From Nablus to Naples: How murals in Italy tell the story of Palestinian resistance

In an alley of Naples' historic centre, there is a mural depicting two soldiers in military uniforms and helmets climbing a ladder leading to the window of an elderly lady. The woman drives them away with a bucket of water. Instead of Naples's customary sight of clothes drying outside the windows, a Palestinian flag hangs on the washing line.

The image is the work of photographer Eduardo Castaldo who, in his free time, uses street art in this southern Italian city to raise awareness about Palestine.

The inspiration for this artwork came from a picture he took in the West Bank.

“This image left an impression on me, as these two soldiers seemed like characters from the Metal Gear Solid video game,” Castaldo tells MEE.

In another alley, a mural depicts the faces of Palestinians Castaldo encountered at the Israeli checkpoint 300, their expressions trapped behind prison-like bars.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Over the years, a special connection between the Italian city of Naples and Palestinian cities has blossomed, with solidarity in Naples depicted through resistance art, cultural organisations and advocacy for Palestinian rights.

Youth activism

Castaldo's work throughout Naples has gained worldwide attention thanks to social media.

He depicts the resilience of the people he has encountered, touching upon the Palestinian cause, the Egyptian revolution and the war in Ukraine.

Hailing from the suburbs of Naples, at 18 he moved to its historical centre, and his passion for Palestine took root during his time at the city's University Orientale, the oldest school of Oriental Studies in Europe.

There he connected with the local Palestinian community, who arrived in the 1970s as students. They played a significant role in raising awareness about their homeland within academic circles, helping to strengthen ties between Naples and Palestine.

“Although I did not know many Palestinians then, their influence was palpable and left an impression on me,” he says.

Around the same time, he discovered photography. His first assignment was in Naples in 2006, to cover the waste emergency before it gained widespread attention.

Capturing suffering

In 2007, Castaldo made a life-changing decision to move to the Palestinian West Bank city of Ramallah.

Later, he would also move to Cairo, to cover revolutionary and post-revolutionary events, which earned him widespread acclaim, including a World Press Photo Award in 2012.

In 2009 he also witnessed Operation Cast Lead, a three-week Israeli military offensive against Gaza that resulted in the destruction of infrastructure and the loss of around 1,400 Palestinian lives.

'I often questioned whether I had the right to document people's suffering through my photos'

- Eduardo Castaldo, photographer

As he delved deeper into his photojournalistic role, doubts started to creep in regarding the dynamics of his work.

"On one hand, I felt flattered, earned money and had the opportunity to work; but at the same time I often questioned whether I had the right to document people's suffering through my photos," Castaldo says.

“For example, I took a picture of a woman in Gaza amid the ruins of her home, along with her husband and children, in the aftermath of bombings. Or in Egypt, people allowed themselves to be photographed, they wanted to shout certain things and they trusted me to give voice to them.

“I felt unsure about using those photos within the realm of newspapers."

According to Castaldo, the media industry held the power to interpret his photos as they saw fit: “Whether they use softer or harsher words, they always manipulate the narrative.”

Photography to raise awareness

A major turning point in Castaldo’s life came in 2015 when a colleague, Luciano Ferrara, invited him to exhibit his work in the heart of Naples.

"The space was unique, filled with antiquities and personal belongings, different from traditional gallery settings," Castaldo said.

Showcasing his photos, which he had accumulated over eight years, felt liberating and showed Castaldo that he could use his work to raise awareness on issues that mattered to him.

In 2021 he decided to make public the photos he took at an Israeli military base in 2009, during a celebration for soldiers’ families.

Describing one of the photos on Instagram, where he shares his work, he adds context to what he witnessed and what is shown in the photo.

"Dozens of proud [Israeli] parents were happily showing their kids how to load grenade launchers and machine guns. Smiling soldiers were organising games and challenges in which nine-year-old children had to quickly mount rifles and shoot imaginary Arabs.

'I wandered the whole day taking pictures with a smile on my face and death in my heart'

- Eduardo Castaldo, photographer

"The amount of violence I witnessed was unbearable. I wandered the whole day taking pictures with a smile on my face and death in my heart."

Castaldo only shared his work from Palestine 12 years after taking the photos, driven by the realisation that those children of 2009 "had grown into soldiers accountable for the deaths of Palestinians".

To safeguard their identities, he replaced the children’s faces and flesh with flowery fabric, symbolically shielding them from who they had become.

However, sharing his work allowed him to see the powerful potential of his images, and how making them public could be a tool to raise awareness of the plight of Palestinians.

Discussion through art

Castaldo’s work has travelled beyond Naples, and sparked discussions in other countries across Europe.

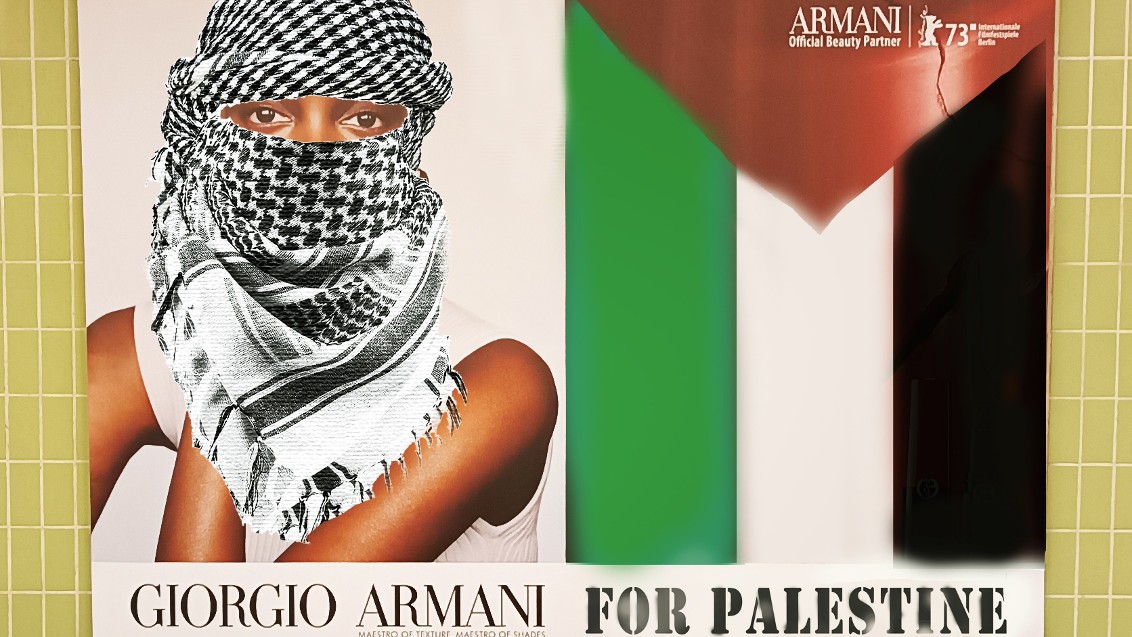

During a visit to Germany he digitally transformed an Armani advertisement for lipstick, covering the model in a black and white keffiyeh. The chequered scarf, which has become a symbol of Palestinian resistance, was also accompanied with the words "Giorgio Armani for Palestine".

In a playful manner, Castaldo claimed to have started a collaboration with haute couture brands.

Although many viewers mistook it for a real mural, for Castaldo the success of this digital artwork lay in its ability to initiate discussions, regardless of its authenticity in a physical sense.

Castaldo’s work is not the only example of art supporting the Palestinian cause in Italy.

Renowned Neapolitan-Dutch artist Jorit, who was arrested in 2018 in Bethlehem for painting a four-metre face of Ahed Tamimi on the separation wall, has also adorned Naples with pro-Palestinian murals.

Jorit's characters - marked by red stripes on their faces reminiscent of scarification techniques used in African initiation rituals - symbolise social resistance.

On the outskirts of Naples, a five-storey building showcases on one entire wall the face of a boy donning a keffiyeh, peering out through a keyhole.

The image symbolises the Palestinian key of return, a representation of the longing for a homeland.

On the island of Ischia, near Naples, one entire wall of a school features a unique depiction of the patron saint of the island. What makes it special is that she is portrayed as a black figure wearing a keffiyeh, with the flags of South Africa and Palestine reflected in her eyes and, again, the "key of return" in one corner of the mural.

Naples in solidarity with Palestine

Support for the Palestinian cause in Naples extends beyond street art, as academic institutions, cultural organisations and solidarity groups actively advocate for the rights of Palestinians.

Interestingly, the name for Nablus comes from the Greek word Neapolis (new city), which holds the same meaning as Naples.

The city's support is evident through its partnership with the city of Nablus, with cultural and educational exchanges taking place regularly in other parts of the West Bank as well.

'No Neapolitan administration has ever closed its doors to the Palestinian community'

– Omar Suleiman, a Palestinian resident of Naples

"No Neapolitan administration has ever closed its doors to the Palestinian community," Omar Suleiman, a Palestinian resident of Naples tells Middle East Eye.

Suleiman was born in 1957 in the village of Nisf Jubeil near Nablus, and moved to Italy in the 1970s.

"My decision to go to Italy was driven by the limited university options in Palestine and because the cost of living was lower compared to other destinations," Suleiman says. “My intention was to study and then go back.”

Instead, Naples has become his adopted home.

According to Suleiman, the people he first met were curious and wanted to learn and understand more about Palestine.

After enrolling on a political sciences programme at the Orientale, Suleiman would also spend time raising awareness about his homeland.

"We visited factories, faculties and schools to share information about Palestine. Despite our limited knowledge of Italian at the time, we communicated our message as best we could," he says.

According to Suleiman, today there are about 70-80 Palestinians in the city.

In 1991 Suleiman opened the Caffe’ Arabo, not far from where Castaldo's murals are located. It has become a vibrant hub for Palestinian and Arab culture, and has been bustling for over 30 years, with author meetings, book presentations and theatrical performances.

Since his arrival in Naples, Suleiman had a vision for the city to be more than just a place to earn a living.

"He has used food, cinema, literature and theatre to promote Palestine," says Caterina Pinto, who studied at the Orientale 20 years ago and is now a university professor of Arabic. She fondly recalls visiting the cafe after her classes.

"I still remember the first time I saw him. He was proudly wearing a T-shirt that read in Neapolitan 'I am from Nablus.'"

In 1996 Suleiman opened Ristorante Amir, where he serves Palestinian specialities including malfuf, maqluba and musakhan.

More recently, he also co-organised the first Palestinian Festival of Naples, called Masarat Al-Fonun - artistic journeys.

The inaugural event featured writer Suad Amiry, poet Ibrahim Nasrallah, director and actor Mohammad Bakri and many others, along with film screenings and the play My Name is Omar, inspired by Suleiman's life experiences.

Even though he has spent 40 years in Naples and become an Italian citizen, Suleiman keeps promoting the Palestinian cause.

"It is something ingrained in me. Coming from a family of farmers, I have a deep connection to the land.

"If you have a sense of justice you cannot be Palestinian and not be tied to your homeland."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.