Plants of the Quran: London exhibition showcases Islam's botanical legacy

According to one hadith or saying attributed to the Prophet Muhammad: “If a Muslim plants a tree or sows seeds, and then a bird, or a person or an animal eats from it, it is regarded as a charitable gift for him."

A new exhibition at the Kew Garden's Shirley Sherwood Gallery started during the Islamic month of Ramadan and aims at showcasing the range of plant life mentioned in the Quran.

Dozens of plants are mentioned in the Islamic holy book but the terminology used in classical Arabic makes establishing their modern counterparts a challenge. (Lentils and a number of other paintings in the Shirley Sherwood Gallery in London - MEE/Alex MacDonald)

Artist Sue Wickison worked with Kew Garden scientist Shahina Ghazanfar to produce these new artworks, which involved extensive travel in the Middle East as well as meticulous botanical research.

Wickison said she was inspired by a visit to the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi and the floral patterns that adorned its floors. "It's quite different from the normal geometric shapes and being a botanical illustrator that's what attracted me. So, I started to investigate to see if there's any information about plants in the holy Quran and what the plants represented," she told Middle East Eye.

"At the time, I couldn't find very much about them so I contacted a colleague at the Royal Botanic Gardens to ask if he could recommend someone... Shahina actually had been researching for years and was writing The Plants of the Holy Quran. So, it was an amazing coincidence, I mean, serendipity." (Figs by Sue Wickison)

Ghazanfar's book Plants of the Quran, is set to be released in May 2023. She said there was a difference between the Arabic names for plants in the Quran and those used in modern Arabic.

"Research was quite difficult - there are only ten or 12 plants that are fruit plants, so they have classical Arabic names like the date palm, like grape or olive," she said. "Many of the other plants that are also mentioned in the Quran... we don't really know the context that they have been mentioned."

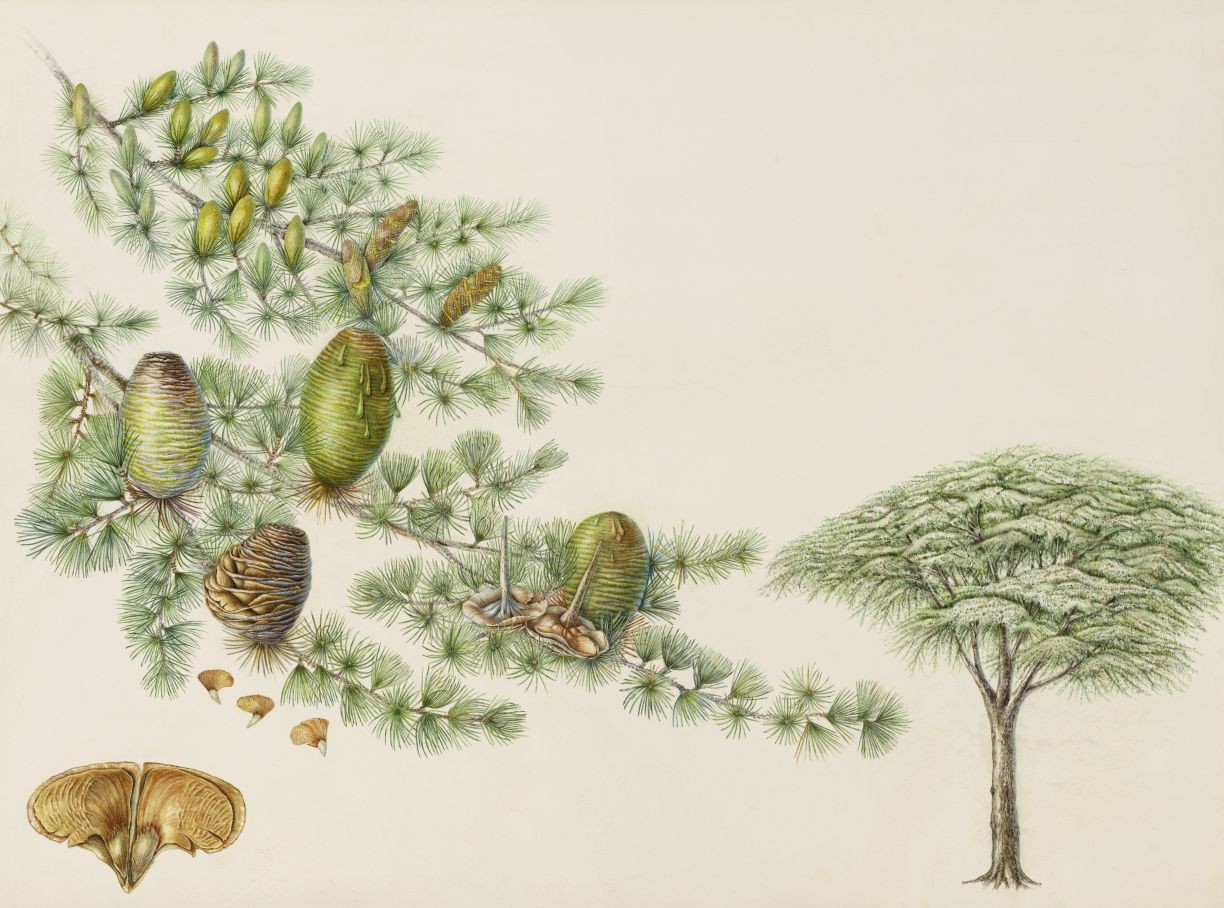

The researcher described looking back at ancient cuneiform texts, such as those in Akkadian or Sumerian, as well as Hebrew and Aramaic texts to see whether there were any similarities to the names used in Quranic Arabic. (Cedar of Lebanon by Sue Wickison)

Ghazanfar and Wickison travelled across the Middle East during their research, including to the UAE, Oman, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, as well as consulting a range of researchers in other countries.

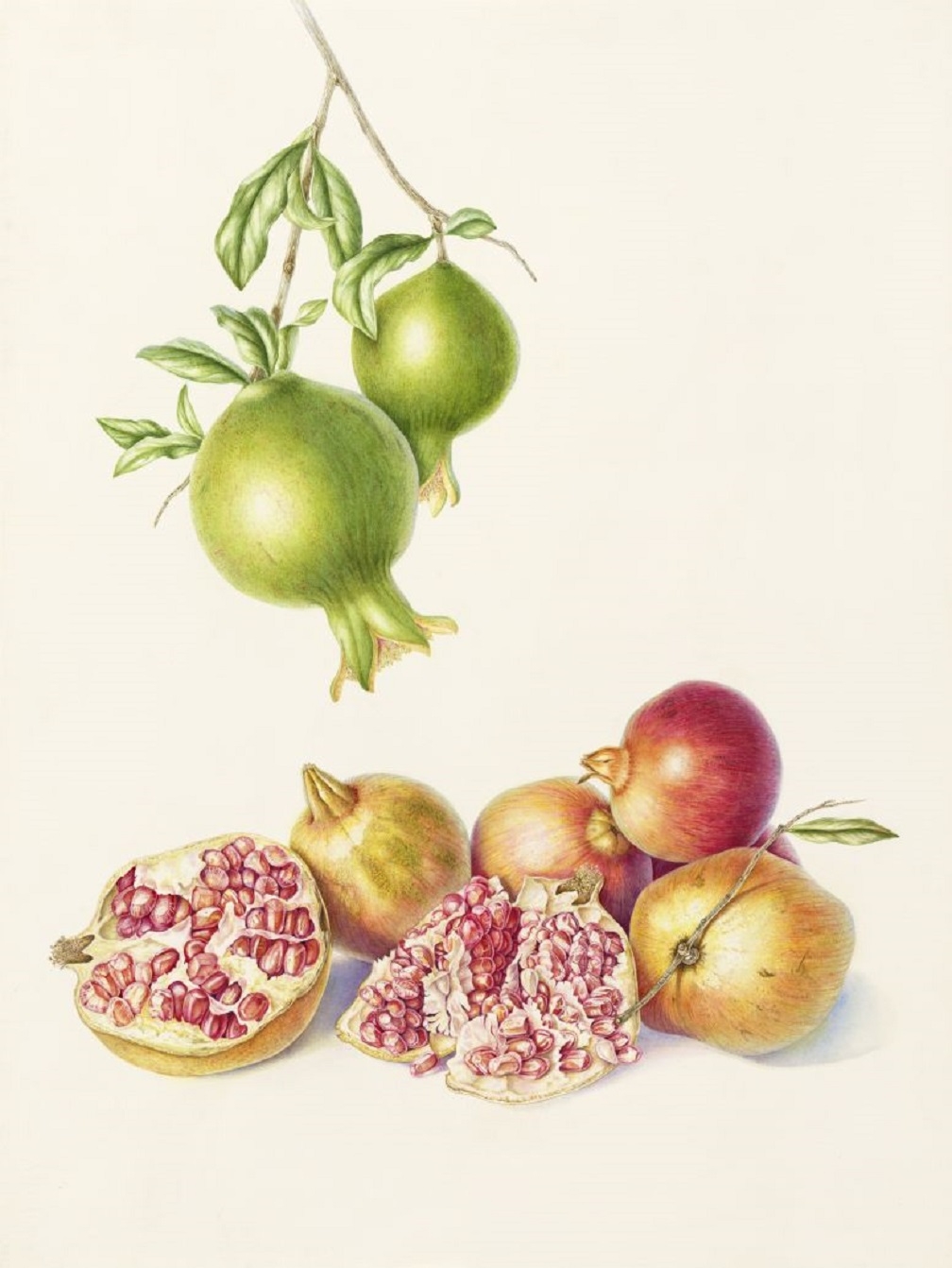

"I've been shown so many different varieties. So, it's not just the sort of brown onion you find in the supermarket, it's the round white one I saw in Oman and it's the different shapes [of onions] I've seen all across the Middle East," said Wickison. "I've been shown figs from Morocco, from Syria, from Palestine, from Lebanon, from Oman. So again, I'm trying to show a variety of different types."

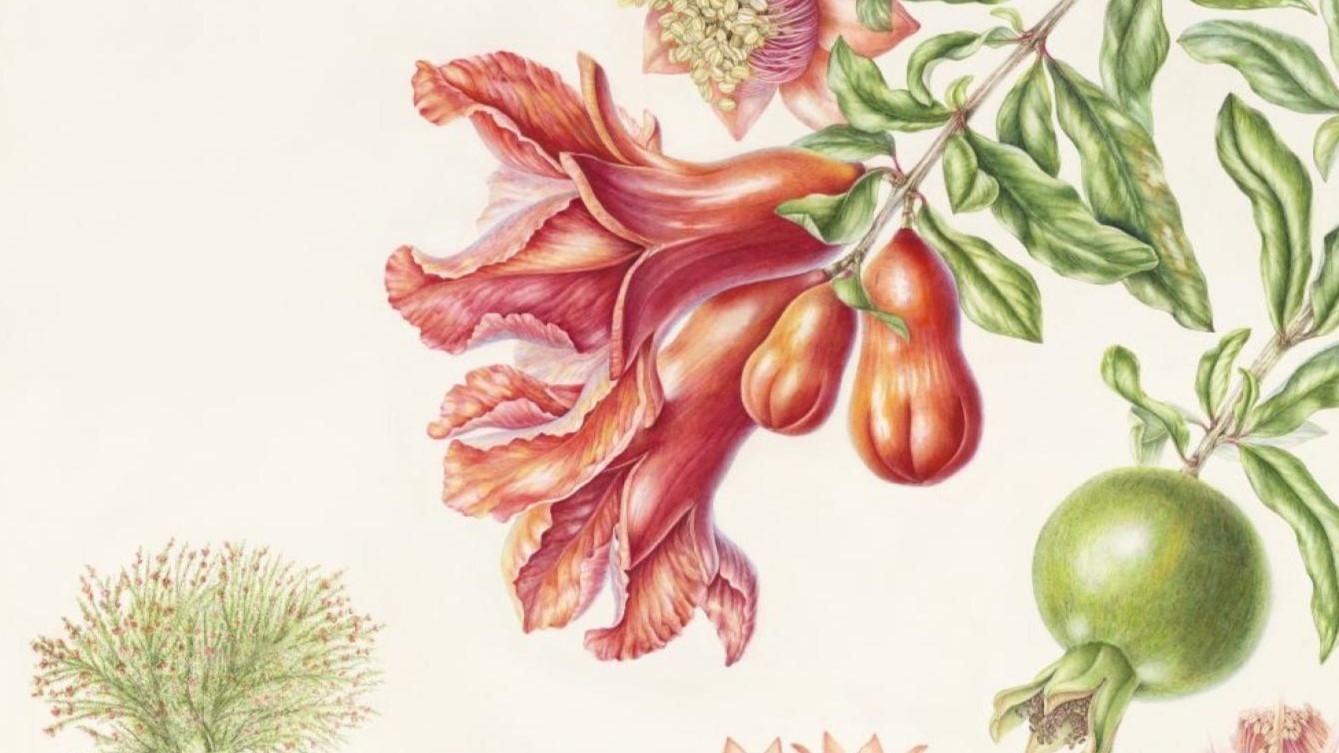

As a botanical illustrator, she said it was crucial to have fresh specimens, which she poured over, examined with microscopes, and dissected to get as much detail as possible. "The nature of my work is very meticulous," said Wickison. "I make a lot of cover notes, and apart from getting to understand the plant, it takes hundreds of hours of drawing and painting." (Toothbrush Tree by Sue Wickison)

While some of the Quranic references are clear - for example, olives are called "zaytoun" as they are in modern Arabic - some are more controversial. For example, "kafur" is mentioned once in the Quran, and in the exhibition it is linked with henna, still widely used as a dye. But kafur could also refer to grape blossoms, or a sheath of palm tree pollen, while in some translations it refers to the wood of the camphor tree.

Ghazanfar said another tricky plant had been "yactin", which she understood to be a gourd. "That was a bit of a problem... for that, I met with a friend who was researching all the names," she said. "We looked at the different types of plants in the Bible, what it said in the Torah, and what it said in the Quran.

"So, in my book, I've included all the possible alternatives as well, because we still can't say with certainty that it is a particular plant. The word used in Palestine for a gourd is 'yactin' , but it isn't the word used elsewhere for the same plant." (The 'Ethiopian false banana' plant alongside other illustrations- MEE/Alex MacDonald)

All this research was a true journey of discovery for the researchers. Some of the details they came across would have been easily missed by the naked eye and Wickison was keen for her illustrations to include the finer, less obvious aspects of the plants.

"There was one particular plant, hamada, which was in the desert in Sharjah [in UAE]... I looked at it and I thought that the green stems didn't look very interesting," she said. "And then when I looked closer, under the microscope, I saw little tiny flowers one millimetre big. So, under the microscope is where I draw them. I enlarged them so people can also appreciate them. Because otherwise you just see a tiny stem and you don't realise what's there. By enlarging the plants, people are educated, and they see the beauty that I see. Once you get the plants under the microscope, it's a whole new world." (Pomegranate fruit by Sue Wickison)

All across the world, millions of Muslims will be waiting each day this month for the sun to set so they can break their fast with the evening iftar meal. And on their dining tables and in their restaurants, many of the plants featured in the Quran will still be a staple part of the meal, cementing a historical link with the past, and the lifestyles and societies that inspired the modern faith.

"One thing that has been incredible through the whole journey was the support that people have shown me in terms of their enthusiasm, encouragement, assistance, and interest in the project," said Wickison.

The researcher described meeting pomegranate farmers in Oman who were fascinated by the work she was doing and her reasons for visiting their country, even encouraging her to take specimens back to the UK with her. "It's been an incredible journey of cooperation and assistance," she said. (Armenian Cucumber by Sue Wickison)

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.