Ghosts of Thessaloniki: How a quest for a table revealed much about a city's multilayered past

Amber beads dangle from shop windows. My eyes dart from crucifixes and menorahs to a scale marked with okkas, the Ottoman weight unit. I dodge a line of bedsheets, distracted by the moustachioed face of a Greek Rebetiko singer - a crooner of songs about hashish and camel caravans - on an old vinyl record.

I am in Thessaloniki, Greece’s second-largest city. I have worked my way through the buzz of Aristotelous Square and a sprawl of concrete apartment blocks to Tositsa street, home to Bit Bazaar.

At night students flock to Ouzeris to snack on meze. I came on a late winter morning when the antique shops are open.

Before arriving, I had combed Etsy for a folding table and tray; the kind seen in black-and-white photographs of salons in the Ottoman Empire.

It didn’t take long for Google’s algorithms to register my search history. I was deluged with ads for sumptuously labelled Vintage Moroccan or Oriental Syro-Lebanese tables.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But I was due to visit Thessaloniki and wanted to score one from Bit Bazaar, in a city once known as “Jerusalem of the Balkans", but more recently, “Ftokhomana”, mother of the poor.

The table I discovered was caught up in the transformations that swept the city, leading to the chasm between those two nicknames.

Jerusalem of the Balkans

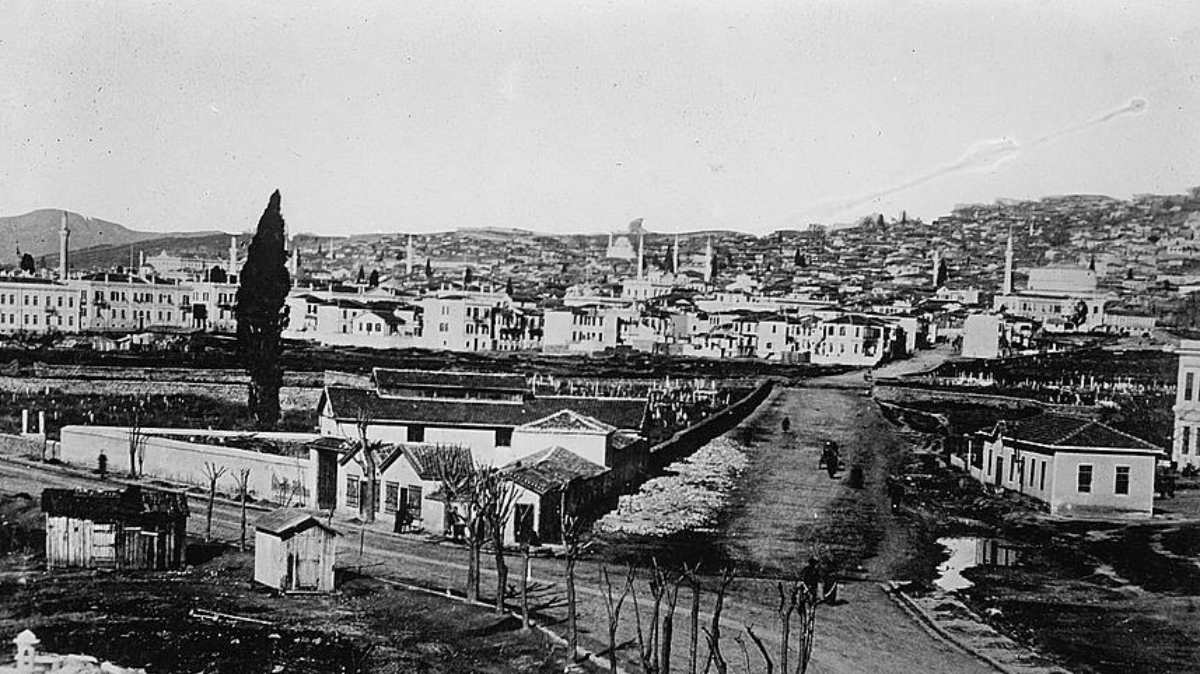

“A beautiful day in May, lovely sunshine, clear sky,” is how French writer Pierre Loti introduces Thessaloniki, known as Salonica during Ottoman times, in Aziyade, the quintessential orientalist novel.

The Salonica of 1876 that Loti chose as the backdrop to start the story of his secretive affair with a Circassian harem girl is an Aegean entrepot.

Loti strolls across Salonica’s “entire crazy city of oriental bazaars and mosques” as a “well-dressed Albanian [with] beautiful weapons”. He spends nights engaged in “bizarre prostitution” and afternoons at port-side cafes where customers order “hookahs, Skyros wine, Turkish delight, and raki”.

Aziyade is full of the tropes that western Europeans used at the time to describe their interactions with the Near East, but it provides a rich, first-hand account of the Ottoman's last great urban centre in Europe (Loti was stationed in Salonica as a naval officer).

'The Salonican quickly realised the westerners' weakness for souvenirs'

Macedonia: A Plea for the Primitive, A Goff and Hugh A Fawcett

Even before the Ottomans, Thessaloniki, the centre of Macedonia, a historic region which today encompasses parts of Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, North Macedonia and Albania, was poised between East and West.

Paul the Apostle stopped in Thessaloniki during the Roman period. After the fall of Rome, Thessaloniki was second only to Constantinople in the Byzantine Empire. Attacked by Avars, Slavs, Arab raiders and Crusaders, it was finally captured by the Ottomans in 1430.

At the time of Loti’s writing, Salonica was dubbed "Jerusalem of the Balkans", with a mixed population of Greek Orthodox Christians, Bulgarians, Muslim Turks, and Jews. In fact, Ladino-speaking Jews made up the majority of Salonica's inhabitants on the eve of the First World War.

I knew that Bit Bazaar was a repository of that past, but was sceptical if I would find the table.

Thessaloniki's skyline is no longer dotted with minarets and the few gems of Ottoman-era bazaars, open markets, and soft-hued, art deco buildings are now sandwiched between water-stained polykatoikia (post-war apartments).

My first attempt at finding the table was discouraging. At the first shop I asked in broken Greek if they had a trapezaki kai sini, or little table and tray, using the old Greek word for tray that is shared across Turkish, Arabic and Persian languages.

The shopkeeper shrugged me off.

A stash of sini were displayed face up outside the shop next door. This was more promising. The shopkeeper here was more friendly. These were about 80 years old he said, but ones inside dated back to the 18th century. I told him I was also looking for the table.

“Ahh, Arabica style,” he said, looking at a picture on my iPhone. “Dyskolo.” Difficult.

In the next shop, long-handled briki for brewing Turkish coffee lined shelves alongside crystal glassware. I soaked up the smell of cigarettes and incense.

The pickings were meagre compared to the last shop, but I found a copper sini I liked and asked the shopkeeper, who introduced himself as Christos, if he had a stand.

No sooner had he ducked out of the store than I was inspecting the tray atop a rich, almost ebony-coloured wooden stand. The delicate lattice blocs of mashrabiya were coated in a thick layer of dust and the legs were inlaid with mother of pearl.

Christos’ price: 100 euros with cash or 130 with card. Without bargaining, I pulled two crisp fifty euro notes from my pocket and headed north up Venizelou Street with my new table in the direction of Ano Poli, the old Muslim quarter of the city.

Ano Poli sits on a hill behind the old Ottoman konak, which now houses Greece’s Ministry of Macedonia and Thrace. It was spared the worst of the 1917 fire that ravaged the centre of the city. Its cobblestone streets are flanked by Ottoman era houses with sachnisi, jutting bay windows, and mandarin tree scented gardens, which are squeezed awkwardly between parking lots.

I’m meeting friends at Tsinari, a glass-paned, Ottoman-era cafe to celebrate my find. We order beetroot salad topped with chunks of garlic, stuffed grape leaves and tzigerosarmas, liver and rice wrapped in intestine. The Macedonian winter’s chill is doused by the cast-iron stove and sips of fiery tsipouro, a Greek spirit.

Here were East and West mixing at their finest, I thought to myself, riding high having discovered the table at Bit Bazaar, and capturing my own slice of the city's past.

“The table isn’t Greek you know,” a friend said. “It’s Islamic. It doesn’t have anything to do with Thessaloniki.”

Another needled me with laughter. “Μalaka,” Greek slang for idiot. “My grandma had these trays for pitas (pies). It’s very chorio (village). No one wants this stuff.”

'Whiff of modern-day Byzantium'

In Salonica City of Ghosts, the historian Mark Mazower remarks how late Ottoman Salonica was Western Europe’s window into the Orient, increasingly typecast by writers like Loti:

“As Athens and Belgrade erased the traces of their recent Ottoman past, Salonica was turning into nothing more than a style - an 'unmistakably Eastern look' - which became ever more pronounced… its anomalous character in a European setting ever more seductive.”

'There was a to-ing and fro-ing of fashion and tastes in sophisticated cities like Salonica. A house would mix Oriental and European furniture'

George Manginis, academic director, Benaki Museum

For me, there is a whiff of modern-day Byzantium to Thessaloniki, where the girls wear more make-up and the men dress more tough than in Athens. The pull of the Orthodox Church is stronger here. Thessaloniki is 130 kilometers from Mount Athos. Modern borders haven’t stopped Turkish, Greek and Bulgarian cuisines from mingling in the city.

“Thessaloniki is seen as the heir to Constantinople in Greek culture because of the church and descendants of Asia Minor refugees,” Basil Gounaris, an expert on Modern Greek history at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki told me.

“But it’s not a great port city any more. People travel by aeroplane. Not steamship”

Christos told me the table was at least 100 years old. “Thessaloniki was a centre for trade in the Mediterranean,” he said. “At Bit Bazaar we see antiques from everywhere - Bulgaria, Turkey, and Egypt.”

My impression of a continuum between this past and contemporary Thessaloniki inspired my hunt for the table. But had I fallen into a trap of writers like Loti, seeing only the culture and history I wanted to, and imposing a connection that no longer existed.

I wanted to find out more about my new table and its place in Salonica.

‘Turkish swords and Greek daggers’

“The Salonican quickly realised the westerners’ weakness for souvenirs,” according to A Goff and Hugh A Fawcett, the authors of Macedonia: A Plea for the Primitive, which was published in 1921.

Tourists in Thessaloniki at that time had their pick of “antiques, such as Turkish swords and pistols, Greek daggers, Albanian cartridge cases and old coins dating from the Byzantine and Roman eras”.

Clearly, I wasn’t the only one lured to the city's curiosity shops. By the Ottoman Empire’s dying days, Salonica, like the port cities of Beirut and Smyrna, was readily accessible to westerners.

Mercedes Volait, an expert on oriental antiques and design at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, said my table would have fit right in at Salonica's shops, geared to westerners on grand tours of the Near East.

Based on the photos I sent her, Volait said my table was built in the late 19th century in Damascus by the Arouani family, Syrian Christians who owned a firm manufacturing “Levantine” style furniture.

“Tables like this were circulating around the Eastern Mediterranean. Dealers in Cairo and Athens had them,” she said. “They are a 19th century invention. Before that, we know that in Damascus, for example, people didn’t have tables. The idea of spending money on something like this was very recent.”

Accounts of the Macedonian countryside at the time describe hardscrabble Muslim and Christian homes. In Athens, I visited George Manginis, academic director of the Benaki Museum, to ask who would have purchased my table.

“Tourists, of course,” Manginis told me, then smiled “And Levantines, who followed the European fashion for the Oriental, but understood it better than them because it was all around them and familiar.”

The Levantines were the multilingual merchants, bankers, diplomats and spies who kept trade and politics in the Eastern Mediterranean humming. They called cities like Salonica and Smyrna home and made their fortunes serving as intermediaries between East and West.

The Benaki art museum was founded by a Levantine, Greek Alexandrian businessman Antonis Benakis, an avid collector of Islamic and Oriental art.

“The middle class Levantines buying these tables were copying the great collectors like Antonis Benakis, who himself got the collecting bug from western Europeans. There was a to-ing and fro-ing of fashion and tastes in sophisticated cities like Salonica. A house would mix Oriental and European furniture, bourgeois Christians and Muslims alike.”

When A Plea for the Primitive was published, Thessaloniki was on the cusp of astonishing changes that would alter how locals interacted with “Levantine” products.

'Oriental aesthetic'

In 1912, Greek troops liberated Salonica from the Ottomans in the first Balkan War. Greece entered the First World War on the side of the Allied powers. At its conclusion, Greece was rewarded with a stake in Asia Minor, which was then home to more than a million Greeks.

Salonica-born Mustafa Kemal Ataturk led the fight against Greek troops after the First World War, expelling them from Anatolia and founding modern Turkey. Today, Mustafa Kemal’s house is a museum attached to the Turkish consulate.

The Greek defeat in Asia Minor culminated in the 1923 population exchange in which 1.5 million Greek Orthodox Christians were expelled from modern-day Turkey and 400,000 Muslims from Greece.

'Tables like this were circulating around the eastern Mediterranean. Dealers in Cairo and Athens had them'

Mercedes Volait, oriental antiques expert

Thessaloniki became home to many Greeks fleeing persecution in Anatolia. They settled in abandoned homes in Ano Poli and built Bit Bazaar, whose name comes from the Turkish word for lice.

The Second World War brought the final blow to Thessaloniki’s cosmopolitanism, when 96 percent of its 46,000-strong Jewish population were murdered in the Holocaust.

The Greek-Turkish war and population exchange dimmed the appeal of Levantine furniture among Thessaloniki's new Greek bourgeoise, Manginis said. “The landscape changed."

"What was an aesthetic, orientalist vision became politicised," he said. Tables like mine were discarded.

Still, Greece's upper class couldn't cut their cultural and geographic ties to the Near East.

Benakis, an ardent Greek nationalist, opened his museum in 1931 when the memory of the population exchange was still fresh. The bulk of his collection comprised Oriental art and antiques. “Benakis appreciated these things for what they are, beautiful items, part of our region's history. He didn’t put political labels on them," Manginis said.

More recently, Thessaloniki’s former leftist mayor, Yiannis Boutaris, made a push to promote the city’s cosmopolitan past, hosting art exhibitions in the remaining Ottoman and Jewish landmarks and pitching the city to Israeli and Turkish tourists.

My last call was to Brendan Lynch, the former head of Sotheby’s London Islamic Art department and an antiques dealer. He told me Greece was a go-to spot for Levantine collectables during the era of great Near Eastern tours. Today, prices for original items in Athens can rival London or New York.

“I guess Thessaloniki is still off the tourist map, at least in the winter,” he said. Lynch estimated the table’s auction value at $500-600. A handsome profit. The Levantines would be proud. But my table is not for sale.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.