Under the skin: How lightening creams exploit the beauty myth

Young women in the Middle East are all too familiar with the notion that to be white is to be beautiful.

Family and relatives advise the younger generations to stay out of the sun during the hottest part of the day, not just to avoid burning, but also, heaven forbid, in case their skin unfashionably darkens.

The vanity cabinets and bedside tables of the Middle East are permeated by the powdery, slightly floral scent of lightening creams as millions of women slather on thick white layers as part of their daily regimes.

Beauty adverts are everywhere, selling the dream of lighter skin in weeks and offering colour charts against which pigmentation can be measured.

It is no surprise, then, that there’s a booming market for skin lightening products, despite the moral and physical concerns associated with some cosmetics.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The market is huge: the Guardian reported that in 2017 the global industry was worth $4.8bn (£3.4bn), projected to grow to $8.9bn by 2027.

But it is an industry not without its risks. Sarra el-Badawi is a British-Sudanese doctor who works in the UK but regularly visits Khartoum. She said that in eastern Africa there is a growing culture of glorifying lighter skin.

"There are some men who will only marry a light-skinned woman; there are songs glorifying light-skinned women; there is increasing normalisation of this kind of language in Sudanese society. This has now become the way females see value in themselves.

"You just have to walk down the street in Sudan where you will see countless women walking with red-raw skin, hiding from the sun, to be able to see the harsh realities of the skin lightening and bleaching products."

Down the street in Sudan you will see countless women walking with red-raw skin

- Sarra el-Badawi

El-Badawi said that she has heard anecdotal reports of women suffering sun burn and adverse reaction from some types of cream. "Their sun burns after sun exposure because of the damage to the protective layers of the skin as a frequent consequence of the creams."

Many creams contain steroids, mercury and hydroquinone, according to the UK's NHS.

Reported side effects among some users vary from skin irritation and burns to, in more serious cases, thinning of the skin, scarring and kidney and liver damage. Some ingredients can cause birth abnormalities if used during pregnancy.

Anjali Mahto is a consultant dermatologist at the British Skin Foundation, a UK-based charity that funds research into skin diseases and cancers. According to Mahto, untested skin whitening creams are promoted around the world in Pakistan, the Middle East and the Caribbean among others.

"It is illegal to sell products in the UK without a supplier's name and address plus a list of ingredients," she said. "If a product is missing these key pieces of information then they may be illegally imported and could contain banned ingredients."

However, in the Middle East, more relaxed regulations mean that such creams can be sold over the counter in markets and stores without warnings or detailed information.

According to the NHS, although products in Europe and the Middle East that promise to lighten and brighten are unlikely to be harmful, there is no guarantee that they will actually work.

Mahto told MEE: "Hydroquinone is still probably one of the most common agents. It works by inhibiting production of the pigment melanin, which gives skin its colour. Its overuse can damage elastin strands in the skin, causing premature ageing and weakening of skin.

It is very clear that cosmetics are being used in South Sudan without any discrimination

- Mawien Atem Mawien, DFCA

"Prolonged use will result in skin thinning or atrophy, stretch marks, easy bruising and broken veins. There is an increased risk of infection and boils. Over time, long term use, particularly over the whole body, can interfere with blood pressure, cause diabetes, osteoporosis and weight gain."

In January, South Sudan's Drugs and Food Control Authority (DFCA) banned the sale of the products to regulate imports and minimise, it said, the harmful effects on the skin.

Mawien Atem Mawien, secretary general of the DCFA, said: "It is very clear that cosmetics are being used in South Sudan without any discrimination despite the fact that they contain so many chemicals.

"No cosmetics will be brought to the Republic of South Sudan without the approval of DFCA. Anything outside the right channel will be deemed illegal."

South Sudan is following the lead taken by Rwanda, South Africa, Kenya and Ghana among others - but such products still remain on sale in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, where more relaxed regulations allow them to be sold without restrictions.

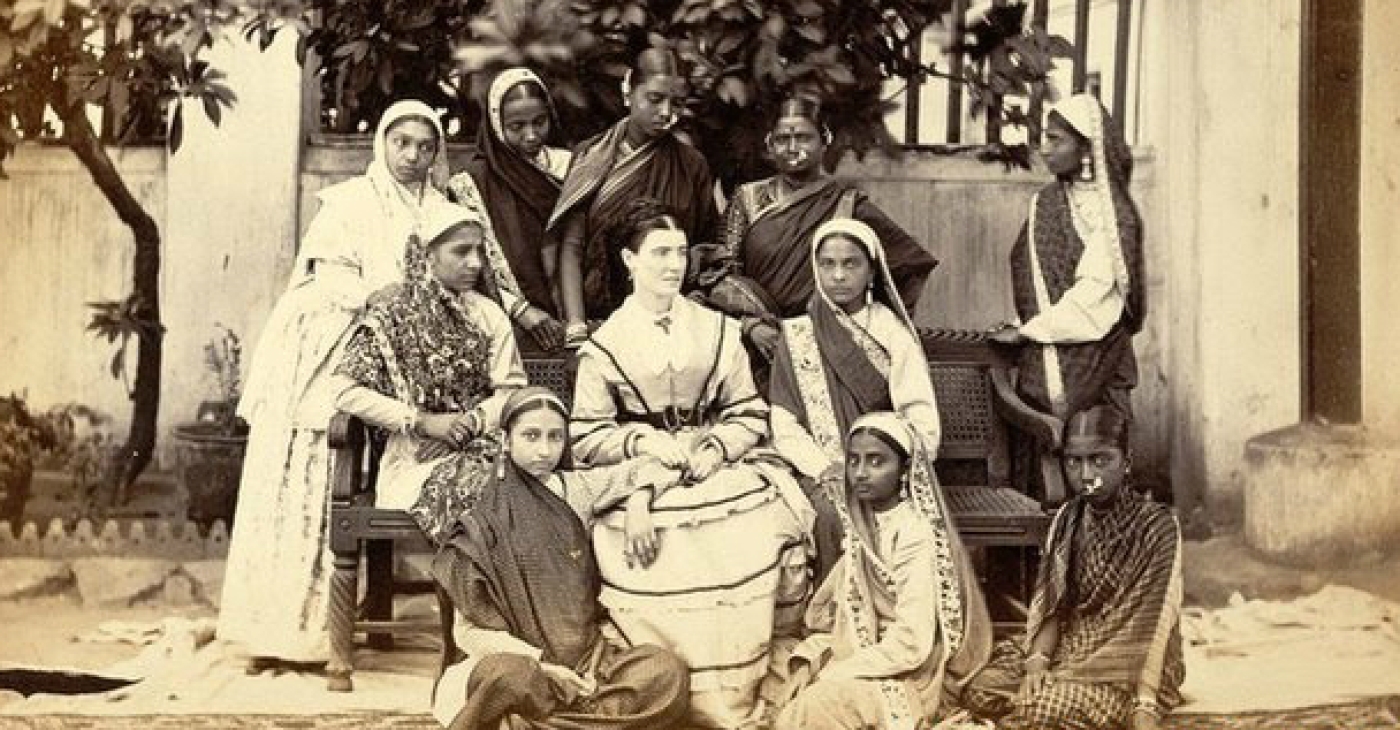

The colonial hangover

Despite the risks associated with a number of these creams, their popularity continues to grow.

In the region, beauty norms are deep-rooted and ideals established in the colonial era have proven hard to shake. After all, power permeates a society and with white Europeans in charge, being lighter skinned came to be seen as being preferable for the imperial subjects of the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

The superiority enjoyed by Europeans in the political and economic life of colonial nations was naturally replicated when it came to establishing what did and did not look good.

"In Sudan, although the country was not part of the British Empire, they certainly left their mark there," says el-Badawi.

"This is the long-standing aftermath of the imperialists who tried to establish the British Empire, when they tried to impose themselves on the Sudanese people under the guise that they were 'civilising' the nation. They made it known they were superior to the Sudanese people."

She said that this has now affected how some Sudanese see themselves.

"There is a clear general preference towards light skin. Everyone knows someone who has participated in skin lightening or bleaching, whether it's a grandmother or a young cousin, there is no age limit to this activity."

Lighter skin, critics argue, has become a social signifier of ranking and superiority in some societies, that may affect anything from an individual's marriage prospects to job opportunities.

Eman Mohammed, 27, from Cairo, said that in Egypt friends and family increase their use of creams ahead of major social occasions.

"These creams are very popular where I'm from, many people depend on them from teenagers all the way to 40 years old, to look whiter," she said

"There's a massive societal pressure on people, especially for young girls with darker skin as they always get compared to their peers in terms of beauty and skin colour."

There's a massive societal pressure on people, especially for young girls with darker skin

- Eman Mohammed

Lenor Sonkor, a British Egyptian, said she was "influenced and brainwashed" into buying creams by advertising in the Middle East, which presented lighter skin as more beautiful. It was something she blamed on marketing and cosmetic companies - until she realised she was wrong.

"Generations grow up watching Hollywood movies where actresses and models are all light skinned and look perfect ... Middle Eastern media has also picked up on this, and you'll notice that Arab and Turkish actresses are all fair skinned."

Earlier this year, Khadija Ben Hamou, the newly crowned Miss Algeria, received an onslaught of racist comments and abuse because of her skin colour. Critics made remarks about her features and darker complexion, saying it did not represent the beauty of Algeria.

But others online sprung to her defence.

In a TV interview with TSA, Ben Hamou said she was proud of her identity. "To those who criticise me, I ask Allah the Almighty to bring them back to the right path. On the other hand, I thank those who encouraged me."

She also encouraged others to take part in the competition, despite the racist comments and criticism she received online.

"I am honoured that I have achieved my dream, and I am honoured by the state of Adrar where I come from," she said.

According to writer and analyst Hana Al-Khamri there is almost no public debate about racism in Arab society.

"On the contrary, there is a popular outright denial that racist attitudes against black people exist ... every dark skinned person in the Middle East has been exposed to racial epithets and has been called different derogatory names."

Cosmetics companies hit back

Cosmetic brands have come under fire for their skin lightening campaigns and advertising across the Middle East and Africa.

Nivea, which is owned by the German company Beiersdorf, has been criticised following a campaign launched for its creams in Africa. In an advert from 2017, a black woman says: "I need a product that I can really trust to restore my skin’s natural fairness."

The brand was again criticised in April 2017 for a campaign targeted at Middle Eastern consumers with the slogan, "white is purity".

In a statement on its website, the company maintained that it didn't promote skin lightening.

"Whereas Europeans often wish to have a tanned skin, beauty in Asia and Africa is often connected to a lighter complexion. As a manufacturer of cosmetic products, we try to develop products which respond to these cultural preferences; however, of course always in line with current health and safety requirements."

Another brand known for its skin lightening creams is Fair and Lovely, made by the Anglo-Dutch, India-based company Hindustan Unilever. A spokesperson for Unilever said that it does not equate or sell the idea that lighter skin is more desirable through its products.

"We recognise that the marketing of these products has sometimes insinuated the notion that dark skin is undesirable. We have strict marketing principles that explicitly state that we will not make any association between skin tone and a person's achievement, potential or worth."

But the campaigns against the companies continue. Fair and Lovely, for example, has been criticised for adverts that suggest users will become famous and attract attention after applying its creams.

In 2016, the hashtag #UnfairandLovely went viral as part of a challenge against colourism. Thousands of women shared images of themselves, challenging ideologies that they said are rooted in colonialism.

El-Badawi believes that social attitudes have had a lasting impact on people, and continue to create a market for skin lightening products.

"As long as people are internalising the shadism that is at play, then skin bleaching and lightening will continue to be popular."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.