My End is My Beginning: A wild sci-fi ride at the end of the world

My End is My Beginning, the late long-time PEN International vice-president Moris Farhi’s swansong, is a paean to freedom of expression and vigilance in the face of authoritarianism, that makes compelling reading for these troubled times.

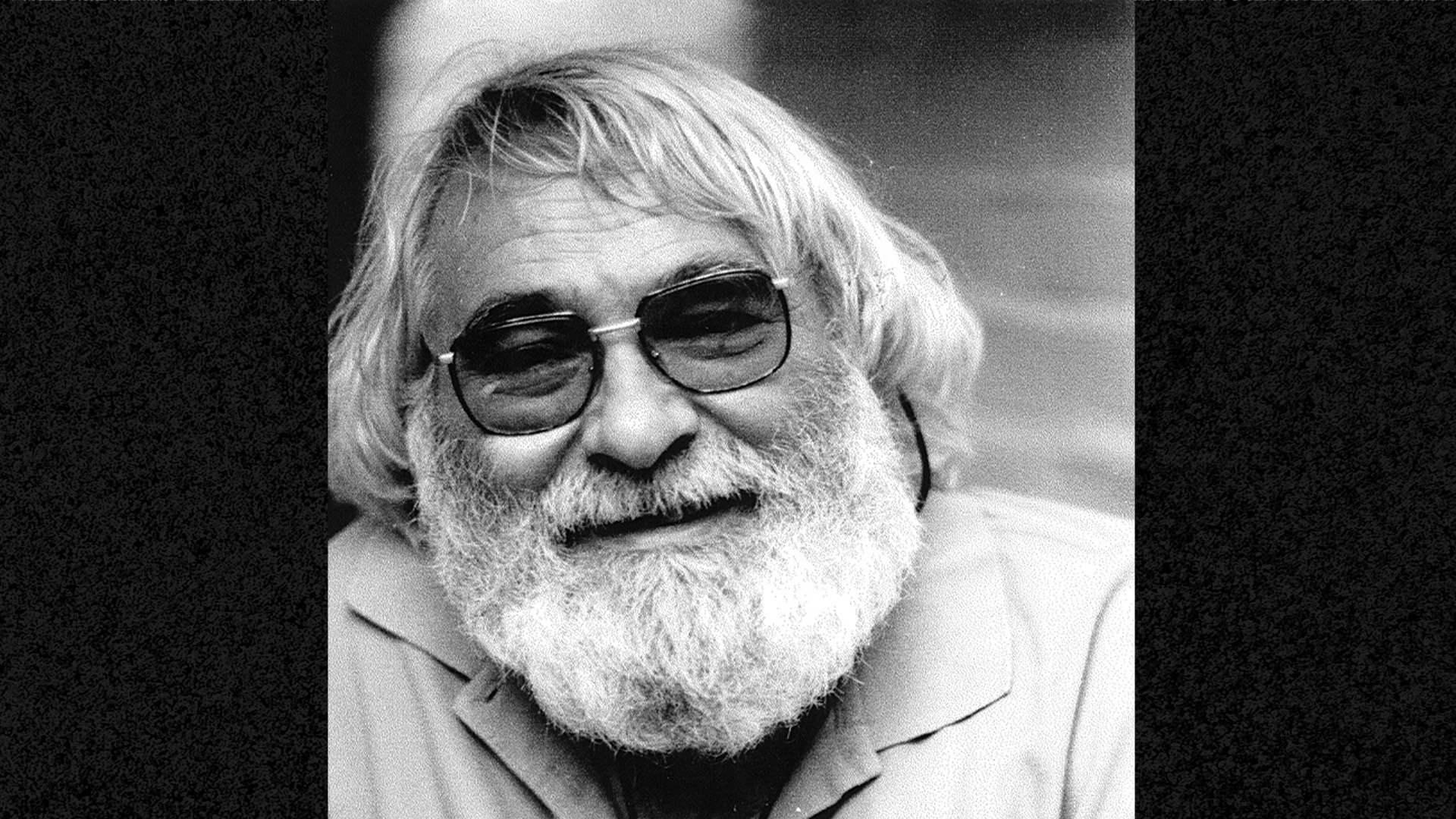

The award-winning Turkish born author, who died in 2019, was a larger than life, big-hearted man who especially championed persecuted writers and migrants, and his personality shines through in the central character of Oric, the writer-hero whose journaling keeps him sane in an insane world.

The imagined future world – like all great sci-fi – is in fact quite current, in these strange pandemic days. Fortuitously, my journey through Farhi’s book coincided with the death of my television, and his last literary testament to the highs and lows of being human became both a replacement for and an antidote to the awful state of current affairs.

In it Oric and his female soulmate Belkis are part of a league of do-gooding globe trotters (one-part PEN Internationalists, one-part Samaritans, one-part covert operatives practising radical secular humanism) called “dolphineros” who, when they die, transform into immortal leviathans. In fact, the author seems enamoured of oceanic references and anything connected to the sea evokes an imagined purity.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The pair are up against tyrannical “saviours” - autocratic leaders who use “big lies”, surveillance and repression to control the masses. The arch-villains are the Grand Mufti - a fantasia of various Islamist bad guys, leaning towards Iran’s supreme leader - and Numen, a dictator who could be Putin, Trump or some sort of evil hybrid of both.

The work begins on an apocalyptic note: “Today the sun’s axis shifted. Its marigold luminosity fell into thick Arctic darkness.”

A temporary union between Numen and the Grand Mufti is described by propagandists as ushering in a new age of enlightenment, while “many pundits intimate that this aspiration conceals a new dark age as its main agenda, namely the degradation of Numen’s subjects into lotus-eaters and the Grand Mufti’s into theoleptics.”

There seems to be an allusion here to a kind of dystopian version of the Imam Mahdi and even to Brexit as the enlightened “leviathans” sing the EU's adopted anthem, Beethoven’s Ode to Joy.

In a slightly pre-woke “right on” world that one could easily imagine taking shape at one of Farhi’s legendary dinner parties in the British seaside town of Hove, codes emerge for current-day “futurisms”. “Pinkies” are the new secret police and the likes of Rumi, Goya, Galileo, Neruda and Akhmatova are invoked as “ascended masters”.

When Belkis is killed by the Saviours' minions, Oric purges his survivor’s guilt by keeping up the good fight while dodging dangers around the world as a kind of superhero of secular liberalism and champion of borderless pluralism.

Bewildering pastiche

Born in Ankara in 1935 to a mother from Salonica, who later lost her extended family in the Holocaust, and a Bulgarian Turkish-born Sephardi father, Farhi moved to the UK at age 19 and graduated from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in 1956.

After a brief stint as an actor, he went on to a career as a screenwriter, poet and author who served as vice-President of PEN International – the worldwide association that champions freedom of expression and advocates for persecuted writers - from 2001 until his passing. His colourful life was dedicated to fighting injustice and helping others; the book often reads like autobiographical fantasy, with his family history merging with sci-fi dystopias.

It’s almost as if the TV news dropped acid and lay down with the Old Testament, and then set out on a honeymoon organised by Amnesty International and James Bond

But is it a book? A screenplay in waiting? Or a phantasmagorically long version of poet Allen Ginsberg’s hallucinatory epic Howl, time travelled to 2020?

It’s almost as if the TV news dropped acid and lay down with the Old Testament, and then set out on a honeymoon organised by Amnesty International and James Bond (the actor turned writer actually appeared in two 007 films – as a gypsy in 1963’s From Russia With Love and as a control room technician in 1967’s You Only Live Twice).

Some of the chapters could certainly be imagined as episodes of Doctor Who – the British sci-fi tv show that a young Farhi wrote for briefly in the 60s. Or even of Return of the Saint – the late 70s British television programme (a re-hash of the 1960s series called The Saint starring Roger Moore) that he also contributed to - about a mysterious, independently wealthy humanitarian who travelled the world helping strangers.

The chapters read like human rights travelogues – with details of scenery and food described alongside abuses - ranging from the plight of the Uyghurs in China to domestic workers in Saudi Arabia to rescuing activists from a repressive Honduran regime backed by drug lords.

One senses that the well-travelled author is keen to show both the joys and the dangers of this world, an admirable effort but one that often feels like a hard-hitting political documentary married to a travel show hosted by a secret agent - a bewilderingly beautiful pastiche.

Writer bias

While Farhi leaves no stone unturned in his lexicon of liberal causes, there is a certain bias evidenced throughout. While migrants are celebrated as downtrodden brothers, suicide bombers are “death worshippers” – and Israel/Palestine receives but a brief mention.

The evils of sharia law are extolled, but there are no rescue missions to liberate Palestinian activists from Israeli dungeons. In one scene, the political union between Numen and the Grand Mufti is described as a kind of conspiracy between extremist Christians and Muslims to wipe out the Jews - rather the opposite of current Christian-Zionist-Trumpian doctrine.

“The Grand Mufti affirms, through his interpreter, that he’s ready for Armageddon, ready to emerge as al Mahdi, the twelfth Imam and Prophet’s successor. Thereafter both he and Numen will syncretise their orthodoxies into the true religion humankind craves. To achieve this they will first extirpate the apostate creed, Judaism, that has poisoned humanity…”

Although it’s hard to tell exactly which country – or countries – Numen rules; in some chapters it seems to be Israel/Palestine. In one, Farhi recounts a scene at a train station that could be Tel Aviv, where soldiers return from fighting “terrorists”.

“The terrorists,” he writes, “are the large indigenous minority in our eastern provinces. Numen condemned them to ethnic cleansing for campaigning for an autonomous canton…. where they can speak their own language and pursue their own culture. To date the conflict has claimed thousands of lives on both sides. Lately Numen has intensified the hostilities.”

In the same chapter he writes of liberals shipped to labour camps and the “mothers of the disappeared.” Could this be code for the secular Zionist dream/nightmare? Or could he be alluding to Putin’s Russian and Chechen rebels?

While many chapters are extremely specific – like the one called “Pax Mundi” about a kind of “Up with People” style cross-cultural musical jubilee in a right-wing Hungary where the Roma and migrants are persecuted (just barely prescient as Orban virtually declares himself supreme leader), the exact location of Numen’s land is rather vague, perhaps a deliberate technique that indicates the global pandemic of state repression.

One chapter recounts an odd kind of “speaker’s corner” (which perhaps suggests, as in Orwell’s 1984, today’s UK) controlled by secret police who scare away true dissidents but allow the likes of jihadists, Christian evangelicals and Messianic Jews to offer their strange opium to the masses. While Farhi writes of Numen’s “yes-men” inhabiting a suburban landscape of chlorinated pools, BBQs and fresh cut grass, he also refers to stopping an American “tourist” in a city of seven hills. Could that city be Jerusalem, Rome, Paris, Lisbon, even an independent New York? That’s left to the reader’s imagination.

The accompanying story of Amado, a poet who dies after being tortured, is genuinely moving and seems inspired by one of Farhi’s real-life Pen International missions. The character somehow recalls the tortured poet in Fellini’s Satyricon.

And the cinematic references continue with the character of a disillusioned police inspector who knows too much, banished to a prison-like “palace” full of drugged dissidents, recalling Charlton Heston’s famous character, NYPD detective Frank Thorn, in another imagined dystopian future world. I half expected him to yell out "Soylent Green is people!"

The Plague, as musical

While Farhi gets full points for enthusiasm and zeal when it comes to championing human rights, he lets down the side when it comes to fully drawn-out women characters. Even as Oric fights for their cause, they are mostly victims to be rescued by white saviours, or eco-feminist sex goddesses ready to pleasure the protagonist in the name of “spiritual” union.

Existential purists may find this book a wild ride sci-fi musical version of Camus’ La Peste

Intriguingly, for all his Islamist villains, Farhi does take pains to emphasise the difference between misguided jihadism and true Islam. In one weird chapter called “Anwar”, he recounts the tale of a group of Sufi youth in Dagestan, captured by an ISIS-like group called the “Black Standard”.

Forced to sully their pure Sufi ways by a band of criminals who coerce them to watch porn, drug themselves and glorify violence so they can become cannon fodder in Syria, the youth decide to escape their fate via group overdose on heroin. All perish but one named Anwar, who, still keen on purifying himself, swims to Kazakhstan. When his drowned body is found, it appears “translucent”.

While existential purists may find this book a wild ride sci-fi musical version of Camus’ La Peste – where one brings along dancing shoes as well as discerning reading glasses - the work was perhaps the author’s personal way of practising “tikkun olam”, a concept which in Hebrew corresponds to repairing the world - albeit through a Jewish humanist lens.

My End is My Beginning, by Moris Farhi, is published by Saqi Books

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.