In pictures: Palestinian women and anti-colonial resistance in the 1930s

Women have been at the forefront of the Palestinian struggle for over a century both during the British occupation of the region after the First World War, and after the establishment of Israel following the second. The rise of both anti-colonial movements in Palestine and the rise of anti-colonial feminist campaigns can be traced to the Buraq Uprising of 1929.

While the ostensible cause of the unrest were tensions between Muslims and newly arrived Jewish settlers over the Buraq or Western Wall, the British administration was also a focus of anger. Palestinians were always against the British colonial project; however, during the uprising, there was an urgency to combat British policies in the region.

Matiel Mogannam, a leading Palestinian feminist at the time, describes the British response to the uprising in her book The Arab Woman and the Palestine Problem, published in 1937, she notes: “Hundreds of men were sent to prison, hundreds of homes unmercifully destroyed, hundreds of children became orphans...Someone must remove the stain that has been added to the history of the Arab people, who were described in a proclamation issued by the British High Commissioner soon after his return leave on 1 September 1929, as 'ruthless and bloodthirsty'."

The Buraq uprising ushered in a new wave of organised resistance against British colonialism and, importantly, it compelled women of all backgrounds to join the fight for freedom. In the picture above, which was taken during the uprising in Jerusalem in 1929, a flag reads “Long live Palestine”. (Library of Congress)

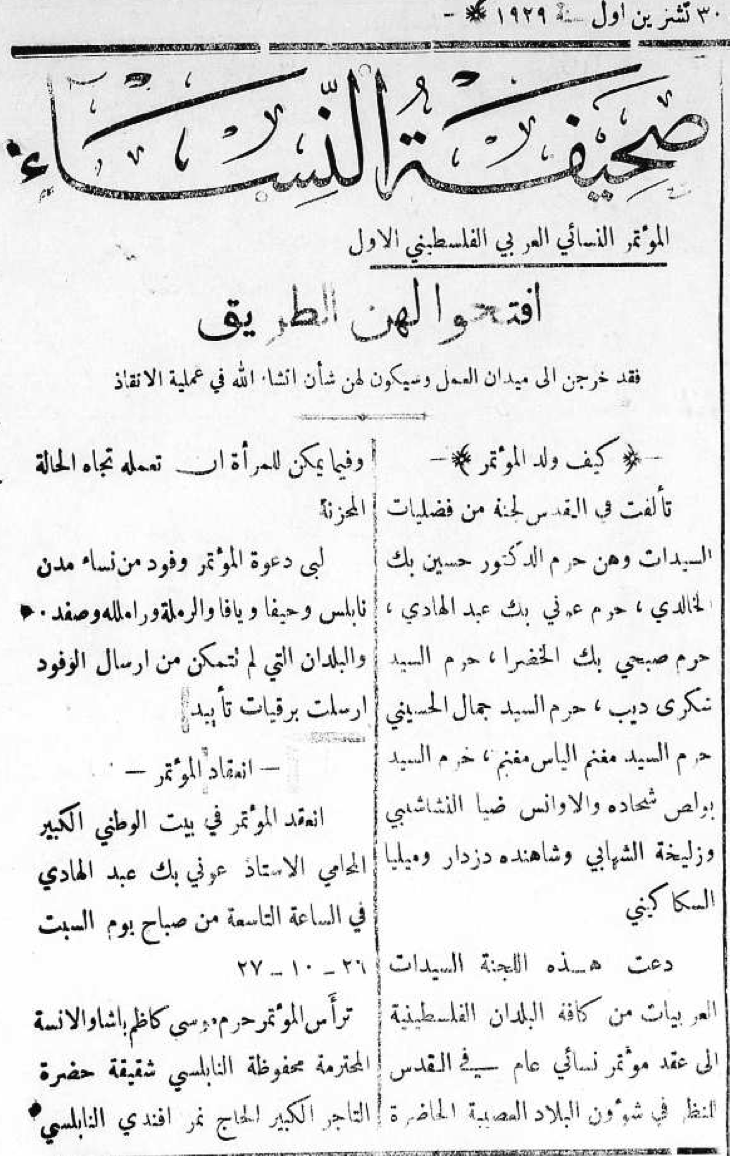

Just months after the Buraq Uprising, the first Arab Women’s Congress was established on 26 October 1929, when over 200 Palestinian women met in Jerusalem to discuss the problems within Palestinian society. The Arab Women’s Congress established a series of resolutions framing their movement, with the two most prominent causes being opposition to the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and Zionist immigration to Palestine.

The women also protested the British policy of police brutality and collective punishment against Palestinians. After this meeting, the Arab Women’s Congress created a memorandum with their demands and marched to the High Commissioner's government house in Jerusalem to present him with their complaints.

Pictured is the delegation of Palestinian women at the entrance of the British High Commissioner's Residence in 1929. Shown are (from left), second: Matiel Mogannam, fourth and fifth: the Nasir sisters, with Nabiha Nasir, founder of Birzeit College at fifth; seventh: Basma Faris, principal of the Mamuniyya School. (Library of Congress)

Although the Arab Women’s Congress was composed of primarily elite women, they were very active and educated on matters relating to the British Mandatory Power and its structures within Palestine. In fact, these women were amongst the first to publicly speak out on behalf of Palestinian farmers and the manner through which British colonialism was exploiting agriculture industries in Palestine, causing devastating impacts in rural Palestine. (Library of Congress)

The Arab Women’s Congress also organised a demonstration during their historic meeting in 1929, in which they marched from the high commissioner's house to the Old City of Jerusalem. The women first demonstrated in cars, driving passed various embassies and government offices in Jerusalem. Then they marched on foot through the Old City of Jerusalem.

Throughout Palestine, more women’s unions and organisations began forming both with the aim of diplomatic dialogue as well as direct militant resistance to the growing threats of Zionism and British colonialism. In 1932, Palestinian leaders met in Yaffa and effectively adopted a resolution of non-cooperation with the Mandatory Government.

Pictured above is a demonstration held in Jerusalem in the 1930s (possibly 1932) led by a group of schoolgirls holding a banner that reads: “No dialogue or negotiations until the termination of the Mandate” amplifying the resolution adopted in Yaffa in 1932. (Wikimedia)

Throughout historic Palestine, many leading feminist pioneers were organising to combat colonialism. One of the most prominent Palestinian feminists was Sadhij Bahaa Nassar, who was the co-editor and writer for El-Carmel newspaper established in Haifa, Palestine in 1908.

El-Carmel was a monumental newspaper that contributed widely to the shaping of Palestinian national consciousness. It helped unify Palestinians against colonialism and Zionism by serving as an essential forum for anti-colonial resistance across Palestine.

In the early 1920s, Nassar dedicated a section of the newspaper to discussing women’s issues and other important social issues. Her articles ranged from discussions on equality between the sexes to increased political activism and nationalism amidst colonial aggression. Her writing focused on Palestinian women in the revolutionary struggle against colonialism.

By 1930, Nassar also co-founded the Arab Women’s Union of Haifa with Mariam al-Khalili which was a militant anti-colonial union dedicated to the liberation of Palestine. In 1938, Nassar was arrested by the British for supplying arms to Palestinian rebels and was imprisoned for almost a year. Like her, many Palestinian women were accused of hiding guns and explosives under their car seats and in their homes.

The clipping above is from the Women’s Section of El-Carmel on 30 October 1929. The section is reporting on the First Arab Women’s Congress that took place on 26 October 1929. (El-Carmel)

The Egyptian Feminist Union (EFU), founded in 1923 by Egyptian Feminist Huda Sharawi, is often credited as the starting point of feminist organisation in the Arab world, and a leading influence for mobilising Arab women across the Middle East.

The EFU championed gender equality in Egypt and was also dedicated to empowering feminist networks throughout the Arab world. It strongly championed the Palestinian struggle against colonisation.

In 1938, the EFU organised the Eastern Women’s Conference for the Defence of Palestine in Cairo. Sadhij Nassar, amongst other Palestinian feminists, attended the conference and gave speeches on Arab unity and the need to collectively combat colonial forces for independence.

Arab women also contributed widely to the resistance efforts during the Great Revolt. In 1938, it was reported that a Druze woman from Lebanon named Hannia Bint Abu Ahmed was caught on the border attempting to smuggle arms into Palestine. Pictured is the Palestinian women’s delegation leaving Lydda in Mandate Palestine to attend the Eastern Women’s Conference for the Defence of Palestine in Cairo. (Library of Congress)

Unlike the women who comprised elite society, fellah women did not engage with the British Mandatory Power through their formal institutions nor did they have access to the tools and resources required for political mobilisation.

Yet the most important figures in the history of Palestine are the fellah women who preserved the foundations of the Palestinian national culture and identity.

Despite aggressive campaigns of colonial violence and erasure, fellah women fought to preserve their heritage and Palestinian roots. They were central forces of resistance that actively participated in militant campaigns against colonial forces that helped sustain Palestinian resistance during the Great Revolt of 1936-39. Pictured here in Jerusalem in 1935 is a peasant woman passing a British soldier on guard. (Library of Congress)

In her book The Nation and It’s New Woman, Ellen Fleischmann documents the name of "Fatma Ghazzal" who was killed during a battle in Wadi Azzoun in 1936. Although this is the only name documented, it was well accounted for that many women fought and died alongside men during the Great Revolt.

In addition, many women were subjected to arrest due to arms smuggling during the Great Revolt. Ellen Fleischmann mentions Tharwa Abdul Kareem of the Palestinian village Saffuriya who smuggled her uncle's gun in a haystack. Other women from various regions of Palestine were imprisoned for years for smuggling and hiding arms during the revolt.

Pictured is a home in Halul village (1936) that was blown up by the British military in Palestine during the Great Revolt. The British enacted great violence through collective punishment campaigns in Palestine that displaced Palestinian women and children. (Library of Congress)

Palestinian women would also serve as messengers on their trips to visit those imprisoned. A famous Palestinian folklore song entitled Ya Taleen el Jabal (Climbing up the Mountain) is an example of a song that was sung by Palestinian women originally in the northern Galilee region of Palestine.

This resistance song was sung as Palestinian women were making their way up the mountain to visit the men imprisoned there.

As they were singing the women would encrypt various parts of the lyrics by adding "L" sounds such as Lelele between words to relay messages to the Palestinian men about escape plans Palestinian rebels had drawn up for those imprisoned.

In addition to these many contributions, it’s important to note the foundational role Palestinian peasant women played in preserving the revolt. Many Palestinian guerillas sought shelter and food in villages throughout Palestine during the Great Revolt. Many British accounts speak of "fellah" (peasant) women who “illegally” provided shelter and assistance to Palestinian fighters.

Palestinian fellah women would also walk for hours to bring food and water to Palestinian prisoners who were staying in horrible prison conditions throughout Palestine. (Library of Congress)

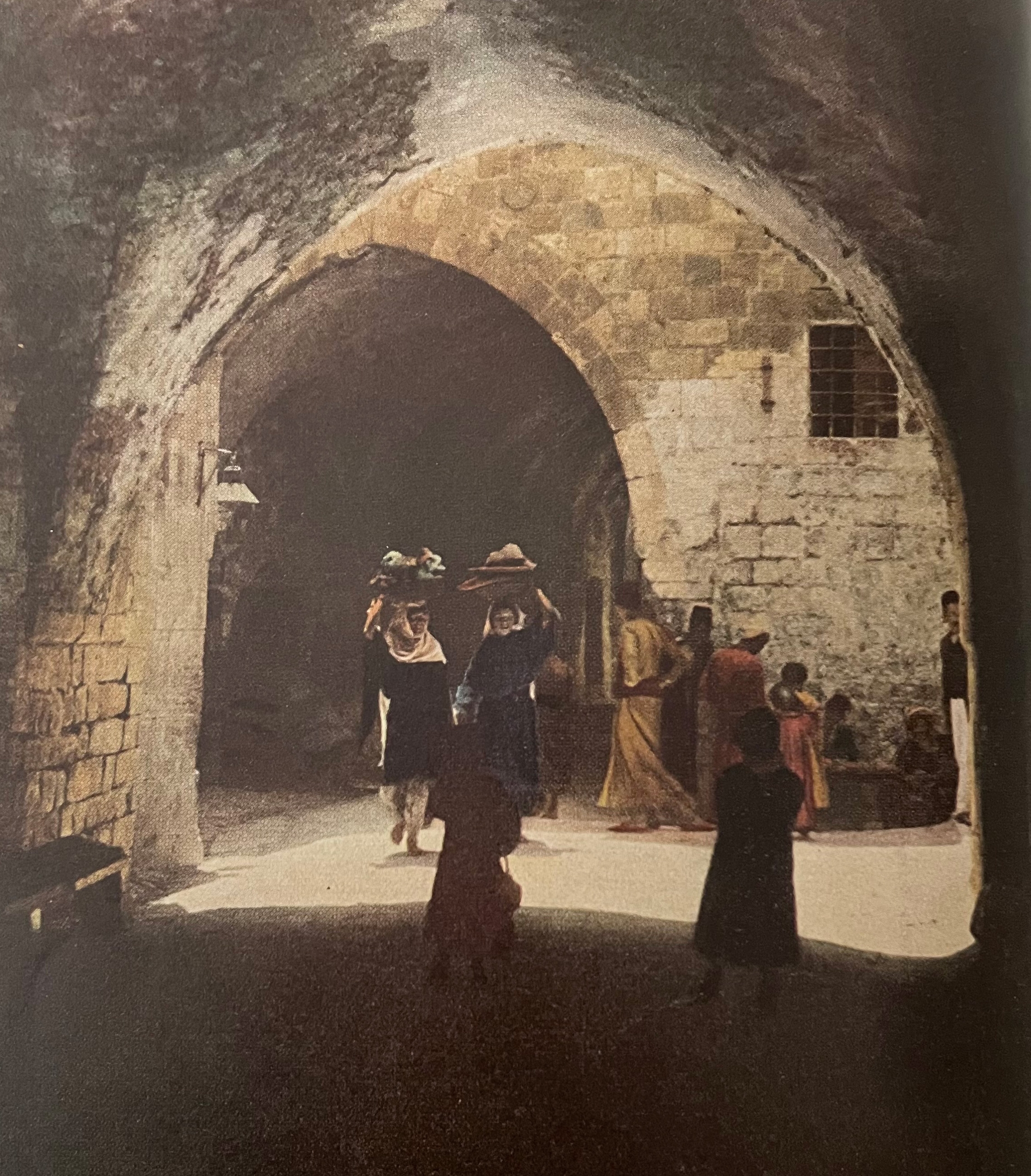

Fellah women were also instrumental in spreading information and relaying warnings of British intrusions in various villages while on daily routes to collect water.

It was noted that many women died in the crossfire between British soldiers and Palestinian rebels in their efforts to warn fellow villagers of the British military presence. In the picture, Palestinian peasant women walk to the Bab al-Habis (Door of the Prison) in Jerusalem with baskets of goods atop their heads in the 1920s. (National Geographic Magazine)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.