Ptolemy, Al-Sufi, and the Middle Eastern influence on cosmology

A red-turbaned camel herder chasing his beloved across the skies until she transcends the horizon into the night, remaining out of reach for eternity. That's the ancient tale of Thuraya (Pleiades) the disinterested object of affection for a determined Aldebaran, meaning 'the follower' in Arabic.

The legend was one of many ancient explanations for the star Aldebaran appearing to follow the Pleiades star cluster across the sky.

A region of space made up of 800 stars in the constellation Taurus, the Pleiades has inspired myths in myriad cultures globally. Some Islamic scholars even suggest that the objects referred to as Surah An-Najm (The Star) in the Quran are a reference to the cluster, which is also referred to as the Seven Sisters in English, Parveen in Persian, and Ulker in Turkish.

The myth of Thuraya and Aldebaran is just one of many tales told about the stars. In another, Suhail (the Arabic name for Canopus, the second brightest star in the sky) is the murderer of a man named Naesh, and is pursued by his victim’s daughters, the Banat Naesh.

In 1899, Richard Hinckley Allen, an American astronomer, published his book Star-Names and Their Meanings, which covers ancient Greco-Roman cosmology, as well as that of most of Asia, and highlighted the universality of star mythology.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Such fables provide a glimpse into the lives and beliefs that were held sacred by ancient communities and are loaded with symbolism that still hold value to this day.

They are a universal aspect of human history, with cultures from the Incas of South America to the ancient Egyptians developing their own cosmological lore.

Babylonians, Iranians and Arabs

The Babylonians were perhaps the first to document their study of the cosmos. During the Kassite rule (1595 – 1155 BCE) they etched their discoveries into tablets in cuneiform script, forming their own star catalogues.

The ancient Mesopotamian “MUL.APIN” compendium is the most well-known and earliest catalogue discovered so far.

Written evidence of the importance of stars in Elam, (ancient Iran) is scarce, but by the first century CE Sassanian kings were interested in astrology, translating Greek and Hindu astrological texts into Persian.

The Younger Avesta - an updated text to the original sacred Zoroastrian book the Avesta - mentions two constellations, Pleiades and Ursa Major, or the Great Bear.

According to the faith, Ursa Major was believed to protect Earth from wayward demons trying to enter the solar system from the depths of hell.

The Greeks also had their own well-established cosmology, associating stars with the deities of their pantheon.

Building on ancient Babylonian tales and Greek astronomy, Arab and later Islamic astronomers identified more celestial objects, leaving their mark on astronomy with at least 260 stars still having Arabic names in use today.

Al-Sufi and the cataloguing of the sky

For early Arab astronomers, the legends that had built up around stars were not just intriguing for their symbolism but they also served as a method of identification.

Myths about murderers being chased across skies were an easier way of explaining the cosmos than simply identifying and naming the distant sparkles of light visible at night.

Bedouin tales were incorporated into the writings of Abu Al-Husayn Abd Al-Rahman Al-Sufi, who was also known by his Latinised name Azophi in the Western world.

Sufi was a 10th century Persian astronomer who ran an observatory in Shiraz, Iran, where he studied the stars and the earlier works of Claudius Ptolemy, the first century Alexandrian Greek astronomer.

Ptolemy lived 800 years before Sufi and his work Syntaxis Mathematica describes and illustrates more than a thousand stars, arranging them into 48 constellations.

Sufi corrected some of Ptolemy’s observations and elaborated on his findings, which had been translated into Arabic in the 8th and 9th centuries in a book known as Al-Magesti, meaning 'the greatest' in Arabic (Almagest in Latin).

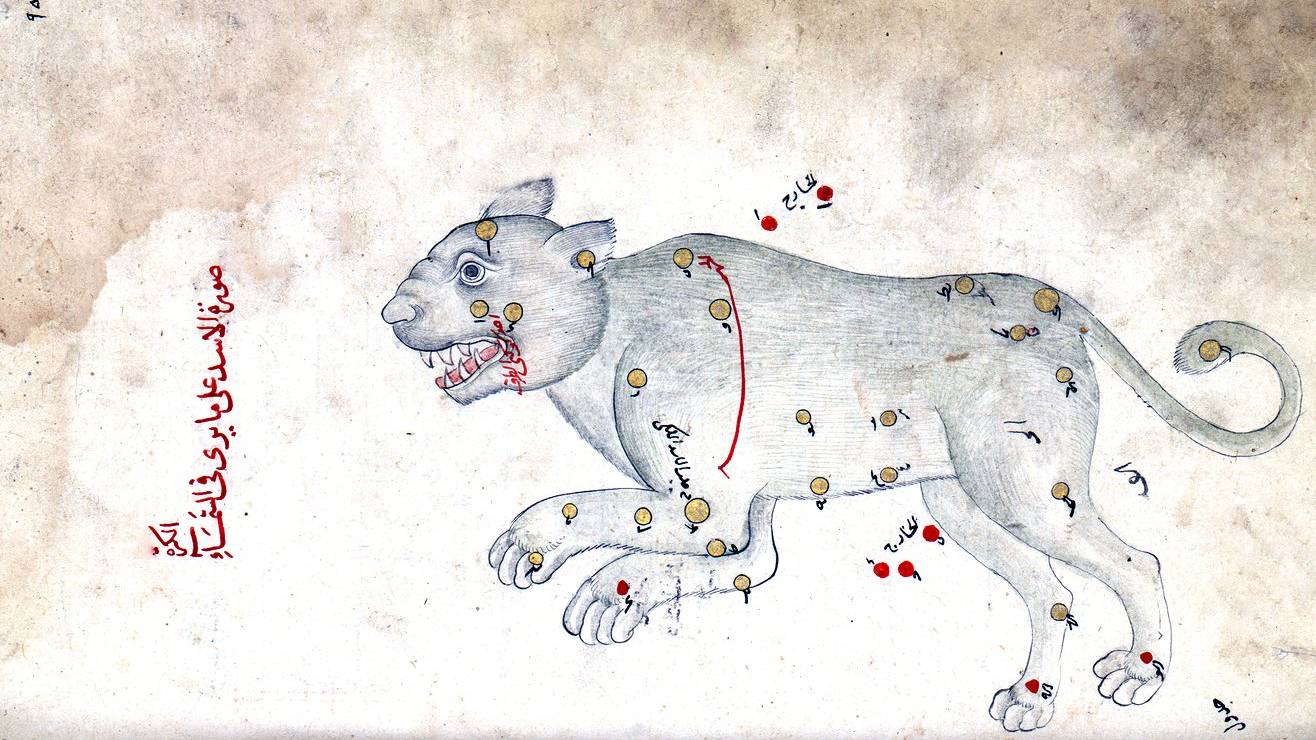

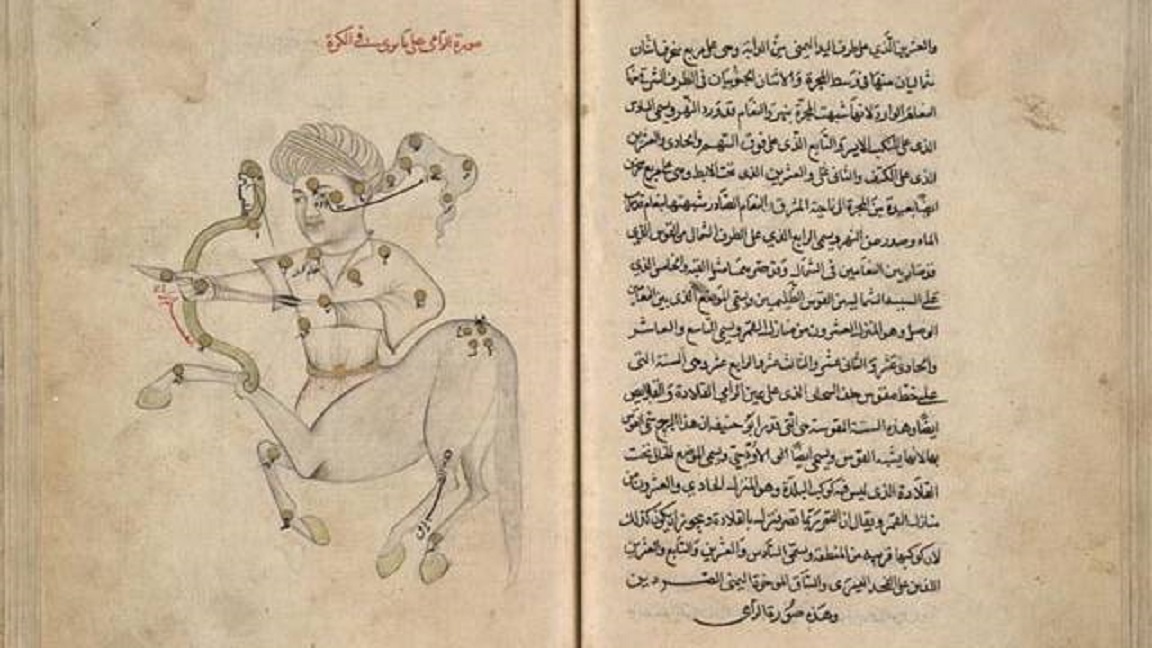

The Persian’s own work Kitab al-Kawakib al-Thabitah, (The Book of Fixed Stars) adopted Ptolmey’s plotting illustrations against constellations, such as a bear to represent Ursa Major (The Great Bear) and a lion to represent the constellation Leo.

For each constellation, Sufi drew a pair of drawings, one illustration showed how the constellation appears in the sky, and the other showing how it would appear in a celestial globe.

Other notable illustrations by Sufi included Al-Maraa Al-Musalsala, meaning “the chained woman’ for Andromeda, and Fum al-Hut, meaning “mouth of the whale”, which is today known in English as Fomalhaut, which is in the Piscis Austrinus constellation.

For centuries, Sufi’s work became a handbook for understanding constellations and was instrumental in preserving Ptolmey’s work for later western scholars.

The oldest surviving copy of Kitab al-Kawakib was produced by Sufi’s son in around 1010 CE and can be found at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

When Arabic texts, including Sufi’s codex, were translated into Latin at around the start of the 12th century, many of the originial names were changed beyond recognition.

One example includes Achernar, the brightest star at the southern tip of the Eridanus constellation. Its name comes from akhir al-nahr, which means “end of the river”.

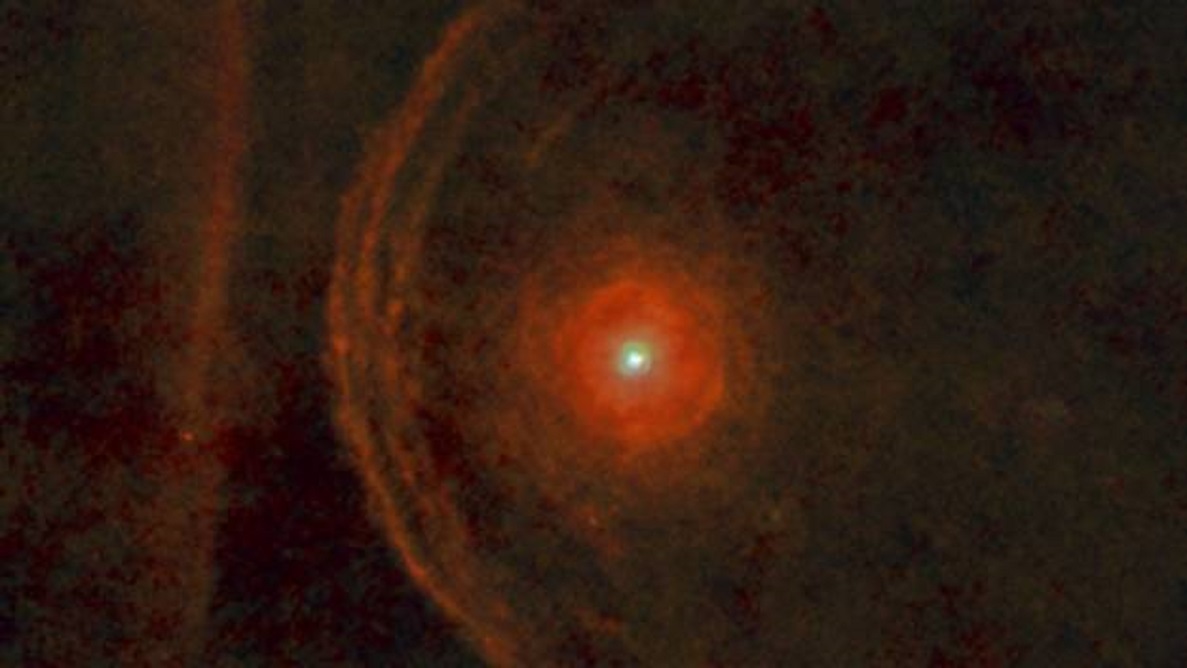

Fans of Star Trek and Star Wars might recognise Algol, which is a bright stellar system - a multiple star formation - in the constellation Perseus. Sometimes known as the Demon Star, its name in Arabic is Ras al-Ghoul, which means the "head of the demon". And the name of Betelgeuse, a red super giant in the Orion constellation, is derived from yad al-Jauza meaning “hand of the central one” or “hand of Orion”.

A standardised legacy

The International Astronomical Union (IAU), based in France, is the only official body that can name stars. In 2016, in order to prevent confusion stemming from different star naming conventions, it standardised the names of hundreds of stars, including those derived from Arabic originals.

Names featuring in Sufi’s catalogue written a thousand years earlier were formerly codified for use by future astronomers.

Several of these stars feature in Ursa Major, also known as the Big Dipper or Al-Dubb Al-Akbar (Great Bear) in Arabic.

The top star of the constellation is named Alkaid, derived from the Arabic al-qaid, meaning "leader". In Arab cosmological lore it is sometimes called Al-Qaid Banat Al-Naaesh or “The Leader of Naeesh’s Daughters” from whom Suhail was trying to escape.

Along the Great Bear's tail there is Mizar, which means loincloth in Arabic, then Mirak, which comes from maraqq, meaning "loins". Alioth sits further along the tail, where it widens, and is thought to come from alyat, meaning the 'fat tail of a sheep'. Megrez is taken from maghraz, which means root of the tail.

Then there are; Phecda, from fakhdha meaning "leg" and Dubhe, which means bear in Arabic.

Over the centuries, and as the study of the night sky has become globalised, the names the ancients used for celestial objects have converged into a unified lexicon formed of Latin, Greek and Arabic names, among others.

As a result, Sufi's catalogue - inspired by Ptolemy and the myths of Bedouin stargazers millenia ago - will likely continue to influence astrononomers for centuries to come.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.