White gold: Why Tunisians love floral waters

I don’t remember how old I was when I opened the kitchen cabinets at home and saw strange, worn-out plastic bottles lined up against the wall, filled with one of Tunisia’s treasures - traditional floral waters.

Typically made by women, the flowers used to make the liquid are harvested in the spring, when flowers are ready to be picked by hand.

The orange blossom (Citrus sinensis) season starts in April and May each year, followed by the rose season. Once the flowers are collected, no time is wasted in proceeding to the next step; the North African heat can fast deplete the flowers of their precious essence. Many, such as the dog rose (rosa canina), need to be handpicked at dawn and immediately sorted for quality, weighed, and distilled.

The steam distillation process for floral water involves extracting suspended essential oils and water-soluble volatile components using a double technique of heating and cooling.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The process is often done in the home, by women using a closed-circuit two-step tank, a device known as an alembic. In the first vessel, the flowers are slowly heated, then steam passes through cold water via a tube, which falls in drops into a second vessel, the fechka - a large glass receptacle, often an heirloom passed down from mother to daughter. The collected liquid serves as the floral water.

I remember seeing plenty of fechkas in my family’s house in Tunisia. As a child, I wasn’t allowed to touch them, because they were so valuable. I would watch my aunts pour a tiny amount of the liquid to use for their hair and skin, infusing the air with an unforgettable scent.

It’s hard to describe the aromatic intensity of such a harvest.

“You need to smell it to understand,” says Rania Mansour-Snoussi, a Tunisian artisanal flower distiller and founder of Ezemnia, in a short documentary for news outlet Brut. “The process can take hours.”

Ancient processes

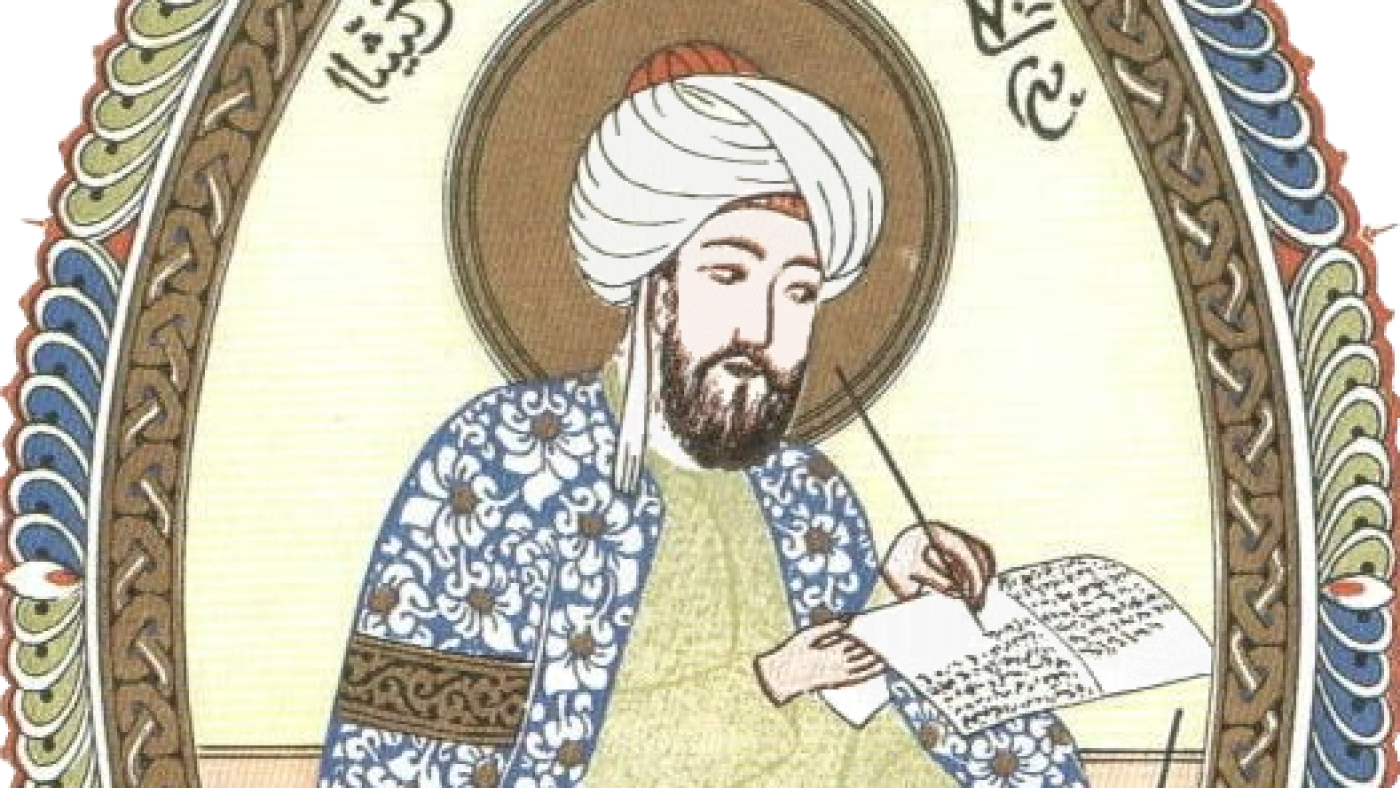

The process itself, with the use of alembic, harks back to ancient chemical experiments, Arab pharmacology, sciences, and alchemical pursuits.

As early as Mesopotamian times this mode of extraction was used to separate substances. Archaeologists have found ancient types of alembics in northern Iraq estimated to date from around BCE3500.

The Persian polymath Ibn Sina is credited with inventing modern steam distillation of essential oils, chiefly rose essential oil, during the 10th century. The second book of his highly influential Canon of Medicine details the purported medical virtues of key plants.

Physician and chemist Abu Bakr al-Razi, who would discover sulphuric acid and ethanol, wrote in his 10th-century text Book of Secrets (Kitab al-Asrar) about early distillation experiments and processes.

And in the 12th century, the Andalusian Ibn al-'Awwam's Book of Agriculture (Kitab al-filaha) described distilled herbs and plants that are still consumed today.

The 'smell of Tunisia'

A Tunisian pantry would include one or several of these floral waters to treat most common ailments, in addition to use in baking and cosmetics. It’s a basic pharmacy that families self-produced, before it became cheaper to buy ready-made. Some floral waters are now produced commercially for exports, including for the luxury perfume industry - neroli, an extract used in perfume production, is derived directly from orange blossom flowers.

Orange blossom water commonly treats stomach ailments, insomnia, anxiety, asthma and heat exhaustion. Because of its cooling effects, it’s a summertime favourite.

Over 2,500 tonnes of orange blossom were picked in Nabeul, along the northeastern Tunisian coast, in 2022 and 60 percent of this produce is distilled locally. Around 3,000 families in the region rely on the flower for their livelihoods.

Orange blossom water, or Tunisia’s “white gold”, is also a staple in desserts in Tunisia, and worldwide. It carries a distinctively delicate but bitter flavour.

In Nabeul and the Cap Bon region, from where most of the Tunisian floral tradition originates, and continues to thrive via small businesses and annual fairs, orange blossom is also used in the preparation of savoury meals. It mixes well with saffron and can be used to wet couscous grains and enhance the taste of local ragout. The Tunisian award-winning online food magazine Mangeons bien documents these various culinary uses, from strawberry salads to mesfouf, a rich couscous dish mixed with olive oil and butter.

Tharwa, a Tunisian student based in Rabat, Morocco, has fond memories of orange blossom water. “My grandfather used to spend summer evenings in his garden, where a delightful breeze came from the sea,” she says. “He would drink his Turkish coffee with two drops of zahr [orange blossom water]. Today I can still smell his coffee and remember how he told us stories from his youth.”

For Tharwa, who occasionally experiences homesickness, it’s the smell of home, the smell of Tunisia.

Zahr added to coffee is called “café blanc” and an adaptation of Levantine traditions. Besides orange blossom water, other common floral waters include various rose varieties, jasmine, mint, rosemary, thyme and geranium.

Rosa canina, known as nesri in Tunisian dialect, and rich in antioxidants, was introduced to the green slopes of Zaghouan in northern Tunisia by Muslim Andalusians following the Reconquista. An annual fair continues to celebrate the flower, which is considered good for the heart.

Thyme is often used to combat respiratory illnesses. Geranium water, called atarchya in Tunisian dialect, contains skin benefits and can be sipped with coffee. The cost of a litre of geranium water starts at around 10 dinars, a little over $3.

Healthcare costs and climate emergency

Residents of Tunis and its surrounding areas are familiar with the sellers of Souk el Blat, home to traditional herbalists.

Mourad Ben Cheikh Ahmed, the Tunisian urbex photographer and “medina explorer” behind the popular project “Lost in Tunis”, has often visited Souk el Blat. “I love going there to smell the plants, see their colours, read the strange names, and for the photo-worthy potential of the place,” said Ahmed, who also goes by the alias Dismalden online.

Many such shops have closed, replaced by shops selling imported goods and other “fakes”, which are likely to be more lucrative.

The popularity of traditional remedies reflects a growing interest in alternative medicine such as phytotherapy, especially for the urban, educated, and well-off. But it also sheds light on a bleaker reality and economic hardships. Corruption, the exodus of medical personnel, the stress of the ongoing pandemic on a fragile health system and territorial inequalities mean that Tunisian households spend over 35 percent of their income on healthcare, according to the World Health Organization.

Rising medical costs in the formal health sector contribute to vulnerable families often resorting to cheaper options, such as herbal medicine.

Floral or aromatic waters are less concentrated than essential oils, and for this reason gentler for use on the skin, including children’s. But they are more fragile and degrade faster. They are also seasonal, generating one annual harvest. A tonne of orange blossom flowers can yield 600 litres of orange blossom water, a ratio that can vary according to different flowers used.

As accelerated climate change further disrupts weather patterns and access to water, artisanal modes of production will need greater protection to ensure they preserve local traditions and remain a unifying pride of Tunisian culture.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.