The oldest monument on the planet: Now Gobeklitepe gets ready to welcome millions

Sanliurfa, Turkey - Thanks to tourism, it could soon be an attraction like Petra in Jordan or the Pyramids of Egypt, adding this hill in south-east Turkey to the list of ancient wonders of the world visited by millions.

Yet the ancient megalithic site in Sanliurfa makes both of these marvels of architecture look like modern constructions.

The hunter-gatherers who founded this 11,000-year-old sacred site chose their location well. Gobeklitepe, the “Potbelly Hill,” lies 15 kilometres outside Urfa’s city centre atop a strategic hill commanding the Harran plain that faces Syria to the south.

It spreads across nine hectares of fertile land in what was once known as Mesopotamia, where for centuries locals grew wheat and cotton.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

It was a local farmer who discovered the site that would, a few years later, upturn the world’s understanding of human pre-history. Mahmut Yildiz said he was quite surprised when he found the first stones as he was ploughing the field on “an ordinary day” in 1984.

“I knew I had come across something sacred,” he said of the day when he, along with his brother, found the stones. They took them to Sanliurfa’s city museum, with little idea of how ground-breaking their findings would be in relation to humankind’s backstory.

'I knew I had come across something sacred'

- Mahmut Yildiz

At first, the museum did not attribute the stones with much importance. Then German archaeologist Dr Klaus Schmidt, who was working on a nearby archaeological site, insisted on meeting the man who found the stones.

He and his colleague Professor Harald Hauptmann recognised the patterns carved onto the stones right away because of their work at the nearby Neolithic settlement of Nevali Cori.

“Then the Germans came,” Yildiz, now the site’s guard, said in a humble tone, adding that he is “very proud to find something so valuable for the entire world”.

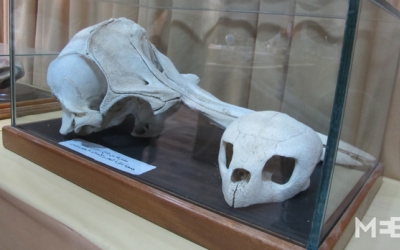

The German Archeological Institute (GAI) and the Sanliurfa Museum began excavations in the mid-1990s, revealing a vast site of stunningly carved figures, some weighing up to 60 tonnes and standing five metres tall.

Pre-history? It needs rewriting

The discovery was a dramatic shock to the academic world, with its well-established chronology and largely settled understanding about the emergence of civilisation. Through Schmidt and his team’s dedication to demystifying the enigma surrounding Gobeklitepe, for the first time, it was set in stone that hunter-gatherers did more than just hunt and gather.

Prior to this discovery, it was assumed that agriculture and larger scale settlement came first - then monumental architecture. Gobeklitepe reversed this order, raising questions as to whether agriculture, which began in the same part of modern-day Turkey, may have been a by-product of the need to feed the large numbers of people gathering at the sacred site.

While thousands of bone fragments of wild animals slaughtered at the site provide evidence that its builders were hunters, within 1,000 years of Gobeklitepe's construction, settlers had corralled sheep, cattle and pigs, explained Schmidt. Then, at a prehistoric village only 30 kilometres from the site, geneticists found evidence of the world's oldest domesticated strains of wheat. They came, they built - and then they farmed.

Yildiz’s discovery could keep archaeologists busy for at least another century, according to Muslum Coban, head of the Sanliurfa Professional Tourist Guides’ Association.

'Wherever you step, there’s something to dig for'

- Muslum Coban

“Wherever you step on, there’s something to dig for. When you enter a dark room and your hand touches things but you are not really sure what they are… That’s what Gobeklitepe is for the history of humankind,” Coban, said, hinting that this is only the beginning of a massive set of discoveries to come.

It’s unclear how many more of these monumental structures lie hidden at the site, Coban said, “and that’s one reason why there’s so much mystery around this space”.

The goal: More visitors

In 2019, the region is expecting more tourists from around the world than ever before. Covered by a 4,000-square-metre steel protective roof that cost 6.6 million euros to build, Gobeklitepe is a rising star getting ready to show visitors its invaluable message from over 11,000 years ago.

According to Aydin Aslan, provincial director for culture and tourism, Gobeklitepe will be given special emphasis at expos where Turkey is featured.

Before the Syrian War began in 2011, visitors from the US and Europe were increasingly coming to the site. Then in the aftermath of the siege of Kobane in northern Syria in 2014, the number of visitors slowed down, Coban said.

Yet according to Coban, in 2018, the numbers crept up again, as some 4,000,000 tourists - most of them travelling from Turkey’s big cities such as Istanbul, Ankara and Eskisehir – visited.

Predating the Great Pyramid by 7,000 years and Stonehenge by at least 6,000, last year Gobeklitepe became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In December, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared 2019 “Gobeklitepe Year,” with visitor numbers expected to skyrocket. When 2018 was declared “The Year of Troy,” tourism in the north-western Canakkale province increased by 60 percent, Erdogan said during his declaration.

“I believe that we will see a much higher performance in Sanliurfa. This ancient settlement proves the importance of Anatolia in the history of humanity and it will certainly attract worldwide attention," Erdogan said.

Hunting for the ‘black box’

No excavation site in the world has so profoundly reshaped the tale of how our ancestors transitioned from hunter-gatherers to civilised settlers. Still deemed a mysterious “black box” in terms of the human story, this pre-pottery Neolithic site stands as the oldest monumental architecture discovered on the planet.

“[Gobeklitepe] was not built by great civilisations, but by hunter-gatherers who were still to a certain extent mobile,” said Dr Lee Clare from GAI, who is also coordinator of the on-site excavation team.

“It was totally unexpected that late hunter-gatherers at this time could build monumental, megalithic structures like this,” he said. “That’s what completely blew us away and threw everything out the window,” he added.

'It was unexpected that late hunter-gatherers at this time could build monumental, megalithic structures like this'

- Dr Lee Clare

The Bronze Age was yet to arrive, so these mobile groups did not have access to metal and they had not invented the wheel or the written word, Dr Clare explained, adding “we don’t know a great deal about who these people are, or who came before them.

“Oral tradition and oral narratives were for the first time carved into massive limestones - a task that requires high skills,” the archaeologist said, making the point that these hunter-gatherers were producing a multi-functional narrative of their own to possibly keep the group together in the face of increasing social inequality.

According to the German archaeologist, these figures also indicate that the builders had special ties to their ancestors and to animals, such as vultures, scorpions, leopards, wild boars and lizards.

“Perhaps there were elements of something similar to shamanism, so we can also talk about animism,” Dr Clare said of the humans who built Gobeklitepe.

Understood to represent the human form, the massive carved T-shaped pillars have become a signature of the site, standing up to 5.5 metres high, and each weighing tens of tons. And it is believed that the stones were quarried 300 metres or so from the site.

“On the stones, there’s architecture, geometry. They tell a story. They knew who they were, and they knew who they were depicting. We can only make educated guesses about what these figures depict, but there’s a narrative,” the German archaeologist said, noting the figures carved on pillars in Gobeklitepe are not readable like that of the hieroglyphs in Egypt as there is no identified alphabet here.

Though the site is widely marketed as the world’s oldest temple, Clare qualifies this idea. “It’s a big meeting place,” he said. “It is a social hub where hunter-gatherers could express social traditions and beliefs.”

He explained that this particular site could only be truly understood when looked at in the context of a network of nearby excavation sites, such as Nevali Cori and Harbetsuvan Tepesi that are also pre-Neolithic sites in Sanliurfa.

“The earliest phases of Gobeklitepe are older than Nevali Cori,” Dr Clare said, referring to the other significant settlement on the middle Euphrates. He confirmed the two groups living within the “Fertile Crescent” borders would have known one another.

“[Gobeklitepe’s] architecture and artefacts are very similar also to those in Northern Syria. The [groups] would have contacts over a large area in Mesopotamia. They share symbols and similar values, but have regional differences,” the archaeologist added.

More visitors means more risks

Dr Clare underlined that older centres of art have been identified, such as the French and Spanish cave paintings that are thought to be some 15,000 to 17,000 years old, but Gobeklitepe is the most exciting because it’s also home to the oldest man-made megalithic structures.

Although he welcomed the decision to encourage tourism and make 2019 the year of Gopeklitepe, Dr Clare said the campaign brings certain risks. For this reason, he said the archaeological team are actively working on protection mechanisms that aim to preserve the site as more visitors attend.

Since the site can only be reached through a shuttle bus after a certain point and there are security cameras, according to Dr Clare they are already pretty much in control of how many people can be allowed near the excavations at a given time.

“We are very aware of the challenges and we will not let the value of the site get run over by a boost in tourist numbers,” Dr Clare said. A site that is, so far, unique, Gobeklitepe is a universal value we should protect.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.