Memories of displacement: Sudanese poet K. Eltinae on writing 'verses in the sky'

As a "

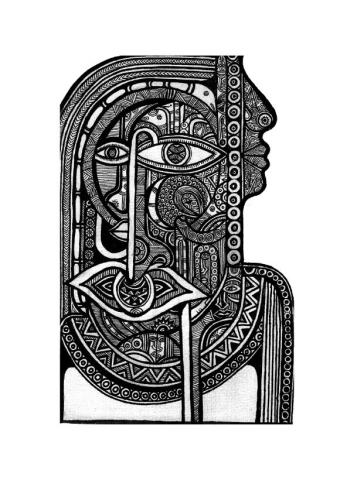

It looked like aimless doodling, but the shapes were actually letters. Eltinae was "writing verses in the sky," as he calls it.

"I wrote poems that made me laugh and look at the world in a way that made sense during times when I felt out of place in my own skin, culture, language and identity," he wrote in a recent autobiographical essay.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A Sudanese poet of Nubian descent, Eltinae grew up moving all around the world with his family, then to Khartoum in his late teens to study and later teach at the University of Khartoum before pursuing a higher education in France, Greece, and Italy, earning a triple masters in European Literary Cultures. He identifies principally as African, though he acknowledges the fact that he speaks Arabic.

Eltinae's work had appeared widely in print and online when his debut collection, The Moral Judgement of Butterflies, won the 2019 International Beverly Prize for Literature. It is due to be published by the London-based Blackspring Press this October.

According to the competition head judge, Todd Swift, the collection is "nearly faultless in its imaginative reach, creative flair, and astonishing versatility. It is exceptionally difficult to write beautifully, and intelligently, with complexity and yet sincerity, about issues of identity, society, and culture, and still avoid pitfalls."

In a poem titled Wasiya (meaning last testimony or will), Eltinae demonstrates all these qualities while imagining his own death in Exile:

that their tongues wrap around where I kept warm like a turban woven in prayer by strangers/ that I am not found stiff half hanging off a hotel bed under a phrasebook in another useless language.

'We were born to chase our truths in transit'

Eltinae attended American-system schools prior to living in Sudan, "which explains my accent," he tells MEE. He now lives in Granada, Spain, teaching English language and literature since 2012.

"We were born to chase our truths in transit," he writes in Tirhal, the poem that

Geographic rootlessness is one of several melancholy base notes the poems return to again and again, coming at it from a myriad of horizons, such as in this complex image from the book's final and longest poem, Butterflies:

At home, Sudan T. V. is blaring in the background with people dancing around whatever really needs to be said because people are way too polite to each other for no damn reason. I do not mention to anyone afterwards that I have been living in exile since I was eight.

After initially settling in Madrid in 2012, Eltinae moved to Granada where he sat down to write an episodic, autobiographical novel through which to make sense of his life.

The butterflies in the title of his collection are a

This brings to mind another profoundly displaced voice, the late San Francisco-based Iraqi poet Sargon Boulus, who wrote: "The butterfly that flies as if/ tied by an invisible thread to paradise

Whether explicitly or implicitly, i

In Kismet, an encounter with an elderly stranger at the airport prompts the verse "he could have been my father, with his blue-black skin/ asking directions in that language/ that wiped us off the map".

Writing from the personal

Eltinae, who is quite a private person, tells MEE he prefers to

In the poem, Breathing Exercises, for example, he openly addresses a relationship that triggers memories of displacement:

"I'm a goddess" you say, "I need a god" and all I can think of are my parents, those inshallah futures I cannot share with them because we are not the same people.

Eltinae manages to use specific experiences from

The poem Nefsi, for example (the word, also Arabic, means both "myself" and "I wish") is a litany of don'ts applicable to practically anyone:

You mustn't beg for love.

Wave it down for the rush it gives

or the places you discover together.

[...]

Never bow your head to loveless duties

those mirages you were taught to chase alone

while others walked their path.

Eltinae writes in English, the language in which he feels not so much at home as in control. But his poems contain the echoes and hues - syntactical, cultural and, in many cases here, experimentally typographical - of the languages he grew up speaking or feeling ancestrally connected with: Turkish, Greek, Arabic, Nubian.

Still, Eltinae has a strong, living connection with modern Arabic literature, which he reads in the original (two crucial texts for him are Tayeb Saleh's Season of Migration to the North and Naguib Mahfouz's Midaq Alley) as well as maintaining connections with Romance languages like Spanish and French.

Kohl, which is short enough to quote in full, recalls the music and the wit of Arabic poetry so closely it

Is it still called asylum?

when you race amid nightfall

setting camp under your own dust,

half dreaming you're a zebra

because the marrow in your bones

won't settle for a land?

And what about the fear

strangers paint across faces

whenever you cough or share a path?

Who will defend the maps

taken from the truth by lies?

Who will trace the kohl for our eyes?

Global literary influences

In addition to Arab writers, Eltinae's vision benefits from a wide range of sources. In terms of literature, he is quick to cite the great Farsi poets Saadi Shirazi and Hafez, as well as Rumi and Jibran Khalil Jibran.

And many of his poems do achieve the kind of simplicity and power that have turned the work of these poets into some of the most popular in any language. But Eltinae also has all the technical and contemporary edge you'd expect of high-brow poetry that might not be as popular.

He also draws on more modern influences, such as US poets Sylvia Plath, Diane Wakoski and Robert Lowell, as well as the Anglo-American poet WH Auden, whose The Age of Anxiety, a long poem in six parts first published in 1947, Eltinae says is the kind of poetry "that pulls me out of my life". He is also inspired by the emotional draw of the Alexandrine-Greek poet CP Cavafy as well as the work of Yiannis Ritsos.

Audre Lorde, from which he takes the book's breathtaking epigraph - "There is no place that cannot be home, nor is" - provides a model of social-justice writing in her essays and poems about race and gender that shows literary as well as ethical integrity, complexity and nuance, alongside commitment. Reading Lorde, he says, "feels like someone punched you in the gut".

More than anything, though, he stresses the eye-opening experience that came with reading Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things, which uses English to convincingly depict family and caste issues in southern India, a social and cultural landscape wholly distinct from anything previously experienced in the English language.

"I was like, wow, this is so beautiful how she managed to translate a totally different culture. This translating between worlds. It was what I needed to do," he says.

But his deepest guides may not be literary at all. The more you read of Eltinae's writing, indeed, the more the idea of "writing verses in the sky" resonates. Another motif that permeates Eltinae's poems is the collective injustice that goes beyond his experience as an individual of colonialism, racism, displacement and the Nubian exodus from Aswan:

Ninety thousand men, women and children

dragged their dust to rivers,

dams were never built for.

Under six cataracts lie the bones of my ancestors

Slaves, because the sun charred their skin

and made raisins of their hearts.

"You’ll see maybe there are these two voices in it," Eltinae says of his debut collection. "One that is more like an ancestral voice, and another that is definitely here and now, more revelatory."

But, while this backdrop ebbs and flows, it is the mysterious, private fracas - binding both voices and turning them into something universal - that proves most compelling. In one of several untitled fragments in the book he writes:

I find a terrace seat at a neighboring cafe, and begin drawing a line of pyramids in gold first, then purple, and black, before a friendly waiter takes my order. When he returns he asks if I'm drawing a fence or a border; I decide it's best not to tell him I'm drawing home.

The Moral Judgement of Butterflies, by K Eltinae, is available for pre-order from Black Spring Press

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.