Letters of Refuge: Messages home, from ancient Gaul to modern Calais

In September 2022, a 17-year-old boy from northeast Africa walked into the Secours Catholique day centre in Calais.

Arriving with a group of friends, he was one of between 500 and 700 migrants and refugees to go to the centre that day.

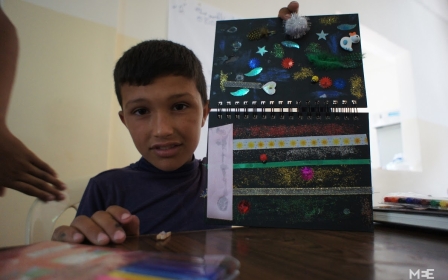

He went out into a courtyard, where the charity Art Refuge had set up a table full of typewriters on which the refugees could write to whoever they wanted.

The boy sat down and started writing a letter. “Dear Moma,” he typed, “I send you a lot of my love and I miss you so much, you and my brothers. How are you? Since I left, I have been thinking about you.”

The 17-year-old had heard some news and he wasn’t quite sure what to do, or whether to believe it. “I miss my dad,” he wrote. “I miss my dad and he passed away. I didn’t believe it until now so every day in the night I think about him and my brothers without him. I love you all and I miss my friends.”

When he arrived in Europe, in Malta, he didn’t like it, because the people were “not friendly”. In Calais, with the community he had found at the day centre, he felt “happy and comfortable”.

“I like writing letters and that is my new hobby,” he told his mother. He cast his eyes to the future. He hoped to go to England, a journey from the shores of northern France that can now only really be taken on the “small boats” targeted by the British government.

‘Community table’

On the ground floor of Bush House, once the central London home of the BBC’s World Service, this letter sits alongside others both ancient and modern, as part of the exhibition Letters of Refuge, a collaboration between Art Refuge and King’s College London.

In one room there are typewriters used by migrants and refugees last year to write letters at Art Refuge’s “Community Table” in Calais and Folkestone, a regular landing site for those who arrive by boat on England’s south coast. These can be seen - and used.

The charity, which is run by artists and art therapists, has been working in Calais since 2015 and in Folkestone since the beginning of the Covid pandemic.

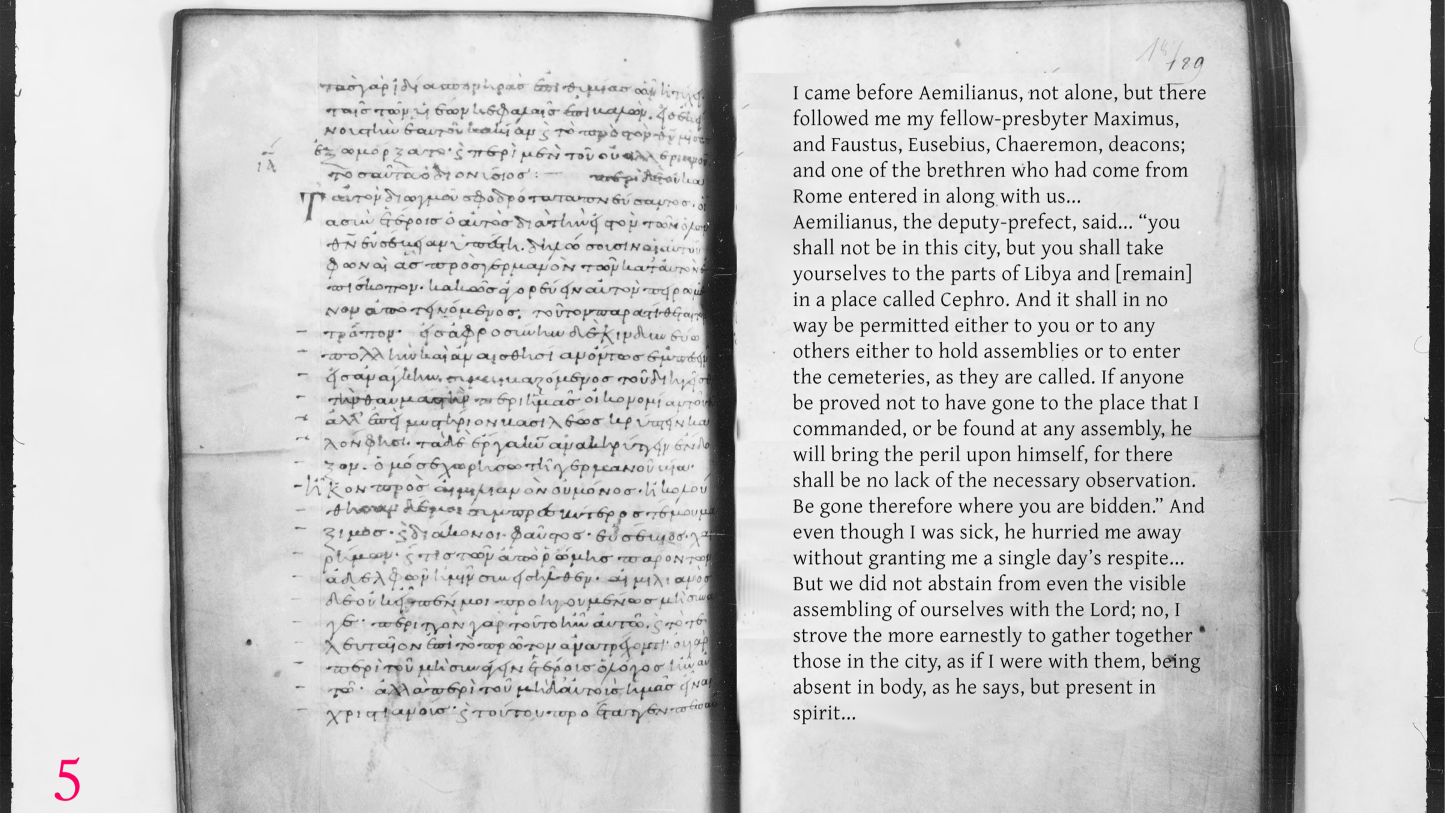

In another room, the contemporary letters on one wall are juxtaposed with letters written by early Christians who found themselves persecuted or displaced within the Roman Empire.

The effect is to create a dialogue between the two, so that the voices of the dispossessed speak to each other across a period of 2,000 years.

In one place, these voices, turned into poems, can be listened to, alongside newly commissioned artwork that shows the routes taken from North Africa and the Middle East into Europe.

Ancient and modern experiences

The exhibition is timely. The British government’s asylum bill, which the United Nations has called a “clear breach” of international law, seeks to detain for 28 days anyone who arrives in Britain by an “irregular route”.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has spoken at podiums adorned with the words “Stop the boats” and Home Secretary Suella Braverman has just been to Rwanda to cement a deal to deport migrants to the east African country.

“We are not hearing from the people impacted,” James Corke-Webster, co-director of the Centre for Late Antique and Medieval Studies at King’s College London, told Middle East Eye, sitting in the cafe that adjoins the exhibition space.

“We are hearing from the government, from Gary Lineker and the BBC. In the ancient world, the voices of those impacted were also lost.”

Corke-Webster’s work focuses on the early Christian communities that provide the ancient letters featured alongside the work of today’s exiles and refugees.

“What’s striking is the extraordinary parallels between the ancient and the modern experiences,” he said. “Law and policy often envisage faceless, silent categories, but this is an issue where it’s vital to remember that those laws and policies impact on people - people who not only have voices, but voices that remind us of the ubiquity and commonality of what they have endured.”

Papyri that have survived from Egypt because of the hot, dry weather show endless numbers of petitions written from the provinces to those in power. Corke-Webster says that the local issues documented - this man stole my sheep, but that man stole my wife - were actually often the trigger for the persecution of minorities because the law was then weaponised against them.

If Christians or other minority groups across the vast Roman empire - which included large parts of North Africa, western and northern Europe and the Middle East - rebelled, then the “Roman state would be quite violent… They have an empire in order to bring money to the centre. They only intervene in the provinces to shut down social unrest.”

Letters, both ancient and modern, are usually concerned with loved ones. In the collection of modern communiques, there is one to the author’s sister, in which he says, “I want us to grow up together”.

There is a dispatch from an Afghan refugee back to his “comrades in Afghanistan”, saying that they could never have imagined that “local politicians in government with the help of the Taliban” would have scattered them to the winds.

‘Like beasts against us’

In one of the ancient letters, Dionysius, a resident of Alexandria in Egypt, writes from exile in Libya, “in a place called Cephro”. He struggles with the loss of community, something that afflicted many Christians in exile under the Romans.

Perpetua, in prison on account of her religion, is detained with her baby, like a young mother sitting in a British detention centre or hotel waiting for her asylum claim to be processed.

In the late second century CE, a group of exiled Christians in the French towns of Lyons and Vienne, in what was the Roman province of Gaul, write home to Asia Minor, describing their experience of what sounds like a pogrom.

'We were even forbidden to be seen at all in any place whatever'

- From a letter by persecuted Roman Christians

“The greatness of the persecution here, and the terrible rage of the heathen… are more than we can narrate accurately,” they write.

“We were not merely excluded from houses and baths and markets, but we were even forbidden to be seen at all in any place whatever... all men turned like beasts against us, so that even if any had formerly been lenient for friendship’s sake, they then became furious and raged against us.”

Once again, we only have to look to modern day Britain for a clear comparison, with far-right activists attacking and abusing asylum seekers outside the hotels they are being housed in.

Against this, there are hymns to the good work done by those looking to help migrants and refugees. Mansoor, in a letter from last year, writes to “the people from different countries seeking asylum in the United Kingdom”. He hails those in “volunteer jobs who show solidarity with us that our dreams matter” and ends by saying that “wherever we find justice that’s our country”.

There are lighter letters. One is a note to the late British scientist Stephen Hawking, written in pen and ink: “I just want to let you know, I think I have discovered the theory of time travel and multiple reality… All we need is strong memory, brain and camera. That’s it. Enjoy your time in the city of stars.”

An ancient petition to the Roman emperor comes from Justin, living in the second century in Neapolis (modern day Nablus) in the province of Syria Palaestina. He writes “on behalf of a group… drawn from every race of human beings, who are being unjustly hated and abused”.

His modern-day echo comes in the form of a letter written in Calais to French President Emmanuel Macron. “Dear Macron,” it begins. “Why France government did not protect migrant? I am not happy… I love you Macron, please change the situation.”

In the end, what ties the letters together is what ties us all together: family, friends, homeland, community.

Across the centuries, there are words of hope, resistance and endurance in the face of power. “I’m OK, don’t worry about me,” one son writes to his mother. “Don’t worry, I am fine.”

Letters of Refuge runs until 24 March 2023 at The Arcade, King’s College London

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.