The Spanish Civil War's forgotten Arab Republicans

Almost exactly 85 years ago, the fate of the Spanish capital Madrid was at stake as insurgent Nationalist forces began their assault on the city and its Republican defenders.

The key military component of the offensive, which began on 8 November and would last until the city's fall in March 1939, were Moroccan soldiers who served under Nationalist leader and later dictator General Francisco Franco in his Army of Africa.

That Arab presence in the Spanish Civil War is a fact widely acknowledged in history books. What is less well known is the part played by Arabs in the Republican cause.

The siege of Madrid, a 28-month long standoff over control of the city that followed the November 1936 assault, lasted as long as it did in part because of the support the Republicans received from the International Brigades. These were military units made up of foreign volunteers from across the globe - mainly fellow Europeans - who arrived in their thousands to defend the Spanish government.

By 9 November, the 11th International Brigade, numbering 1,900 men, were at the Madrid front. Quite likely among them were a number of Arab volunteers.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Arabs defending the Republic

Due to limited documentation and a lack of historical oversight, little is known about the Arabs who took up arms to defend Spain and protect it from the clutches of fascism. As a result many of the names of Arab volunteers remain unknown.

Determining their exact number is an arduous task too, with some historians claiming up to 1,000 Arabs joined the International Brigades.

However, the Catalan historian Andreu Castells, who has conducted extensive research into the topic, found 716 recorded cases.

The disparity in the figures was a result of irregular record keeping among the Republican forces, mistranslations and confusion due to colonial citizenship.

Many of the Arabs who volunteered were registered as French citizens, as many North African countries were still under colonial rule when the Spanish Civil War broke out. Additionally, Arabic names were commonly misspelled and therefore registered multiple times.

Roughly half of the Arabs who volunteered in Spain were Algerian, with 493 joining the Republican forces, of which 332 survived.

“There was quite a strong anarchist movement in Algeria at the time, which motivated many to join, but practically it was easier for them to reach Spain as there were direct boats from Oran to Alicante,” says Egyptian filmmaker Amal Ramsis, who directed You Come From Far Away, a documentary on the Arab presence in the Spanish Civil War.

According to Castells’ figures and the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History, 211 Moroccans, 11 Syrians, four Palestinians, three Egyptians, two Iraqis and one Lebanese man also took up arms for the International Brigades.

The motivations behind Arab participation in the Spanish Civil War are varied, though Ramsis believes they were driven by the ideal of their own future liberation.

“Arab volunteers didn’t just enlist out of solidarity with Spain, but also to defend their own future," she says.

"For them, a Republican victory in Spain would mean the decolonisation of the Arab world in the longer term, it would be the beginning of their liberation."

A Palestinian on the frontlines

One of the most prominent Arabs to participate in the civil war was the communist Palestinian journalist Najati Sidqi, who believed the downfall of European fascism would enable greater self-determination and independence among Arab peoples.

“There is no excuse for excluding the Arabs from volunteering. Are we not also demanding freedom and democracy?" he wrote in his Memoirs of a Palestinian Communist in the Spanish International Brigades.

"Would not the Arab Maghreb (Northwest Africa) be able to achieve its national freedom if the fascist generals were defeated?”

Sidqi recalls introducing himself to Spanish local government militias by saying: “I am an Arab volunteer, I have come to defend the Arabs’ freedom on the front in Madrid. I have come to defend Damascus in Guadalajara, Jerusalem in Cordoba, Baghdad in Toledo, Cairo in Andalusia, and Tetouan in Burgos.”

Palestinian Communist Najati Sidqi was born May 15, 1905. A student at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, Sidiqi fought in the Spanish Civil War where he failed to persuade the Spanish Communists to agitate for Moroccan independence. #OTD #Palestine #Antifa pic.twitter.com/42ilnBcmX3

— The History of Socialism (@TheHistoryOfSo1) May 15, 2021

Sidqi did not formally enlist in the International Brigades but was instead sent to Spain by the Communist International (Comintern) on a propaganda mission to destabilise Nationalist forces.

He arrived in the country in August 1936 posing as a Moroccan under the alias Mustafa ibn Jala, and was tasked with conducting propaganda aimed at encouraging Moroccan forces fighting on the Nationalist side to desert.

In the course of that goal, Sidqi wrote in the Communist newspaper Mundo Obrero, formed the Hispanic-Moroccan Antifascist Association, orchestrated radio broadcasts in Arabic, spread pamphlets, and visited the trenches along the front lines urging Moroccans on the other side to join the Republican ranks.

Megaphone in hand, he is reported to have said: “Listen to me brothers, I am an Arab like you. I advise you to desert those generals who treat you so unfairly. Come with us, we will welcome you as we should, we will pay each of you a daily salary and whoever does not want to fight will be taken back to his country.”

His attempts to encourage mass desertion were mostly futile. Few Moroccans left Franco’s ranks and he made the mistake of delivering his messages in classical Arabic, which many of the Moroccans serving under Franco did not speak or read.

Republican racism

The ideals the Republican side purported to defend and which drew many Arabs to the cause were not always put into practice.

Many Arabs, who fought with the Republicans, were treated with hostility and experienced racism at the hands of their Spanish brothers in arms.

Distrust towards Arabs was commonplace in Spanish society at the time, driven by historical divisions, racial prejudice and negative stereotypes, and upheld within the Republican press.

“There was intrinsic racism in Republican media, it exacerbated the historic prejudice that was ingrained in Spanish society. The image they portrayed of Moors and Arabs was humiliating and completely dehumanising,” says journalist and historian Marc Almodovar.

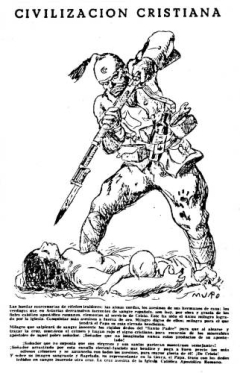

For example, in one cartoon titled "Christian civilisation", which was published by the Republican newspaper Fragua Social, a Muslim soldier is depicted attacking a woman and child- a crescent and star clearly visible on his eastern style helmet.

Sidqi writes about this widespread distrust when describing his first encounter with Republican militias upon his arrival in Barcelona, where he recalls being greeted with incredulity.

“Are you really an Arab? You’re a ‘Moro’ – a Moroccan?" he was asked by one man.

"That’s impossible, the Moroccans are marching with the fascist thugs, attacking our cities, killing us, plundering us, and raping our women,” he was told.

Underlying this attitude was an inability to understand the Arabs they encountered as individuals with their own moral agency, Almodovar tells Middle East Eye: “Everything was bathed in that racism... (they were) not considering them to be political beings with their own criteria and political agenda.”

The heavy presence of Moroccan soldiers in Franco’s forces reinforced and worsened existing negative stereotypes of Arabs.

Sidqi’s pro-Arab proposals were also met with resistance from the Spanish Communist Party, in particular from Dolores Ibarruri - known for her famous "No pasaran!" slogan issued during the Battle for Madrid and one of the party’s figureheads at the time.

The creation of Sidqi's Hispanic-Moroccan Antifascist Association also caused tension among the party.

His plans to deprive Franco’s forces of cannon fodder by inciting an anti-colonial revolution in the Moroccan Rif were strongly rejected. Ibarruri allegedly shut down any talk of an alliance with the “hordes of Moors, beastly savages, drunk with sensuality who rape our women and daughters.”

Frustrated by the hostility among the Republicans, Sidqi left Spain in December 1936.

“There was a complete lack of trust towards any Moroccan," he recalled. "More than once we were surprised to learn about the [Republican] murders of Moroccan prisoners. I understood in the bottom of my heart that my mission was failing. "

Moroccans fighting for Franco

Arabs fighting on the Republican front were vastly outnumbered by Arab members of Franco’s Army of Africa, on which the dictator relied heavily throughout the conflict. The Army of Africa was made up of approximately 60,000 Moroccan soldiers, around 18-20,000 of whom were killed.

The Army of Africa was a legacy of the Rif War of the 1920s and was made up of local recruits from across Northern Morocco. Many were convinced to join the Nationalist cause under the pretext of a collective religious duty, against the anti-religious Republicans, as well as by the financial rewards of fighting.

“There were attempts to mobilise recruits onto the Nationalist side by talking about their joint struggle against atheism," says Sebastian Balfour, a historian and professor of contemporary Spanish studies at the London School of Economics.

"Fundamentally it was an opportunity for very, very poor people to make some money for their families.”

Though a key component of Franco's forces, Balfour explains that “they were basically sent as cannon fodder into battle.”

Nonetheless, the Nationalists paid particular respect and attention to their religious needs, bringing imams along with them and allowing for daily prayers.

“They were going to treat them as well as possible because they were the shock troops of the Nationalist cause. They were precious to the Nationalists as battle hardened troops that they did not have among the Spanish,” Balfour adds.

At the end of the war, Franco appointed the Guardia Mora - Moorish Guard - as his personal ceremonial escort. Riding horseback and draped in white and red hooded cloaks, the Guardia Mora flanked his Rolls Royce during official parades until it was dissolved in 1956.

However, Franco’s gratitude towards the Moroccans who fought for him was limited. Those who served were promptly set aside at the war’s conclusion, dispatched back to Morocco often with nothing more than a miserly pension.

“There was a certain degree of disinterest in the fate of the veterans of the civil war by the new Nationalist authorities. Apart from the pensions, I don't think there was much attention paid to the kind of condition that they lived in on returning to Morocco,” Balfour says.

Speaking in the documentary The Forgotten, a Moroccan who fought for the Nationalists sums up his experience: “Franco was an ungrateful bastard, after winning the war he forgot about us. We were no longer useful to him.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.