In pictures: Tunisia's devoted cat guardians

When asked how many cats she keeps in her bedroom, Meriem Gdoura says "two" in a raised voice - wary of her stepmother within earshot - while mouthing “twelve or thirteen”. The narrow two-storey family home in downtown Tunis houses more than 60 cats, but the second floor is supposed to be (mostly) reserved for humans. (Layli Foroudi)

Gdoura, 35, has always loved cats, but in the last six years her house has accidentally become an animal shelter. She started bringing home needy kittens or injured street cats. The news soon spread and neighbours started dropping their unwanted kittens at her door. (Layli Foroudi)

“They call me ‘mother of the cats’ - om il ktates,” said Gdoura, an engineering graduate currently working in a call centre. “I say to myself, ‘I’ll take this one and then I’ll stop’… and then I would go out and come across an injured cat and think, ‘15 is the same as 16, 16 is the same as 17…’ and then it exploded.” (Layli Foroudi)

Stray cats wander the streets of Tunis in abundance. While it is common for people in the capital to feed street animals - on the main avenue, for example, plastic bottles cut in half are filled with water for cats and dogs to drink from - unwanted pets and their litters are also abandoned. (Layli Foroudi)

They are commonly dropped off at marketplaces, where they have a better chance of getting fed, says Houda Bouchahda, 39, another cat lover who lives in the Tunis suburb of Sidi Hassine and has more than 200 cats, many of them picked up from the market. (Layli Foroudi)

Yosra Jouini, a Tunis-based vet, says that one of the main reasons for the growing number of stray cats is the lack of a sterilisation strategy put in place by the government. “A sterilisation bill at the vet (around £45) is unaffordable for owners and other treatments are also relatively pricey for the average Tunisian,” she said, adding that some locals believe that sterilisation amounts to animal cruelty. One cafe in the Tunis suburb of La Marsa has started taking in abandoned kittens, where they are looked after by the waiters. (Layli Foroudi)

Dalanda (above) works in the cat-welcoming cafe Grignotine, in La Marsa, a Tunis suburb. Cats are left to lounge on the sofas, where they are petted by customers and are offered food and water. The Grignotine team are trying to get permission from the local authorities to convert the space opposite their cafe into a feline play area. Some lucky ones even get a home; recently, Dalanda adopted one sickly cat to nurse back to health. (Layli Foroudi)

A new cafe for Tunisian cats opened this year - not in Tunis, but Pimlico, London. La Maison du Chat is run by Florence Heath, a petroleum geologist, who worked in Libya from 2008-2011 and then in 2012-13. She co-founded Rescue Animals of North Africa (RANA) with a Tunis-based friend and they started organising transnational pet adoption. (Saleem Vaillancourt)

“Living out there made us realise the level of help that they needed, compared to the UK where there are thousands of charities looking after animals,” Heath said. They place 45 cats on an average year but their operations have been disrupted by the Covid-19 travel restrictions. (Saleem Vaillancourt)

Stoufa was flown as an "accompanied pet" from Tunis to Paris, and then driven to London by volunteers from RANA's network. She arrived in February and is spending time in La Maison du Chat while waiting for a new home. Tunisian cats are sometimes adopted by families that have been deemed unsuitable by the RSPCA because of their age or working situation. Grey cats are particularly sought after as they are hard to find in the UK, says Heath. (Saleem Vaillancourt)

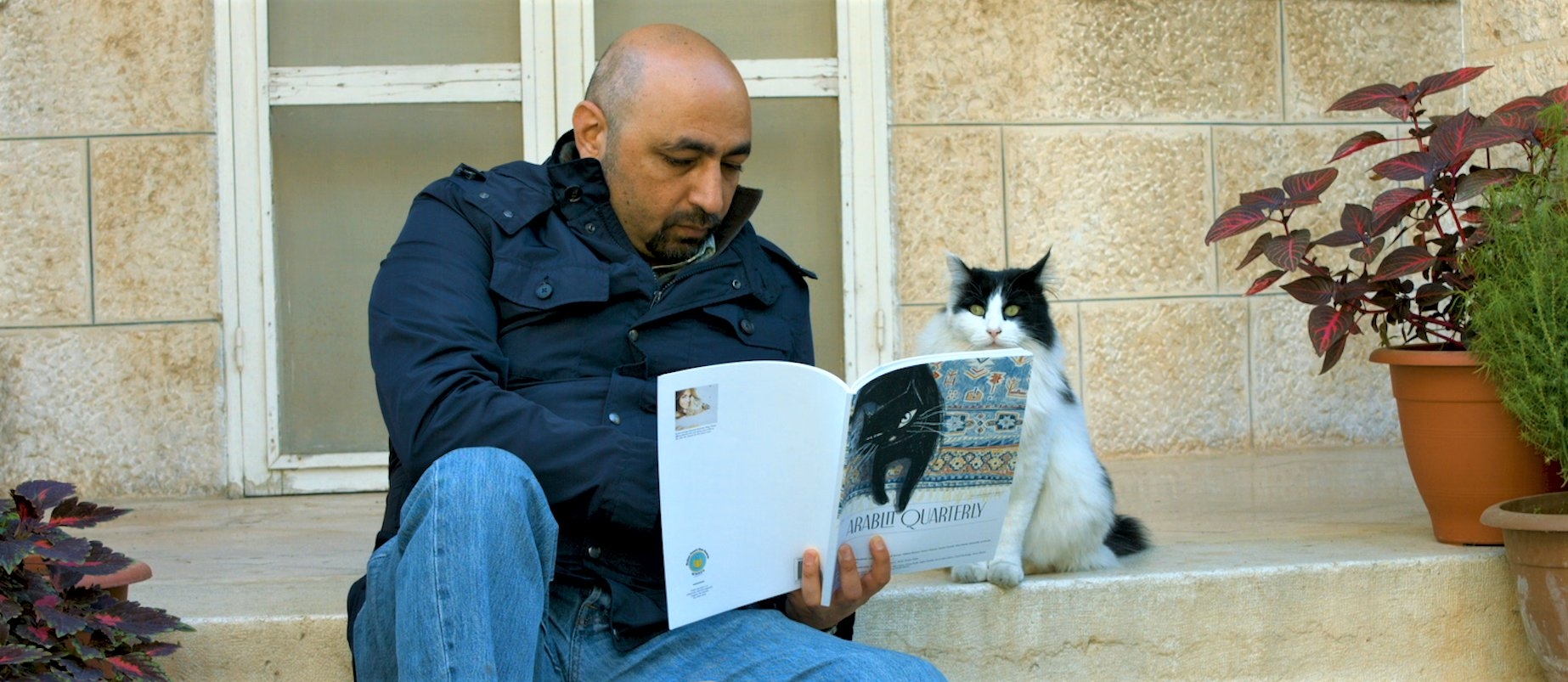

In Arabic literature, cats are often portrayed as vulnerable. There are historic stories that praise caring for animals, says Marcia Lynx Qualey, editor of ArabLit Quarterly, a literary magazine, which dedicated a recent issue to the subject of cats. “In [Egyptian scholar Jalal al-Din] al-Suyuti’s 15th century treatise on animals, we learn that a man’s sins were forgiven because he once showed kindness to a small cat, and a woman went to hell because she had tortured her cat,” says Lynx Qualey. (Courtesy of ArabLit Quarterly)

But animal welfare is not currently a priority in Tunisia, says Nidhal Attia, an environmental activist and project coordinator at the Heinrich Boll Foundation, who took part in a 2012 protest calling for animal rights to be written into the new constitution, which they weren't. “People [passing by the protest] didn’t accept this idea - there were insults, offensive remarks to say that we need to win the basic rights of humans before thinking about animals.” (Layli Foroudi)

Gdoura is trying to balance caring for herself and caring for her cats. She is trying to reduce her cat load to a “manageable” number, like 20, so that she can give her cats a better life and get some of her own life back. Some cat rescuers need rescuing, too. “I complain that I am tired, that I want to regain my life, but this cat is a life also.” (Layli Foroudi)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.