The Baba on your shoulder: Why more Arab-Americans should enter the arts

It started with a joke. It was one I’d heard before in different forms, but in February of 2020, the comedian Toufiluk tweeted it out in its most hilarious form to date:

Arab career options:

1) Doctor

2) Lawyer

3) Engineer

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

4) Disgrace to the family

That punchline resonated with me, as it did with so many children of Arab immigrants. It’s one of our “inside jokes” – as immediately understood as our common revulsion at the mention of red velvet hummus.

We all get it, because, like much good humour, it also puts the spotlight on a truth.

And yet, when I think of the joke, I also experience a feeling of regret. Why is it, I wonder, that more Arab Americans don't encourage their children to enter into fields like writing, the fine arts, acting, and other creative endeavours?

The fallback plan

I know that your baba (father) is shaking his head right now, saying: "Those careers don’t make money." I don’t mean your real baba, but the one in your imagination - you know, the one who sits on your shoulder and comments on your career choices and the people you date.

Or maybe this tiny baba is shrugging and saying: "If you like music, join a band… after your medical residency."

Or, "Yes! Write poetry, habibi … as soon as you pass the bar exam."

In fact, Arab parents would love for their children to excel in a lucrative, prestigious career and then also be successful in a creative side hobby. (Case in point: Toufiluk’s Twitter bio lists him as a "part-time comedian, part-time biomedical engineer.")

I get it. Many immigrants who come to the United States understand financial insecurity, and the bottom line is: they do not want their children to experience it. Nobody is better at creating a "fallback plan" than immigrants.

My own parents, when I announced in fourth grade that I wanted to be a writer, bought me a typewriter (it was the 80s, so yes, it was indeed a typewriter).

Years later, while I applied to colleges, they encouraged me to focus on building a teaching career, "in case publishing books is harder than you imagine." Fair enough.

'My folks always told us ‘Do what you love, that is more important than money.’ So, when I showed musical talent, they encouraged it'

- Dave Hall, composer

I’ve been a college English professor for over 20 years now, and my teaching enriches my life and writing in many ways. And they were right – the publishing industry has not been as receptive to Arab-American authors as I’d hoped. Furthermore, my parents continue to be as supportive of my writing ambitions as they were when I was in elementary school, hitting away at keys on my new typewriter.

Mine are not the only Arab parents who support their children’s artistic talents. New York-based songwriter and composer Dave Hall, who is of Lebanese descent, said, "My folks always told us ‘Do what you love, that is more important than money.’ So, when I showed musical talent, they encouraged it."

But Hall adds, "I was very fortunate in that." Because Toufiluk’s joke rings true overall – the experience of most children of Arab immigrants is that your parents will frown upon a career in the arts.

Designing Life

Most people are more familiar with stories like that of Dina el-Aziz, an Egyptian-British costume designer who has worked on numerous film and theatre productions in New York, where she’s based, and elsewhere across the US.

"I was very much unsupported," she says frankly. "As a teen, I was bullied by my dad to study medicine but I half-assed my biology and chemistry exams and failed even though I was an A-student in science."

Later, when an attempt to study business made her "miserable", her mother suggested that she double-major in art. Soon, Aziz was designing plays for the college’s theatre department, but "as I continued on, everyone encouraged me to work in a bank or thought I would go into teaching. Literally no one took me seriously till I got into New York University."

Her mother would eventually become a key player and supporter.

Some artists, such as cartoonist and author of The Hookah Girl and A Voyage to Panjikant, Marguerite Dabaie, experienced more extreme reactions from their families.

Dabaie’s father, she recalls, was “very discouraging” of her aspirations to become an artist, and she felt unable to convince him otherwise.

"Since art became a survival mechanism for me," she explains, "I ultimately needed to disconnect myself from my own family to feel like I had the freedom to make it - which I understand is an extreme choice that continues to alter my life."

Chicago-based novelist Sahar Mustafah explains that she entered the teaching profession because she never thought a career in writing was a "realistic possibility".

However, after establishing herself as a teacher, she announced her aspirations to be a writer. “I remember family, and even strangers automatically assuming I was producing journalistic or academic pieces on Palestine. And they were quite effusive about my devotion to showing the world qadiyat falasteen" [the Palestinian cause]. Embarrassed, I couldn't even think of the Arabic word for 'fiction' to clarify my creative endeavours.”

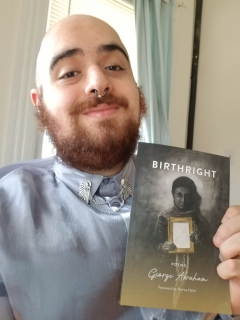

Award-winning poet George Abraham left a STEM PhD at Harvard University to devote their time to a career in writing.

“Although my parents were ultimately supportive, there were a lot of whispers from less close family members saying things like: 'He's gonna be a poor poet now?' or 'Why did you even let him go to school if he was just going to be a writer?'"

American dreams

Many creatives, such as Abraham, who won the Arab American Book Award for their debut poetry collection Birthright, expressed the idea that entering the arts is not “new” for Arabs.

"I'm interested in the ways that immigration and ‘American dream’ narratives have seeped into our family in America, especially given that Palestinian society has, historically, loudly celebrated poetry," Abraham says.

Mustafah, author of the bestselling The Beauty of Your Face, adds: "Art is the most poignant, disarming way of engaging others in our history and culture, and celebrating our humanity."

Award-winning actress Maysoon Zayid, who appears on General Hospital and is the author of Find Another Dream, says: "We are the original storytellers. 1,001 Arabian Nights. We are good at this. That is why it's important our stories are heard and our stories are made."

Zayid herself was planning to become a lawyer when she took a stand-up comedy class. "I was literally studying for the LSATs [Law School administration Tetsts]," she says, "but my comedy got super successful quickly."

Her parents supported her because they saw that it was a lucrative field, but also because it brought her positive attention as a Muslim-American woman, especially in the years after 9/11.

Zayid, who went on to found (with Dean Obeidallah) the popular New York Arab American Comedy Festival, says: "They were very proud of how I represented both my faith and my Palestinian heritage in my work."

Dylan Ramsey’s father took 15 years to “come around” to the fact that his son was making a career in acting.

"I had to make a movie, Extinction, about the last Muslim on Earth, for him to finally support me," Ramsey says with a laugh.

However, when he left Toronto for Los Angeles, Ramsey, like many actors of Arab descent, found Hollywood more willing to cast him in stereotypical roles.

It’s a frustrating experience, one I heard from many other actors – changing Hollywood representation has to be done from the inside, but the work is tedious and progress is measured in small steps.

"The funny thing is," Ramsey says about Extinction, which stars Sally Kirkland and Matthew St Patrick and is on Amazon Prime: "I had to write and produce something to play a good guy."

Increasing representation

Just to be clear, I am not criticising the baba on your shoulder. He has endured difficulties you never will – the anxiety and trauma of immigration is endless, and his intentions for you are good.

However, he also shakes his head in disgust every time an Arab is portrayed in a racist way on a TV show or in a magazine. How can those things ever change if Arabs are not the creators of our own narratives, rather than passive viewers of Homeland and Aladdin?

Neither a renowned heart surgeon nor a widely sought steely lawyer will convince a TV producer to scratch the role of "Terrorist #4" in his new script.

There is reason to hope that things are improving, as more young Arabs launch careers in the arts. Ramsey is a member of the Screen Actors Guild - American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) and sits on the union's newly created Middle Eastern North African diversity committee, which is dedicated to raising awareness about the different Arab cultures for proper representation.

Ramsey also cites other sources available to both actors and producers, such as Muslim List, an initiative by The Black List; the Muslim Public Affairs Council Hollywood Bureau; and Pillars Fund, which focuses on screenwriters who are practitioners or followers of Islam.

"Arab representation has blown up in the last two decades. Our community has a lot of power in Hollywood," says Zayid, citing stars like Ramy Youssef, Sam Esmail, Hiam Abbas, Omar Metwally, and Ryan J Haddad. She adds, wryly: “And we always have Shakira.”

Zayid, one of the most in-demand speakers on Arab-American issues and disability advocacy, says about her family: "I do whole-heartedly believe they’d still rather I became a lawyer and eventually a Supreme Court justice, but comedy will do."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.