Mukarram Jah: An Indian prince and claimant to the Islamic caliphate

On Saturday 14 January 2023, Prince Mukarram Jah, the titular nizam of Hyderabad, died in Istanbul at the age of 89.

Belonging to a dynasty that once ruled a princely state the size of Italy in southern India, Jah was also the grandson of Abdulmecid II, the last Ottoman caliph and the last person to ever hold the title, nearly a century ago.

Few people, especially outside of the Indian subcontinent, are aware that the Harrow and Cambridge-educated Jah was nominated by Abdulmecid to be the caliph, a title designated to successors of the Prophet Muhammad.

Now that Mukarram Jah has died, his heir, Prince Azmet Jah, has a claim to the title; one first held by the prophet's close companion Abu Bakr and which traditionally entailed political and spiritual leadership of the Muslim community.

What follows is the little-known story of how the scions of an Indian princely family hold claim to one of Sunni Islam's most revered institutions.

Next year marks a hundred years since the fledgling Republic of Turkey abolished the caliphate. It was a moment of global significance: the caliphate had endured for 1,300 years after the Prophet Muhammad's death and could claim the loyalty of tens of millions of Muslims globally.

The title had never been undisputed, but the end of the caliphate in 1924 left the Muslim world, much of it under European colonial rule, without an authoritative religious leader.

The move was part of the nation-building project pursued by the newly-formed secular government of Turkey. In November 1922 its Grand National Assembly abolished the Ottoman sultanate, deposing Sultan Mehmet VI.

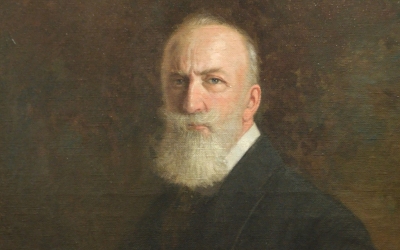

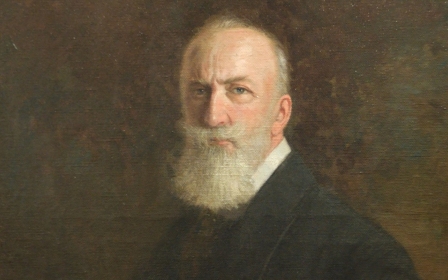

Abdulmecid, a talented painter-musician-prince who had never been involved in the running of the empire, was installed as a puppet figure and became Caliph Abdulmecid II, even as a campaign to abolish the caliphate developed.

The Indian connection

In India, the Caliphate Movement raised a clamour in support of Abdulmecid, which concerned British authorities opposed to any pan-Islamic institution that could transcend states and empires.

Even more worrying for colonial officials was the fact that the Caliphate Movement became a mass mobilisation of Indians across religious divides.

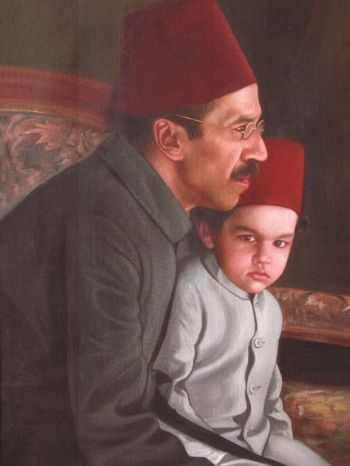

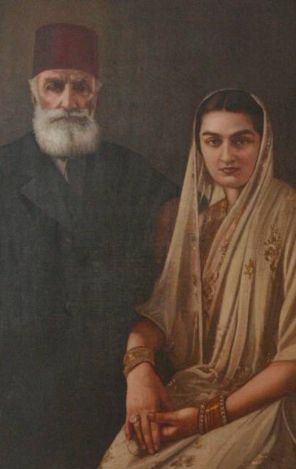

father, Azam Jah (National Archives)

Mahatma Gandhi and other prominent anti-colonialists seized the day and joined in; the movement was billed as a show of Hindu-Muslim unity against Britain. Its leader was Maulana Shaukat Ali, an Anglicised former civil servant who had transformed himself into a leading figure in the struggle for freedom.

In November 1923, the movement sent a letter to Ismet Pasha, the prime minister of Turkey, urging him to give the caliphate its due prominence as a focal point of solidarity for the world’s Muslims.

The Turkish government decried attempted foreign intervention and used the Caliphate Movement, as well as claims of a pro-Ottoman monarchist plot in Turkey, as a pretext for the abolition of the caliphate in March 1924.

The Ottoman royal family were put on the Orient Express and ended up in Switzerland, where they lived in "absolute penury", according to the Red Crescent Society. The Daily Mail reported that the "ex-caliph spends his days in prayer, painting and composing music".

Monetary assistance came from an unexpected place: Hyderabad, an Indian princely state under indirect British control and governed by the Muslim Asaf Jah dynasty.

Hyderabad’s ruler, the seventh nizam, was Osman Ali Khan, the world’s richest man, who employed 12,000 palace servants, used a £50m diamond as a paperweight and set up his own whisky distillery.

Under the watchful eye of the British Empire, Hyderabad existed as an almost implausible relic of a bygone era, a last vestige of the Mughal past.

The extravagance of elite life there was legendary. Hyderabad’s palaces were drenched with opulence and an old-fashioned Indo-Islamic grandeur.

The nizam, himself a talented poet, procured magnificent Mughal miniatures and antique illuminated copies of the Quran. Qawwali masters frequented the royal court, performing renditions of mystical poetry to the beat of the drum and the gurgle of the waterpipe.

The nizam hosted grand dinners at which “the men were elegant in black sherwanis or gorgeous in gold brocade, the ladies wore saris of sapphire or flame-colour or starlit blue… the plates were covered with Persian pilaus, Mughal kebabs, Indian curries, French salads - dishes to suit every taste,” according to a British eyewitness.

At garden parties a 60-piece string orchestra played waltzes and foxtrots. The nizam had his own jazz band, too, which he led in performing his favourite song, I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.

His reign saw relatively good governance (compared with British India), and the nizam was enormously popular with his mainly Hindu subjects. He funded Hindu festivals and all sorts of mosques, Sufi shrines, temples, churches and gurdwaras. “Muslims and Hindus are my two eyes,” he declared.

The nizam felt guilty for not supporting the Ottoman Empire before its collapse and wanted to help the former caliph. He proposed giving Abdulmecid and his household £300 a month.

The Ottoman-Asaf Jah union

During their exile, Abdulmecid and the rest of the Ottoman clan ended up in a 19th-century villa on the French Riviera.

The former caliph was often sighted on the beach, “attired in swimming trunks only and carrying a large parasol”.

Meanwhile, Maulana Shaukat Ali, who had led the Caliphate Movement, was working with Marmaduke Pickthall, an English scholar of Islam employed by the nizam to translate the Qur’an into English, on another ambitious scheme.

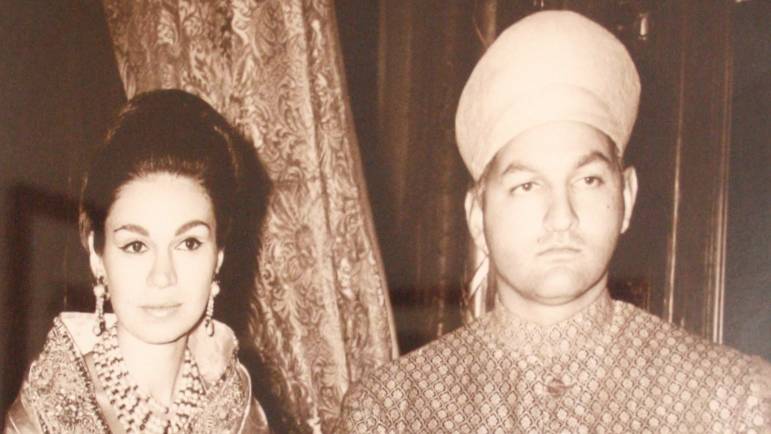

Durrushehvar in Chowmahalla Palace

(Creative Commons/Kandukuru Nagarjun)

They proposed that the nizam’s son, Azam Jah, marry the former caliph’s daughter, Princess Durrushehvar, and a younger son of the nizam, Moazzam Jah, marry her cousin Niloufer.

The nizam and Abdulmecid agreed to the plan, and in late 1931 Azam and Moazzam Jah arrived at the Negresco, a luxurious hotel in the French city of Nice, booking out two entire floors for their entourage.

The weddings were held at the nearby Palais Carabacel, and the nizam sent Abdulmecid a message asserting that “an alliance has been established between the two ancient and historic dynasties which, it is hoped, has prospects of a bright future”.

The colonial authorities were alarmed: Terence Keyes, who had the role of British resident in Hyderabad, wrote to the viceroy of “an open revival of the scheme” to bring the caliphate to Hyderabad. The Turkish embassy in Britain condemned the “Caliphate intrigue” it saw in the marriages.

Maulana Shaukat Ali, whose plan had worked, headed to Palestine that December to attend the World Islamic Congress, which he had organised with the grand mufti of Jerusalem. Ali aimed to mobilise support for what British spies reported was his “scheme for a Pan-Islamic Federation”.

The meeting was a failure, with many attendees opposing the Ottoman claim to Muslim leadership. There was, moreover, no Muslim power that was strong enough to challenge colonial designs.

The recently married couples, meanwhile, were settling into their new lives. Princess Durrushehvar took up residence in the Bella Vista, an Indo-European palace in Hyderabad, learnt to speak fluent Urdu, patronised hospitals and set up a junior college for girls.

Her cousin Niloufer, who also engaged in charitable efforts, became a fashion icon, known for merging European and Indian styles in her clothing. The two young women were celebrities, stealing the show at parties frequented by Hyderabad’s glamorous elite.

Then, in late 1933, came the moment everyone had been waiting for: Princess Durrushehvar gave birth to a son, Prince Mukarram Jah. The nizam chose the baby to be his heir, bypassing his son, who was uninterested in the role.

Pretender to the caliphate

Prince Mukarram Jah was positioned to become leader of the world’s Muslims. Historian John Zubrzycki writes in The Last Nizam that British officials were shocked when they discovered in Abdulmecid’s will (the final Ottoman caliph died in Paris in 1944) that he had nominated Jah - his grandson - to be his heir and the next pretender to the caliphate.

But this, of course, would never come to pass. Hyderabad was under colonial control, and India’s transition to independence was being shaped by democratic politicians, not princes.

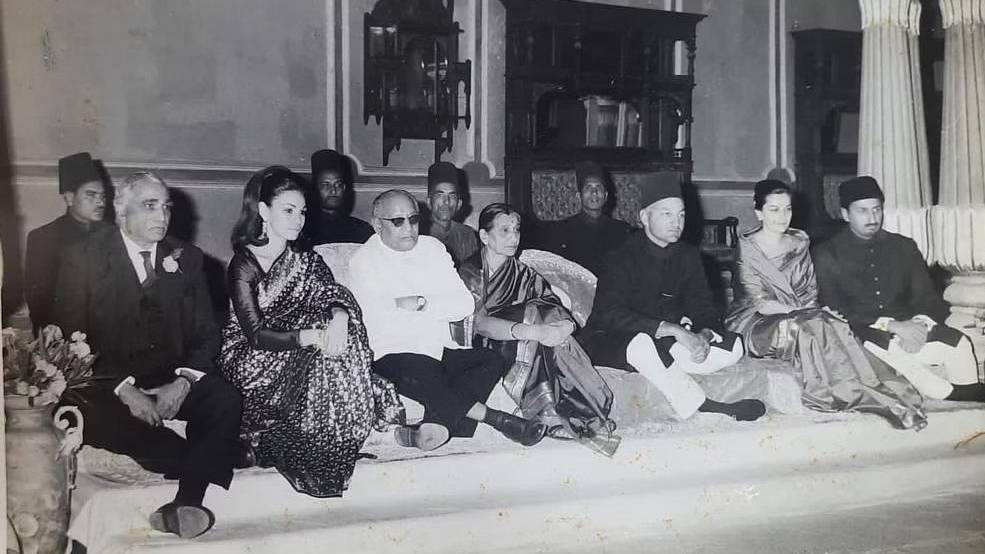

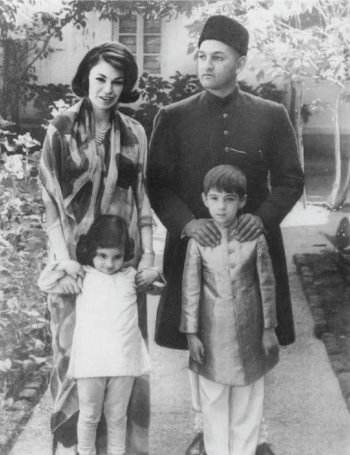

(front right), seen here in this family photo

(National Archives)

The mastermind behind the Ottoman alliance with Hyderabad, Maulana Shaukat Ali, continued to be a major player in Indian politics. In 1936 he joined the Muslim League and became a close ally of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the glamorous lawyer-politician styling himself as leader of India’s Muslims.

In 1940 the Muslim League declared its support for an independent Muslim state: Pakistan.

By 1947, attempts to secure a compromise - an Indian Federation with autonomy for Muslim-majority provinces - had failed. As the British prepared to leave with partition on the horizon, among Hyderabad’s elite the parties raged on, more magnificent and exuberant than ever, as a defiant final flowering of the old Indo-Islamic culture.

The nizam wished for Hyderabad to be sovereign and autonomous, envisaging that his heir Mukarram Jah would be a great and powerful leader, caliph of the world’s Muslims.

But the new government of independent India refused to accept the nizam controlling a giant state in the middle of Indian territory.

Jinnah, who led the newly created Pakistan, had a rocky relationship with the nizam. In 1946 their meeting in Hyderabad to discuss the state’s future had failed miserably when Jinnah sauntered into the meeting smoking a cigar, before casually sitting in front of the nizam with his legs outstretched (“Do you know who I am?” the nizam shouted, causing Jinnah to hurriedly throw his cigar away).

Despite this, in the month before partition, Jinnah advised the nizam not to submit to India’s demands, and warned the British viceroy hyperbolically that if the Indian government “attempted to exert any pressure on Hyderabad, every Muslim throughout the whole of India, yes, all the hundred million Muslims, would rise as one man to defend the oldest Muslim dynasty in India”. This posturing emboldened Hyderabad’s government.

But by autumn 1948 the Indian army had encircled Hyderabad. Jinnah died on 11 September, triggering chaos in Pakistan and making any military intervention on Hyderabad’s behalf impossible. Less than two days later the Indian army invaded the state; it was incorporated into India and is now called Telangana, with the city of Hyderabad its capital.

The outcome was devastating. Independent reports say that at least tens of thousands of Muslims died in the invasion, and Indian army officers have been accused of committing war crimes. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was aghast to hear that so many Muslims were killed “as to stagger the imagination”. Hyderabad would never be the same again.

Life after independence

As for Princess Durrushehvar, she lived in London until her death in 2006 at the age of 92. Her son Mukarram Jah, the nizam’s heir, attended Harrow and then Cambridge, like his father had done. In the mid-1950s, while a student, he and his mother ran into Earl Mountbatten, who had been the last viceroy of India, at a function. All the Earl could manage to say to Princess Durrushehvar was “Sorry, ma’am.”

When the nizam died in 1967 and Mukarram Jah succeeded him, he was in no position to adopt the title of caliph. The new nizam had no power and a legally disputed inheritance claimed by thousands of people. In 1974 the Indian government abolished his title and subjected him to new taxes and land acts. In the end, most of the dynasty’s property was sold off.

This represented the loss of privilege for a wealthy elite. But it meant the crumbling, as well, of the last vestige of a sophisticated and tolerant Indo-Islamic culture whose world view and beauty were important not just to a small nobility but a whole people.

As the titular nizam, Mukarram Jah defied all expectations by moving to a sheep farm in Australia in 1973, where he enjoyed driving bulldozers.

Eventually he took up residence in a small apartment in Istanbul, the former heart of the Ottoman Empire, where he died this month. But the nizam always maintained connections with Hyderabad through his charitable initiatives, and it is in Hyderabad that he has been buried.

His eldest son, Prince Azmet Jah, is a British filmmaker who has worked with Hollywood directors including Steven Spielberg and Richard Attenborough.

He will succeed his father as the next titular nizam of Hyderabad. What most people have no idea about, however, is that Jah also has a strong claim to the title of caliph, the result of that remarkable alliance established between the Ottomans and one of the world’s richest Muslim families almost a century ago.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.