Evil eye: Five ways people in the Middle East ward it off

It's a scene many of those raised in or around Middle Eastern cultures will be familiar with, and one that can be a cause of anxiety for some.

“Oh, hasn’t he grown into a handsome young boy," a doting well-wisher will say, and the said child's mother will wait anxiously for the compliment to be followed up with the Arabic phrase mashallah - "God has willed it".

After realising the blessing is not going to be offered, the mother says mashallah herself and starts muttering prayers under her breath to protect her child, now suspecting her acquaintance could have placed the ain, or evil eye, on her child, sometimes by the slip of the mind and occasionally on purpose.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The belief in the evil eye, which roughly corresponds to the concept of envy or the "green-eyed" in western cultures, is widespread in the Middle East. In Arabic it is known as ain, meaning eye; in Turkish it is known as nazar, meaning gaze, and in Persian it is called cheshm.

A lingering gaze from an envious eye, not immediately followed by a blessing, can lead to all sorts of affliction. Many believe it to be responsible for the misfortunes they encounter and go to great lengths to ward off its supposed powers with rituals rooted both in religious practice and cultural traditions.

In one widely shared anecdote, an Iraqi woman is advised by her mother-in-law to knock over a plant pot in her own home so that the soil that spills will distract visitors from noticing the beauty of the house itself.

Ancient Egyptians used kohl as a black rim around the eyes to protect against evil spirits entering the windows to the soul. A similar tradition is still practised today in parts of South Asia. Eye pendants to protect from malignant spiritual forces may have originated in Mesopotamia, and the Ancient Greeks had similar symbols to ward off evil.

In one counterintuitive practice, thought to have its roots in Jewish tradition, well-wishers say the opposite of what is meant, to avoid envy.

“I remember waiting for my daughter at a school pick-up and when I saw her, I said, 'Hello ugly,'” one Turkish-Cypriot woman said. “Her teacher heard and was horrified that I’d call my own daughter ugly. I then had to explain that in my culture we often say the opposite, as a way to detract from the evil eye.”

In some Bedouin communities, mothers keep their children unkempt for fear their beauty may invite ain.

In a sharp contrast to the spirit of the social media age, many Middle Eastern traditions encouraged possessors of wealth, happiness and beauty to avoid conspicuous displays of their good fortune. The sentiment is captured in a line written by Lebanese poet Kahlil Gibran: “Travel and tell no one, live a true love story and tell no one, live happily and tell no one, people ruin beautiful things."

'Bad spirits'

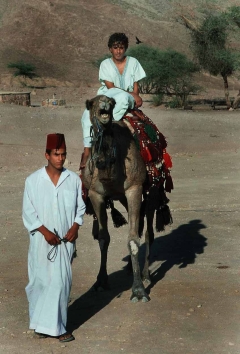

Belief in the evil eye and ways to protect against it have been around since the beginning of recorded history, at least as far back as the Sumerians, 5,000 years ago. A popular saying among the Bedouins reflects the significance of ain: "The evil eye can bring a man to his grave, and a camel to the cooking pot."

Professor Aref Abu-Rabia, an anthropologist from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, has studied the Bedouin community in the Negev desert, and says they have always regarded the evil eye as a very real “dangerous force” that has the power to impact lives.

Abu-Rabia writes: "A person who possesses an evil eye is said to have impure spirits that convey an intense will and the desire to cause harm, disorder and damage, whether by looking at the victim or by means of direct or indirect rites, such as prayers or curses."

The evil eye can be blamed for anything from a marriage failing to a child becoming sick, or to the loss of a job. Excessive drowsiness, yawning or a lack of concentration are also sometimes explained away as the effects of ain.

In Bedouin folklore there are three levels of the evil eye: someone who unwittingly praises something without making the correct blessings; someone who is aware of their envy but avoids saying anything; and the aradh, a person purposely seeking out an individual to cause harm through their bitter gaze.

The most vulnerable to the evil eye are said to be the healthy, beautiful and wealthy, as well as children and pregnant women.

The concept of evil eye can be found in the Abrahamic religions and the Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said: "The evil eye is real, and if anything were to overtake divine decree, it would be the evil eye."

Observant Jews often say kennahara, a contraction of the words kein eina hara, or "without an evil eye". And followers of Kabbalah, a mystical trend within Judaism, tie a red thread around their left wrist to ward off the eye.

Here, Middle East Eye summarises five symbols and traditions that are still in use today to protect people from ain.

1. Amulets

These are a common sight in many homes and can even be seen dangling from the rear-view mirror of cars, or worn around the neck or wrist as jewellery.

The blue glass beads, with a white spot and smaller black dot in the middle, are called nazar in Turkish, and are said to have been used for protection by peoples as diverse as the Assyrians, Phoenicians, Romans, Ottomans and Greeks.

The eye-shaped bead is said to deflect the unwanted negative gaze cast by others back onto the one who has the evil eye.

Another popular talisman is the Hand of Fatima, named after the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter, or the Hand of Miriam in Jewish tradition. It often has an eye at the centre of the palm to protect against misfortune and shield its owner from the powers of the evil eye.

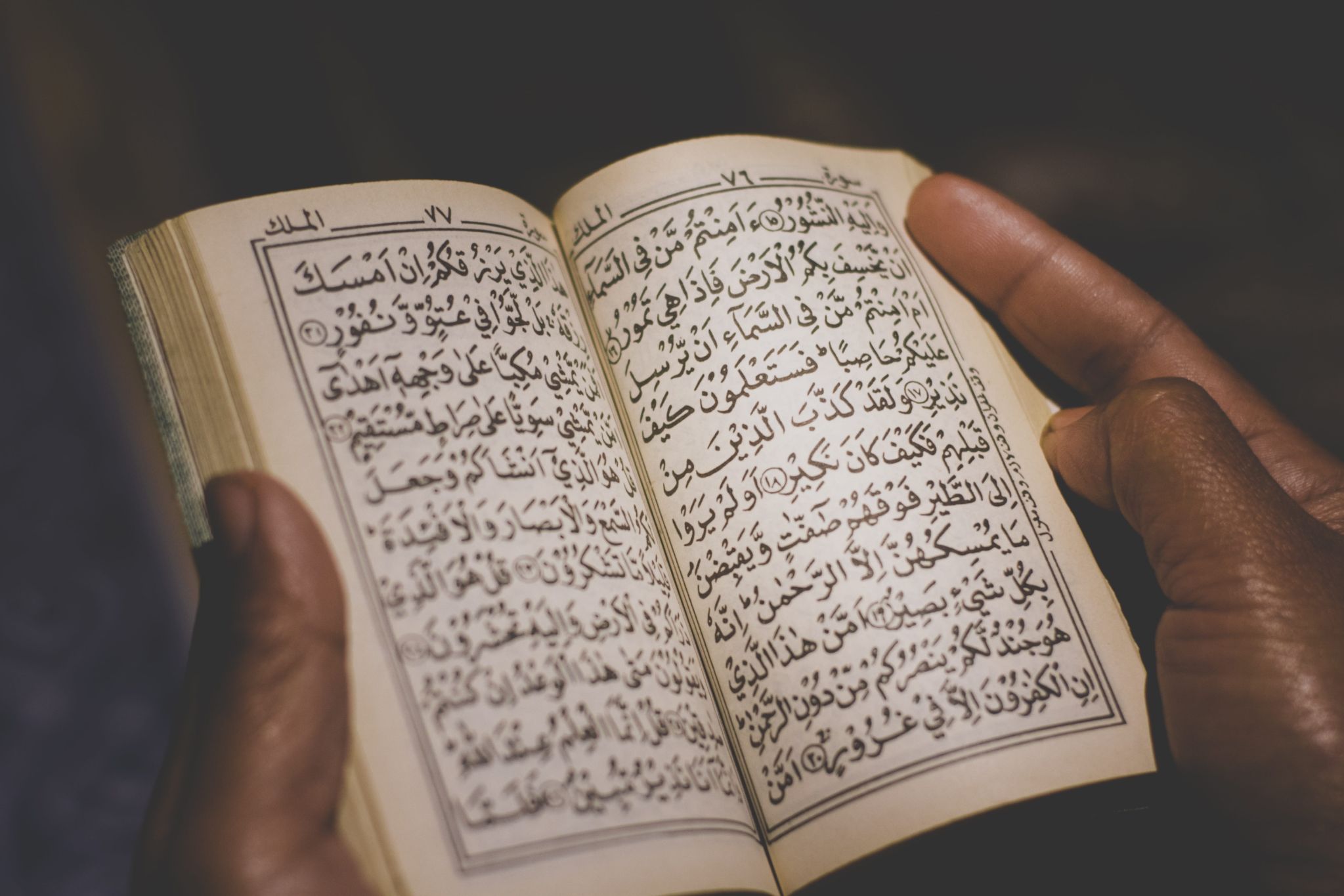

2. Quranic recitations

Despite the widespread popularity of amulets in the Islamic world, many Muslims believe they are not allowed in Islam and strongly oppose their use. They believe that only God can protect a person from evil spirits, and so their traditions against the evil eye are rooted in words of prayer.

There are a number of Quranic verses and surahs (chapters) that are commonly believed to be effective against forces associated with ain. The most common among these are a pair of short surahs that begin with the word Qul (the invocation "say" in Arabic). They are Surah al-Falaq (Daybreak) and Surah an-Nas (Mankind), which are collectively known as Al-Mu'awwidhateyn or "the verses of refuge".

There are other verses within the Quran that are believed to be effective against the evil eye, and most of these involve direct invocations of God's power to overcome evil.

Islamic tradition has many anecdotes about the effectiveness of using the Quran against bad spirits and envy. Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, a 14th-century Syrian Islamic jurist, wrote about a Bedouin who discovered the person who made his once lively camel unwell, simply through ain. On reciting some verses from the Quran, the Bedouin is said to have been able to heal his camel and out the perpetrator.

3. Burning incense

Burning incense to ward off bad spirits and forces is a practice common across the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia.

Bedouins burn agarwood or incense around the one who has been cursed, to clean the negative energy cast by the evil eye. In Egypt, black seed (habbat el barakah) or thyme are preferred.

In Iran, believers in the evil eye use esfand seed, which is also known as Syrian Rue. In Iranian homes the incense is heated up until the seeds pop, to protect against cheshm khordan, or being afflicted by the eye. The practice is thought to date back to when Zoroastrianism dominated Iran and is said to be effective in clearing away negative energy. Shopkeepers often burn it around their stores in the hope of better trade, and it’s also burnt to clean the energy in new homes.

4. Spitting, three times

A pretend spit, three times, with no saliva actually leaving the mouth, sounds a bit like "thu thu thu". This ritual seems to have been practised by many cultures, including the Greeks and the Romans, and the latter called the act despuere malum, which means to spit at evil.

Long practised by Jews, it’s seen as an easy way to protect from the eye, and goes hand in hand with prayers, including kinehore.

Among some Bedouins, healers don't hold back, and use their saliva to cure the afflicted from the tragedies of the evil eye - the belief being the saliva of a man will cure a man, and that of a woman will cure a woman.

5. Bottom scratch or pinch

Iranians do it, Lebanese Armenians do it, and so do Assyrians, although all have slightly different approaches and phrases that accompany the act.

Among Armenians the phrase char atchk is said while giving the backside a quick scratch to prevent a compliment turning into a curse.

Assyrians also have the same practice, but it’s a slight bottom pinch instead of a scratch, followed by the words theesa moocha and backed up with mashallah for good measure.

The theory is, the pain felt from the pinch should make the evil eye no longer envious of your success, as you are now in pain.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.