On Muslim Democracy: The evolution of Rached Ghannouchi’s political and theological ideas

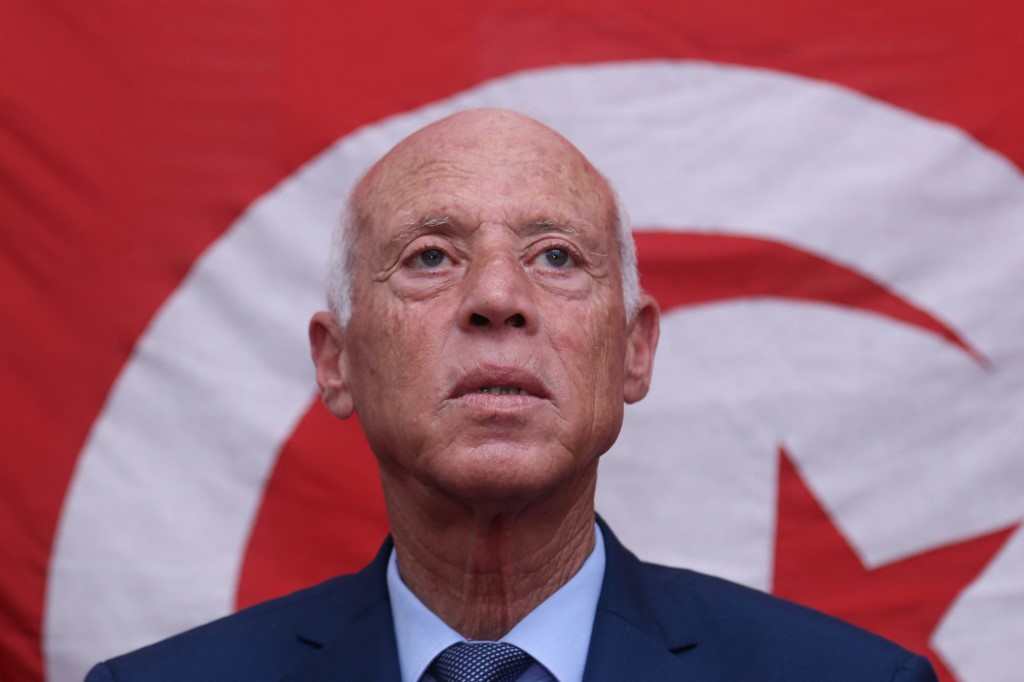

Rached Ghannouchi was the standard bearer of a political Islam that had made peace with democracy, but in the 2010s he gradually transitioned to a second phase, which is reflected in his most recent publication, On Muslim Democracy.

Even in the earlier phase of his thinking and activism, the Tunisian Islamic scholar’s moderate brand of Islamism was influential in many parts of the world.

Shaykh Ghannouchi, as he was commonly called, co-founded a political party in Tunisia based on Islamic principles in the 1970s. Initially called The Islamic Tendency Movement, it later became Ennahda.

The opposition of its members to the authoritarianism of Habib Bourguiba’s regime and their successful organising on university campuses led to the imprisonment of Ghannouchi and other Ennahda leaders in 1981.

Two long prison sentences that decade allowed him to write most of what later became his magnum opus, Public Freedoms in the Islamic State.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Ghannouchi was then exiled in 1989 and spent most of that time in the UK, becoming a leader within a pluralistic stream of political Islam.

In a nutshell, he saw the state as founded on Islamic law but politics revolving around free elections, separation of powers, and citizens with equal rights, whatever their religious background.

His political system also relies both on Muslim citizens who remain vigilant in upholding Islamic values and rituals, and on a constitutional court with Islamic jurists who have the authority to strike down laws that contravene the spirit and letter of sacred texts and established Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh).

A shift in thought

That first phase of Ghannouchi’s political theory and practice already set him apart from the Muslim Brotherhood and other politically Islamic movements in that he recognised all political parties as legitimate, whether secular or religious.

Furthermore, Ghannouchi believed that when they could, all parties should work together for the greater good of the nation.

Yet even before the December 2010 revolution in Tunisia, which overthrew the dictator Ben Ali and opened the way for Ghannouchi’s return to his homeland at the helm of Ennahda, his thinking had evolved.

It is surely a crime that at age 82 Rached Ghannouchi is once again in prison for speaking out for justice and freedom

And it continued to do so in the push and pull of Ennahda’s partnership with other parties, leading up to the writing of the new constitution officially launched in 2014.

A telltale sign that Ennahda was evolving is that, despite being Tunisia’s leading political party, it signed on to a new constitution that made no mention of Sharia.

This brings us to the present project, On Muslim Democracy. Historically, the watershed moment came during Ennahda’s 10th Congress in 2016, when Ghannouchi in his opening speech declared that Tunisia no longer needed political Islam.

What he meant was that Tunisia, as an overwhelmingly Muslim nation, needed a Muslim party that could cooperate with other political formations to meet the nation’s economic, social, and security challenges while modeling through their outreach, the Islamic values and norms they saw as necessary for the wider political project.

But this also meant that Ennahda was a party like all the others, not a third column infiltrating the religious establishment to transform the nation into an Islamic republic.

To make this abundantly clear, Ghannouchi declared in his speech that no party member could hold an official position in a mosque. Religion and state are two different things and should not be mixed, he argued.

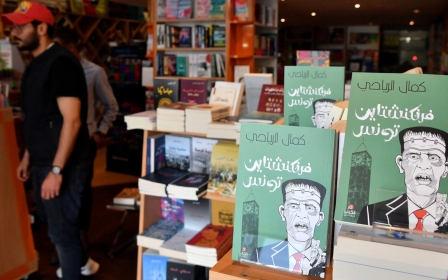

This book, then, captures the transition of Ghannouchi’s political theory and practice from one phase to the other.

It does so, thanks to the close collaboration between political scientist and Islamicist Andrew March and Rached Ghannouchi.

March had long studied and written about modern Islamic political theory. He had also focused his attention on Ghannouchi’s writings and visited him several times in Tunisia.

This volume, nicely articulated in three parts, is therefore an invaluable resource for understanding the legacy of one of the most influential Muslim political thinkers of our time.

Securing alliances

March’s introductory essay sets the stage for the ten articles he translated into English for the first time and then for the roughly ninety pages of dialogue between Ghannouchi and himself.

As someone intimately acquainted with Ghannouchi’s Public Freedoms in the Islamic State, I still learned a great deal from March’s framing of the issues in his essay and subsequently in the questions he posed to Ghannouchi in their conversation.

The latter’s political theory, and political theology, are complex and multilayered, and March’s probing of Ghannouchi’s thought from various angles offers us a fuller picture of what “Muslim politics" represents in Ghannouchi’s mind. These dialogues took place in 2021 and 2022.

I begin with a few remarks about the opening essay. Besides the thumbnail sketch of Ghannouchi’s political trajectory (the dialogues go into much greater detail), March offers a trenchant analysis of Tunisia’s politics between 2011 and 2021 and he helpfully elucidates two paradoxes.

The first is that even though Ennahda remained the most popular and effective Tunisian political party throughout this period, it was also the most hated and distrusted by a large segment of the population.

And this, despite Ennahda’s bending over backward to accommodate the more secular parties on several issues, and despite Ghannouchi’s close working relationship (2014-2019) with the president and founder of the largest secular party, Beji Caid Essebsi.

True, the extreme polarisation of Tunisian politics was certainly not helped by the secularists tarring Ennahda at every turn as religious radicals who would easily turn to violence if circumstances permitted.

The second paradox has to do with the central role played by “an active, engaged, and deliberative populus” in Ghannouchi’s political theory.

A virtuous Muslim citizenry was in his mind at the heart of a well-functioning Muslim democracy. Yet in practice, to keep a profoundly divided nation from falling apart, Ghannouchi invested great effort again and again to broker deals among the political elites.

This coalition building became even more crucial after the newly elected president, Kais Saied, dissolved parliament in July 2021.

Then, a year later, he rammed through a referendum on significantly widening his powers (with only 30.5 percent turnout).

This coup could never have succeeded but for the polarised and ineffectual policies that had made a bad economic situation much worse. But over time the general populace began to back a growing anti-coup movement, thanks to Ghannouchi reaching out to several other smaller parties.

Islamic democracy and Muslim democracy

Ghannouchi himself was initially spared as the number of political prisoners was soaring, but in April 2023, he too was imprisoned, and he remains so today.

March’s essay is valuable in explaining the theory of "public freedoms". I found his argument in the section “Perfectionism” both an original and convincing analysis.

This is about Ghannouchi’s philosophical (or theological) anthropology, which starts with God’s empowerment of humanity as his “caliphs,” vicegerents, or deputies, both collectively and individually.

But in the next section, March highlights the inherent tension between an Islamic democracy, in which the people hold a delegated sovereignty, and an Islamic democracy, in which the government is delegated by the electorate to enforce Sharia norms and thereby promote the people’s welfare.

This theme of “tension between the ideal theory of an Islamic democracy and the theory of pluralist, liberal democracy” runs throughout the book, but especially in the dialogues section.

Most of the ten translated articles and pamphlets were written before the Jasmine Revolution, but, March argues, they already were pointing to the concept of a “Muslim democracy".

Some elements of the previous emphasis on moral perfectionism remain, like the idea of freedom being about “self-mastery and moral perfectionism”.

The crucial addition is that freedom itself takes a front seat in his political theory; freedom of the individual from government interference, and freedom within civil society to oppose an authoritarian ruler.

Also in these writings, and especially in the post-revolutionary ones, the so-called “Medina Constitution” or the Sahifa, becomes the main argument for a truly pluralist polity.

Under the Prophet’s leadership, Jews, pagans, Muslims, and tribes, to a certain extent, all lived as free citizens under one ruler. Diversity was good and freedom was its hallmark.

In at least two of his essays, human rights take centre stage. Here too we see a shift in his previous Islamist thinking. There had been, after all, two international “Islamic” declarations of human rights in the 1980s and 1990s.

Now the theology of the human caliphate affirms its applicability to all human beings, and not just to Muslims, and he sees the contemporary conception of universal human rights affirming the “negative” freedom of any Muslim.

That includes choosing to discharge the obligations of their faith through the shahada declaration and the observance of the other rituals.

March ends his essay with an evaluation of Muslim democracy. He urges his readers to make up their own minds upon reading this book: is the turn to Muslim democracy “an anti-ideology of political necessity”? Or is it better seen as a rethinking of Islam in light of the modern concepts of democracy and human rights?

A third option, seen as the most favourable, suggests a blend of both ideological and religious diversity. It supports collaboration with parties holding different worldviews but acknowledges that, over time, political differences may lead to a party with a majority view, like a Muslim party in a Muslim-majority nation, gaining influence and implementing its policies through democratic processes.

‘Dialogues’

That said, that last option falls far short of establishing an “Islamic republic". How does Ghannouchi feel about that?

With that question in mind, the last section (“dialogues”) is fascinating. For one thing, you get a fine-grain view of Ghannouchi and Ennahda’s actual political experience over four decades.

But even more important for this book is how March pushes Ghannouchi to clarify his thinking in those areas of tension.

In the section, “Democracy, Sovereignty and Morality,” March wants Ghannouchi to explain his main objections to the Western conception of democracy and the role of Islam in his own view of democracy.

With questions coming from several angles, Ghannouchi, who tends to be optimistic regarding the virtuous potential of a Muslim citizenry, ends up saying: “There is no perfect system and the world we live in is not an abode for establishing an ideal society."

One has to keep striving to strengthen a people’s spiritual and moral fiber through educational and cultural reform while reminding oneself that “mankind possesses many evils".

The second area of tension that struck me in Ghannouchi’s political theory is between the Prophetic tradition (hadith) that says that Muslims will never agree on wrongdoing (or “error”) and the fact that Muslims can interpret the sacred texts quite differently, or choose to ignore them when it’s convenient.

This applies, especially in the case of Tunisia, a relatively homogenous nation, to the idea of pluralism and religious freedom.

Ghannouchi has long debunked in his writings the traditional Islamic view of the death penalty for apostasy. Here he talks about making it easy for people to practice their Muslim faith but adds that “the path toward non-Islam should be possible but not easy".

He had already explained that Sharia is less about traditional jurisprudence than it is about the ethical norms of freedom and justice.

Thus, Muslims can freely choose to leave Islam, but in that case, they should run into some obstacles. What this might look like in practice he does not say. But the reader cannot miss the tension here.

Rached Ghannouchi is a brilliant political thinker and theologian and Andrew March has afforded him the opportunity to demonstrate that brilliance in these pages.

And now is the right time to read this book and pass it along. It is surely a crime that at age 82 Rached Ghannouchi is once again in prison for speaking out for justice and freedom.

On Muslim Democracy: Essays and Dialogues by Rached Ghannouchi and Andrew March is published by Oxford University Press

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.