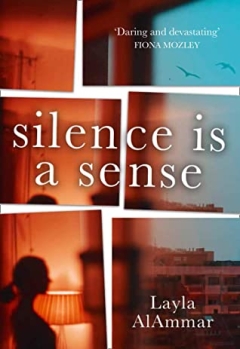

Silence is a Sense: Writing the traumas of war and displacement

“No one is truly voiceless … Either they silence you, or you silence yourself.”

The narrator of Lancashire-based Kuwaiti author Layla AlAmmar’s second novel, Silence is a Sense, spends her days writing and standing at the window of her flat in an unnamed and quiet English city, watching her neighbours. Among them are an elderly couple, a fitness enthusiast, an abusive father and husband, and a single man who regularly takes a box from under his bed and contemplates its contents, hidden from her view.

She cannot speak, or rather, does not speak, according to her doctor.

Stunned into silence by the traumas of war in her native Syria and by the journey across Europe as a refugee, she seeks solace in her books and keeps a secure physical and emotional distance from her community, rarely venturing beyond self-imposed confines, “invisible borders” that reduce the size of her world to a small safe zone.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Under the pseudonym “The Voiceless,” she writes articles for an online magazine whose editor seems all too eager to milk her tragic experiences for tantalising content, or at least that which will fit her preconceived notions about what a Muslim refugee woman ought to say and think.

“Why don’t you give us some of your memories instead?” her editor writes to her, either oblivious or wilfully indifferent to the psychological consequences of unearthing those adversities and serving them up to an audience.

All-seeing eye

The Syrian civil war, with its senseless brutality and decimating force, is a forbidding presence in Silence is a Sense.

Its horrors reach the reader through the narrator’s nightmares and painfully exhumed memories: of the crushed hope of the Arab Spring; of barrel bombs falling; of family and friends tortured and killed; of an angel of death hovering over and stalking civilians in the streets; of a lover who joins the nascent White Helmets because it means “doing something” in the face of a tyrant who would demand total subjugation.

Her pathological reluctance to speak is a testament to the pervasive and lingering fear of living under the all-seeing eye of a ruthless surveillance regime where the “only safe space is the one between your ears or in the grave”. We learn it is no wonder our narrator is silent.

“When you come from a place where the walls have ears and you spend your life hiding and fabricating, trying to learn the rules to games you have no hope of ever winning and searching for cracks from which to scurry out, your instinct is to hold certain matters close to the chest.”

Her ordeals, both back home and during the arduous trek across Europe, have left discernible marks on her, as exquisitely expressed in one of many poetic passages:

“Shall I tell you… how the topography of her, of Europe, is encoded in my body now? She’s in the limestone of my skin, dry and easily split. Her salt is in the dark seaweed of my hair, the tang of my sweat. My breasts, the hills of Serbia. The rolls of fat on my belly, my back and hips, like the creases and trenches of Macedonia. Her marshes and fens lie in the shadow of my armpits, the morass of my mound. Walking across Europe, I hung myself from the sky. I swung from star to star and curled up in every crescent moon.”

Stifled voices

It is no easy feat to deliver an engrossing story through a narrator whose interactions are limited by her inability to speak, but AlAmmar uses this device to denude her other characters of the societal constraints that would otherwise lead them to censor themselves around her.

“When you can’t speak, people assume you can’t hear either,” the narrator writes, adding to the catalogue of expectations foisted upon her on so many fronts, many of which she defies in refusing to abide by them.

"I am a girl with no name, a girl with no face. I can be whatever you see. Arab. University student. Writer. Fatty. Muslim. Whore… I am all these things at once. I am none of them.”

To mistake the narrator’s muteness for meekness, however, would be patently foolish: she holds strong beliefs and expresses them no less strongly through her writing.

When she opines on topics she is uniquely positioned to comment on - the condition of refugees and the various prejudices they face in their host countries, for example - she is told by her editor to write about her experiences.

When she does, she is told that they are too harrowing to be authentic. Repeatedly and on various levels, her voice is stifled.

Her status as a refugee and as a Muslim woman who takes no pains to sugarcoat her thoughts on contentious issues (an example being the question of who may lay claim to Islam), only further narrows the margins within which she is allowed to express herself in ways acceptable to readers who “aren’t interested in the truth so much as the narrative”.

The expectations set for real-world writers of similar heritage - namely, to serve as spokespersons for their culture and to refrain from negative appraisals of any of its facets in order to not bolster racist stereotypes - come to mind.

Silence is a Sense is a fearless novel that engages with topical issues head-on. The narrator’s refusal to participate in her community and her retreat into herself are artfully mirrored in the form of the novel and its quasi-claustrophobic quality.

We spend more time within her head than outside of it, either in action or dialogue. The result is a profound plunge into the territory of trauma, expertly mapped by an author who knows that there is comfort to be found in pessimism, in the false sense of safety that negativity provides because it offers the illusion of being ready for the worst.

This proves ultimately deceptive, as the narrator learns when confronted with a series of events that call on her to use her voice, among which is a vicious attack on a mosque by a perpetrator whose identity only she is privy to. The price of silence is high, and she will have to decide whether it is worth the weight of guilt on her conscience.

Marketed as a mix between Rear Window and Exit West, Silence is a Sense by Layla AlAmmar is the author's second novel. It follows her 2019 debut The Pact We Made, which tells the story of a Kuwaiti woman trying to balance her traditional upbringing and modern lifestyle. Both books are available from The Borough Press

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.