Forget Game of Thrones: The master of the cliffhanger is back

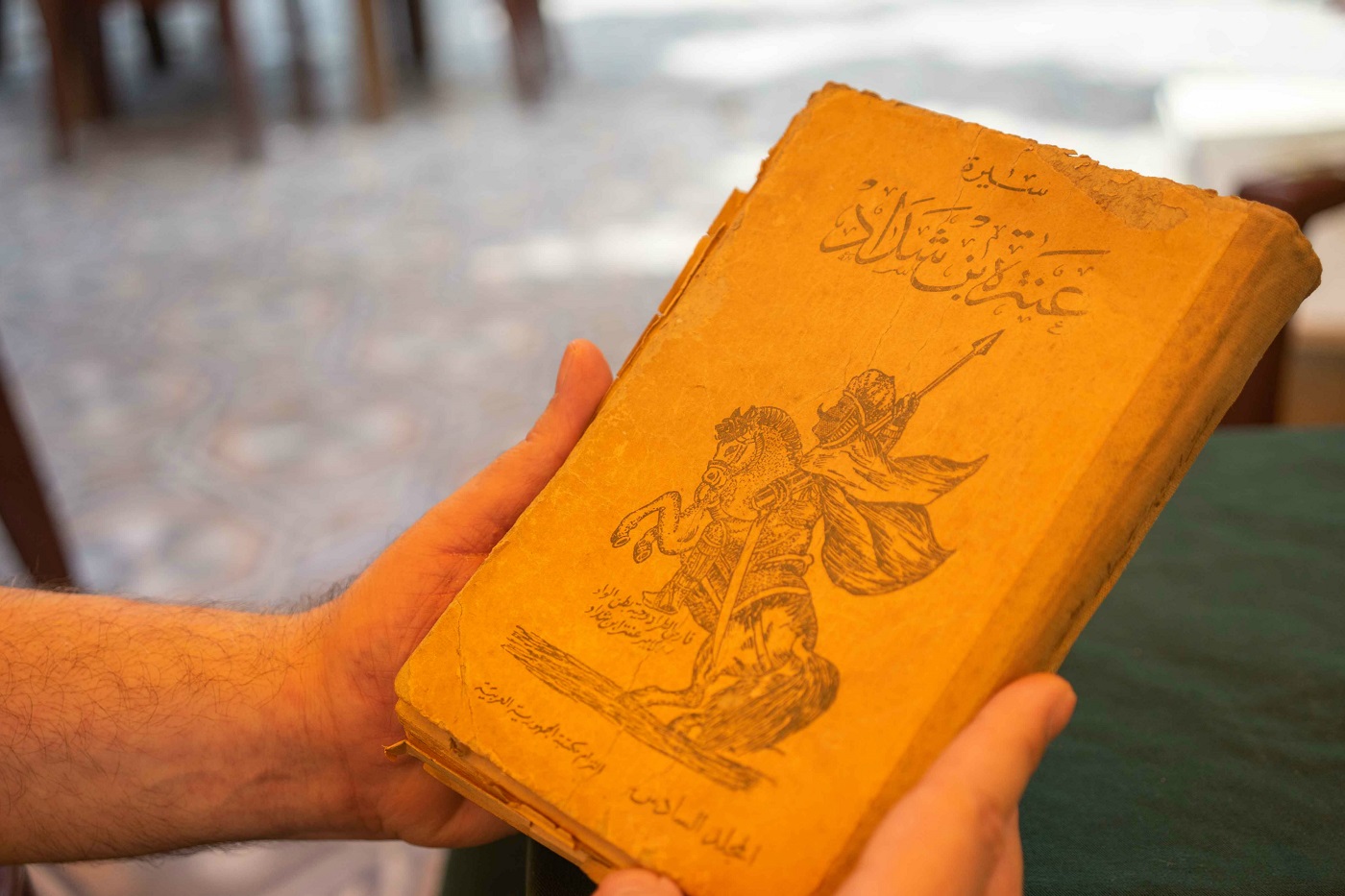

“Antar fought until his hands were tired and numb. Then his horse threw him off and he felt that death was near. Men rushed to attack him and he fought them all, stacking them one on top of another like fallen leaves…But his enemies overcame him, taking him prisoner in a state of humiliation and shame.”

At this point, Nazih Kamareddine stops. His audience, a mix of young and old faces at a crowded cafe in North Lebanon, is left in suspense: they must wait another evening to know what befalls the romantic hero of the poetic saga Antar and Abla.

It’s a technique often used by hakawati, traditional storytellers in the Middle East who serialised their sagas over weeks or even months to draw listeners back. Ahmad al Saidawi, a renowned 18th-century hakawati, is said to have spun out the story of King Baybars for 372 nights in an Aleppo cafe, only cutting it short when an Ottoman governor begged him to disclose the ending.

In previous centuries hakawati (from the Arab word “hakaya” which means story), were part of daily life in the Levant. Often, the practice was passed down through families, each storyteller putting their own distinctive spin on the old tales.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Techniques and tastes varied: religious stories, for example, were common in Lebanese mountain villages, says Jean Hajjar, chairman of the Cross Arts Cultural Association.

The cliffhanger was a popular tool. The hakawati was like a human precursor to a TV series or box-set – people would gather in cafes or the street to tune in for the latest chapter. “It was entertainment: the hakawati brought everyone together,” says Rima Husseini, a professor of cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution at the Lebanese American University.

Once upon a time

Storytelling is rooted in Lebanese culture but in recent decades modern media has eclipsed oral traditions and the hakawati risk being consigned to history. Yet the old tales still resonate with today’s listeners and the practice has resurfaced in new forms as contemporary storytellers find ways to keep it alive.

The Lebanese Ministry of Culture is petitioning UNESCO to add hakawati to its List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, which safeguards traditions that preserve cultural diversity and promote understanding.

“Narratives today are so divisive. The hakawati is a reminder of the shared customs that used to unite communities,” says Husseini. “He can be an antidote to the danger of a single story.”

It’s unclear exactly when the hakawati emerged in Arabic culture. An early example of the influence of the spoken word, however, can be seen in the eighth-century classic One Thousand and One Nights also known as Arabian Nights. In it, the fictional storyteller Scheherazade ends each night on a cliffhanger, forcing the king to delay her impending execution for another day. Eventually, after 1001 nights she secures a reprieve.

One storyteller even staged a wedding scene and asked his audience to dress for the occasion

During the 1940s and 50s, two famous hakawati held sway in the coffee houses of Tripoli in north Lebanon, a city famed for the prowess of its storytellers. Each had a different hero who captured the imagination of loyal listeners. “People used to compete and say our hero is better than yours,” says Barrack Sabih, who has been a hakawati for 12 years.

The storytellers would act out parts of the plot to engage the crowd; one even staged a wedding scene and asked his audience to dress for the occasion. “There were hakawati in all the cafes then, maybe 20 or 30 in Tripoli, and everyone would meet to hear them speak. They had fun with these old stories,” says 85-year-old Hasan Sasaby.

Some travelled abroad in search of exotic material to outshine their rivals, but there was always a demand for the classics. One wealthy listener became so involved in the drama of Antar that according to legend, he went to the hakawati’s home at 2am and gave him a gold lire to buy back the hero’s freedom. “The stories around the stories are almost as compelling as the tales themselves,” says Hajjar.

As educated men, professional storytellers wielded considerable influence. When the celebrated hakawati Abou Ali Ambouba complained of a bad stomach after eating at a well-known bakery, they offered him free sweets to keep it to himself. “They were like the Facebook of that era,” says Hajjar. “In Tripoli they had real power.”

The moral of a good story

Much has changed in Tripoli, where older generations recall playing in the streets with friends of all faiths before the Lebanese civil war, from 1975 until 1990, fractured a tolerant society. “Life before the war was better, people cared for each other and there was more tenderness,” says Sasaby. “They were beautiful days."

Sabih wants to restore Tripoli's identity by adapting old tales to engage a modern audience that, he says, has lost its links with the past.

When he first performed in 2010, older members of the audience wept. “It took them back to a beautiful phase of their lives.” But he is not simply recycling old favourites. Sabih wants to use the role as a cultural tool to educate youth about peace and diversity and discuss issues that are difficult to broach in daily life.

During Ramadan, he performed at a neutral venue situated between Sunni and Alawite neighbourhoods, where buildings spotted with bullet holes are a sharp reminder of the area’s sectarian violence. In doing so he hoped that diverse audiences would come together and mingle in the same public space. “The hakawati is coming back to rehabilitate the meaning of community,” he says.

Some though, harness the tradition for commercial gain, or to reinforce religious dogma, Sabih says. “That’s not a good investment in a diverse place like Lebanon. The value of these stories is in celebrating different points of view.”

In previous centuries, many Levantine villages had their own hakawati, but the best travelled around, captivating audiences with folktales, myths and legends. There were female storytellers too, and people would go to the villages to hear them speak.

Paul Mattar is director of Theatre Monnot in Beirut, which is recording these old village tales so that professional storytellers can keep them alive in the capital’s theatres. “This is a living family tradition,” he says

Can such a medium still hold the attention of digital-age audiences? Mattar thinks so.

“I don’t pretend we can compete with the iPhone or computer, we don’t fight with the same weapons. But when they come to our events people are able to get away from technology and modernity and get lost in a different world.”

Next year marks the 20th anniversary of the theatre’s International Storytelling Festival, which gathers performers from diverse storytelling cultures from around the world.

Other modern initiatives have sprung up in Beirut, including Hakaya, where participants gather to share 10-minute first-person experiences. Rima Abushakra, a former journalist, launched the initiative three years ago to tell the human stories that never make it into print. “On the one hand it’s nostalgic, on the other it brings really different people together,” she says.

The trend now in the capital is towards autobiographical storytelling. Dima Matta, a university professor and artist who launched storytelling community Cliffhangers in 2014, says that there is a need for it in the capital. “Stories bring people together. As humans we inherently love stories, we respond to them.”

In recent years, more women have taken to telling stories as well. “The term hakawatiye has been coined to name female storytellers,” Matta says.

Hakawati of the holy month

Back in Tripoli, it is past the end of Ramadan, when old traditions like the hakawati resurface for the holy month, but Kamareddine still has bookings in his diary. It’s no longer possible to earn a living this way so he also works as an actor.

It’s not just about entertainment - the duty of the hakawati is to 'fix the values in society' as one puts it

Kamareddine's fees - if it’s a paid job at a private venue or a public event sponsored by the municipality - are around $2,000, but he has a team to pay and demand is low. At smaller events the hakawati fee ranges from USD$50 to $300.

Listeners will have to come back for the ending when, after a life of heroic exploits, the low-born Antar “attained the chief desire of his heart” and marries his darling Abla, daughter of the king.

But just as the audience is straining to hear what comes next, Kamareddine shifts into a poem, closing the night’s chapter with lines that draw a moral lesson. It’s not just about entertainment - the duty of the hakawati is to “fix the values in society,” he says.

“My heart is at rest,” he tells their wedding guests. “Fortune has aided me, and my prosperity cleaves the veil of night.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.