Islamic State group.

The local activist suggests Egypt uses entry fees charged at places like the world-famous Blue Hole to better support and expand the region’s marine ranger network.

Enabling rangers to effectively enforce environmental protection laws already in place in Egypt since 1983 could enable Dahab’s spectacular reefs to remain a valuable asset to Egypt and the world, he says.

“The missing piece in the puzzle here is a government entity that really does its job properly.”

Government regulations and individual choices

Like Egypt, Thailand and Mexico have corals that have featured in sunscreen research. Both countries have begun implementing bans on sunscreens containing known coral killers.

The Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency and Ministry for Environment did not respond to Middle East Eye’s requests for comment on whether Egypt plans to follow suit. A branch of the Ministry for Tourism declined to comment.

Government organisation Eco Egypt launched a marine conservation campaign in June with an awareness-raising video cautioning against touching corals and recommending reef safe sunscreen. So far it has 5,600 views.

The sunscreen industry has reacted to growing toxicity concerns and bans by developing some lotions free from chemicals known as harmful to marine life. The New York Times-run product recommendation service, Wirecutter, rates one sunscreen as a winning option, in terms of scientist-advised ingredients, price and skin feel.

So far the industry isn’t required to regulate on using the term “reef-safe”, so checking the ingredient list as an eco-conscious consumer is important, according to EcoWatch.

For those assuming they are too far away from coral reefs for their sunscreen choices to matter, Ecowatch warns that wherever you are, when you shower your sunscreen enters the wastewater system and can easily end up in aquatic environments.

Corinaldesi emphasises the importance of consumers taking responsibility for their sunscreen product choices.

“Each of us can help save marine life by eliminating the use of non-environmentally friendly sunscreen products” she says. There’s no need to wait for a ban.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.