Review: Reclaiming Syrian prison literature

In 2010, months before the start of the Syrian Revolution, a group of anonymous filmmakers in Damascus established what would become the world-celebrated collection Abounaddara, or The Man with Glasses.

The filmmakers' message was simple: they argued for a right that is not included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights - the “right to the image”.

For the collective, any representation of human suffering is a political and ethical choice and subjects of human rights abuses who are portrayed without a voice are stripped of dignity.

Most sensational perhaps is the viral image of Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi, whose lifeless body was pictured lying face down on a Turkish beach in 2015. His family requested that the media stop using the image, which the filmmakers suggest is a human rights violation.

Their videos addressing issues of detention and torture in Syria took on a more pronounced urgency once the uprising erupted.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Amid heavy mainstream media coverage of the war, including images of bombarded cities, miserable refugee camps and emaciated bodies, the collective aimed to break through the cacophony of reporting on the conflict and its atrocities by shifting attention onto individuals.

Coining the phrase "emergency cinema", they produced short, weekly “bullet films", satirising facets of the contemporary Syrian experience with topics such as revolution, displacement, censorship and resistance to religious extremism.

At first glance, the films, and in particular the series Saydnaya Prison: As Narrated by the Syrian Who Wanted the Revolution, appear to criticise the international human rights system that has failed to both prevent atrocities perpetrated by the Assad regime and find a resolution to arguably the greatest humanitarian catastrophe of our time.

Yet beyond the indictment, what the filmmakers actually do is call for a shift in thinking when it comes to understanding what constitutes a human right in the international community. Those involved aim to force advocates of international human rights law to contend with their occasional problematic and sweeping documentation of human rights abuses that exclude the subject from the report.

The film is one example of many from the body of Syrian prison literature that Shareah Taleghani analyses in her new book, Readings in Syrian Prison Literature: The Poetics of Human Rights - the most comprehensive of its kind to deal with the treatment of human rights and Syrian prison literature.

Iraqi novelist and literary translator Sinan Antoon said in a webinar on 26 February that the masterful work would be “required reading for anyone interested in modern Arabic literature, but also all those interested in the notion of human rights, especially in the Global South”.

Inspiration behind 'The Poetics of Human Rights'

Taleghani, an Iranian-American assistant professor of Middle East studies at Queens College, City University of New York, first became interested in human rights in high school, when she thought about becoming an activist or lawyer. Yet in the wake of 9/11 and the US government’s exploitation of the term under the guise of the so-called “war on terror”, she became more sceptical and began developing a strong critique of the West’s hypocritical discourse on human rights.

It was a graduate class at New York University with the celebrated Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury which sparked her interest in the genre of Syrian prison literature.

Syrian studies in English was and still remains a largely understudied field and the corpus of Syrian prison literature has largely been neglected in English-language scholarship. Prior to 2011, only a few works had been translated, including those by well-known Syrian writers and poets, such as Zakariyya Tamir, Nizar Qabbani and Hanna Mina.

During her research, she found that Arab literary critics had made the connection between prison literature and human rights discourse before the emergence of the subfield of literature and human rights in the US after 9/11.

It was then that she started a collective translation project, suggested by the poet Ammiel Alcalay and encouraged by Khoury, of Faraj Bayrakdar’s Hamama Mutalqat al-Jinahayn (A Dove in Free Flight). From that original source of inspiration, she continued to study works about detention.

Taleghani’s book is academic in nature, drawing on genre theory and critical and human rights theory, but also aimed at a more general audience.

The author is explicitly clear in the introduction of the limits of her work. It is not a history of Syrian prisons or human rights movements in Syria.

Rather, she pursues two questions: “What can we learn by reading Syrian prison literature, and what can Syrian prison literature teach us about humanity and human rights?”

Whereas most English-language scholarship on the intersection of literature and human rights has focused on the novel or memoir, Taleghani grapples with other genres, such as the short story and poetry, and how authors experiment with literary form to depict the experience of detention and the detainee as a speaking subject.

Organised thematically, chapters include the genre of prison literature as a problematic construction, vulnerability and recognition, representations of torture, depictions of prison space and life, and the relationship between carceral metafiction and exile. There is also a separate chapter on the notorious Tadmur Military Prison in Palmyra, and a coda that coalesces these issues and provides an answer to her two initial inquiries.

'Adab al-sujun': a problematic term?

Prison literature and prison writers are certainly not confined to Syria, the Arab world or the Middle East. In the Anglo-American context, works written from the perspective of the prisoner are categorised as prison literature.

As the scholar Dylan Rodriguez argues in examining the writings of imprisoned radical US intellectuals, the term has often been commercialised and aimed at a certain liberal readership. Using the term “prison literature” reproduces the hegemonic disciplinary regimen of the regime, because by defining the work as prison writing, as opposed to using a more general modifier such as literature, the term becomes homogenising and limiting.

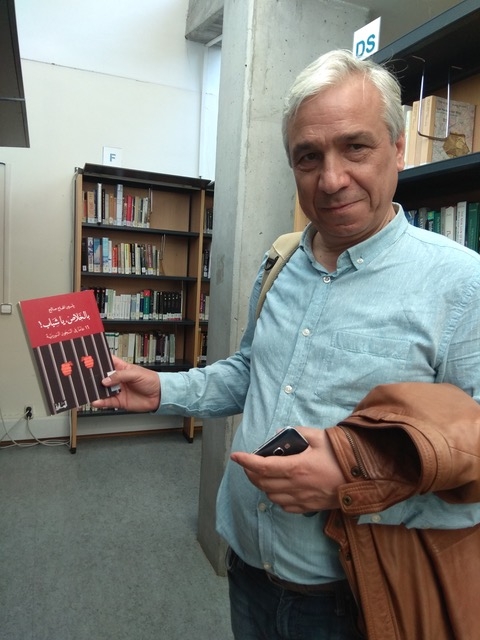

Indeed, some Syrian authors who wrote literature in prison reject the label in their works. Take prominent Marxist dissident intellectual Yassin al-Haj Saleh, who eschews the term in his introduction to Salvation, O Boys: 16 Years in Syrian Prisons because of its autobiographical nature. Rather, he relates the term to fictional prose works - works such as Mustafa Khalifa’s The Shell (al-Qawqa'a) or the short stories of Jamil Hatmal.

Other authors, such as Faraj Bayraqdar, consider their memoirs as part of adab al-sujun (prison literature) but are more concerned when the label of prison literature is applied to other works they produced in prison, such as poetry, that might not directly represent the experience of detention. Like prison literature or prison writing in English, adab al-sujun is an ambiguous, amorphous genre in the Arabic literary field.

In an Arabic and Syrian context, many writers are imprisoned for explicitly political reasons, and the label comes as one that they themselves often choose. Therefore Taleghani ultimately clings onto the generic term as a political imperative within its broader Syrian context; a gesture aimed at paying respect to the creativity and agency of how many of the authors identify their own texts - especially in the absence of state-sponsored creative writing and education programmes inside Middle East prisons.

Conventions and limits of human rights discourse

A cursory reader might accuse Taleghani of criticising international human rights organisations, but this is far from the case. Instead, her critique is far more nuanced, aimed at the system, language and discourse of human rights, which rights organisations have no option but to work in, with and through.

In her critique, she follows other scholars’ leads to acknowledge the power imbalances built into the system that need to be rectified, particularly the notion that the nation-state is the presumed protector of human rights. She argues that it is also an entity that can perpetrate the most pervasive human rights abuses (a point raised by Hannah Arendt even before the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights was created in 1948).

In tracing the histories of human rights, Taleghani reveals the way in which the modern concept came about being a complex one, with many influences, including works of literature.

The point she makes is convincing, argued through a close reading of literary texts in tandem with human rights reports. When human rights reportage excludes individual voices who are the survivors and victims of abuses from its narratives, it makes it easier for those with the authority to take action to ignore those abuses.

When human rights reportage excludes individual voices who are the survivors and victims of abuses from its narratives, it makes it easier for those with the authority to take action to ignore those abuses

While this happens only occasionally, when it does, those who are supposed to listen to such reports are less inclined to act on them because the erasures create a greater distance between themselves and the survivors they are reading about. An example of this was the Caesar photographs - images of people who had been tortured, starved and maimed while in detention, which were then displayed at the UN and the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Whereas some scholars who are critical of the concept and system of human rights have argued that the system should be disbanded entirely, Taleghani pushes back and asks: where does this leave those who continue to fight for their rights?

The argument, says Taleghani, is very easy to make when you are not the one facing violence, oppression and potential death. In addition, she recognises the important work of determined activists, including Mansour Omari, Mazen Darwish, the still unaccounted for Douma Four (Samira al-Khalil, Razan Zeitouneh, Wa’il Hamada and Nazim Hamadi), and countless others.

After all, the only way we know about the abuses and atrocities perpetrated in Syria and around the world is because of the work of grassroots human-rights organisations documenting, gathering evidence and taking testimonies.

At the same time, Taleghani does not think that any system or concept should be immune from criticism. Human rights are a constructed concept and system, and as such, they have the potential to be reconstructed. The system can be reformed, reinvented, made more effective and reconceived in and through a more truly global framework, and those changes can and must come from a global grassroots activist level.

The system we have does work and is successful in particular cases: for example, the recent trials in Germany of those suspected of abuses in Syria or active international campaigns for the release of individual detainees. For some, this may sound naive and impossibly idealistic, but Taleghani follows the lead of several of the Syrian authors whose work both echoes and challenges the generic conventions and limitations of human rights discourse and tries to side with the aspirational and the hopeful.

It is for this reason that this study’s long-term value is essential and intangible. Syrian literature, we are told, can teach readers a lot about how victims can retain their dignity and impact how we think about and reconceive human rights.

For emerging scholars in the field of Arab studies, many more histories and stories within and beyond prison literature are waiting to be studied, translated and disseminated to a global audience.

In such bleak political times on a global scale, we are encouraged by Taleghani’s inventive, systematic and scrupulous handling of Syrian prison literature and human rights. She can help us to open our horizons and rethink human rights - and emphasise the "human" in human rights discourse.

Readings in Syrian Prison Literature: The Poetics of Human Rights by Shareah Taleghani is available from June 2021 and is published by Syracuse University Press

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.