Who is Mahmoud Abbas, Palestinian Authority president - and why does he matter?

Mahmoud Abbas, a long-time politician and architect of diplomatic ties with Israel, has been the president of the Palestinian Authority (PA) for nearly two decades since the death of former leader Yasser Arafat.

Before dominating Palestinian politics, Abbas was central to signing the 1993 Oslo Accords that established formal relations between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).

An ardent opponent of armed struggle, the PA under his leadership sought Palestinian independence and international recognition through diplomacy. His greatest achievement has been securing non-member observer status for Palestine at the United Nations.

But his strategy has failed to stop land appropriation and the expansion of Israeli settlements, which run counter to international law, in the occupied West Bank. Talks with Israel have also been frozen under his rule for years, gradually diminishing the prospect of a two-state solution.

Internally, his critics say Abbas enforced authoritarian policies that eroded democratic institutions, dismissed rivals and consolidated powers in his hands. He also oversaw a split in the governance of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 2007, following violent confrontations with rival group Hamas, the biggest Palestinian armed group opposed to recognising Israel.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Now 88 and based in Ramallah, Abbas has yet to sketch out a clear and democratic succession process, leaving the future of the PA in the balance.

When did Abbas join Fatah?

Mahmoud Rida Abbas, also known as Abu Mazen, was born in November 1935 in Safed, then part of Palestine. In 1948, Zionist militias forced his family to flee to Syria during the ethnic cleansing of Palestine that led to the establishment of the state of Israel, an event known to Palestinians as the Nakba (“catastrophe”).

Abbas graduated with a law degree in 1958 from Damascus University and was awarded a PhD in 1982 from the Oriental College in Moscow for his thesis connecting the Nazis to leaders of the Zionist movement. His thesis, which was later published in a book, led to accusations of antisemitism, which he denies.

In 1954, Abbas was part of a clandestine group that provided professional military training for Palestinians. He enrolled in a military college in Homs but was expelled a month later when the administration told him and his colleagues that they were unfit.

Three years later he moved to Doha and worked in the education ministry, where he met Palestinian activists, including Abu Youssef al-Najjar, one of the Fatah movement co-founders. During this period, Abbas also met Arafat, who at the time lived in Kuwait.

In 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) had become an umbrella organisation for Palestinian political groups: five years later, it was led by Arafat and, by extension, Fatah.

What role did Abbas play in the PLO?

Abbas relocated to Amman, Jordan, in 1964, from where he participated in the mobilisation of Fatah for the next decade.

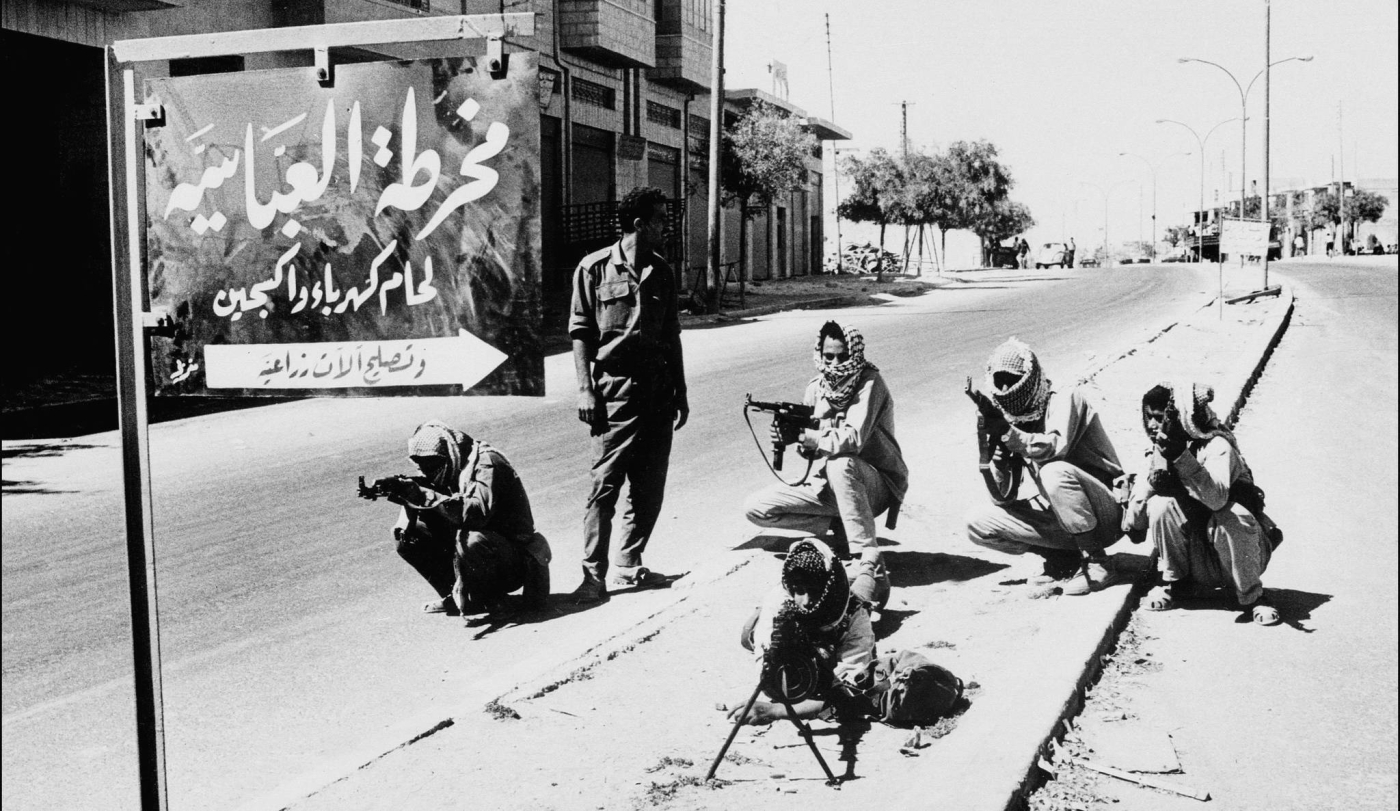

Fatah’s initial purpose was to liberate historic Palestine using armed struggle against Israel. It was the first Palestinian group to attack Israel, although there is no evidence that Abbas was involved in any military actions throughout his life.

After the Black September conflict with the Jordanian state, the PLO was expelled from Amman. Most of the group relocated to Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon - but Abbas returned to Damascus.

In the 1970s, Abbas was a key figure in a faction that emerged within Fatah which favoured political dialogue over armed struggle against Israel. He was instrumental in establishing contact with leftist Jewish and Israeli groups at the time, and part of the first secret “peace talks” between the PLO and retired Israeli General Mattityahu Peled.

In 1980, Abbas became the head of the PLO’s department for national and international relations.

Why did Abbas want talks with Israel?

In 1982, Abbas relocated to Tunisia with the PLO after the organisation was driven from Lebanon amid the invasion by Israel that summer.

Fatah dropped its categorical opposition to normalisation with Israel by 1987 and the First Intifada, instead engaging in negotiations for a political solution. This shift towards diplomacy led to the 1993 and 1995 Oslo Accords between the PLO and Israel, overseen by Abbas, and eventually the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA).

Abbas was central to these deals, and accompanied Arafat to the White House on 13 September 1993, where he signed the Oslo Accords on behalf of the PLO.

In 1994, Abbas wrote from Tunisia: “The mindset of the revolution is different from that of the state and it is the responsibility of our people to build something out of nothing. This is the challenge we are faced with. Having contributed to achievements that placed our people at the forefront of history, I remain deeply concerned that we could get swept away by history, lose control and suffer an unrecoverable setback.”

The PA was intended to serve as a five-year interim self-governing body, eventually establishing a state in the Palestinian territories that Israel occupied in 1967, including East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

But the agreement faltered within years and a Palestinian state was never established. Newly formed groups like Hamas and the Islamic Jihad rejected the deal, seeing it as a concession of 78 percent of historic Palestine to Israel.

The right-wing opposition in Israel also attacked the agreement. It culminated in the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin at a rally in Tel Aviv in November 1995.

More broadly, during the past three decades, Israel has expanded its settlements, which are illegal under international law. It also maintained its military occupation of Palestinian territories, with the PA now exerting only limited control over small parts of the West Bank.

Why did Abbas fall out with Arafat?

Abbas was promoted through the ranks of the PA and became the second most senior figure after the Israeli assassination of key Fatah commanders, including top Arafat aide Khalil al-Wazir, and following the Oslo Accords.

Despite this, his relationship with Arafat was not always smooth. When the PLO entered the West Bank in 1994 after Oslo, Abbas did not do so for more than a year. In a 2017 interview, Nabil Shaath, a prominent Fatah figure, said Abbas disagreed with Arafat on how he established the PA and may have wanted greater responsibilities.

Their relationship worsened during the early 2000s. Arafat backed the Second Intifada after negotiations with Israel on “final status issues” faltered. But Abbas rejected the Second Intifada, later calling it the “one of our worst mistakes”.

Subsequent Israeli attacks in the West Bank and Gaza, including at the PA headquarters in Ramallah, fatally undermined Arafat.

In 2003, the US-led “peace initiative” tried to return to the pre-Intifada status quo - but Israel and the US refused to negotiate with Arafat. Instead Washington pressured him into appointing a prime minister in February 2003: Mahmoud Abbas.

Abbas led the US-sponsored talks with Israel’s then-prime minister, Ariel Sharon, but was criticised by Arafat, the Palestinian parliament and the public for his willingness to concede on key issues such as Palestinian prisoners detained by Israel, and his push to disarm Palestinian groups.

In September 2003, as his power struggle with Arafat worsened, Abbas resigned both as prime minister and from the Fatah Central Committee.

What does Abbas think of Hamas?

After Arafat died in November 2004, Abbas was elected by Fatah to lead the PLO. In January 2005, he claimed victory in the PA’s second - and so far, last - presidential elections, taking 62.5 percent of the vote. But in January 2006, whatever consensus Abbas built around himself and Fatah crumbled.

The group lost its hold on the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) - which acts as a parliament - to Hamas: many attributed Fatah’s defeat to its renunciation of armed struggle under Abbas.

The PLC elections were seen as free and fair by international observers, but the results were condemned by western countries for giving rise to Hamas, which is designated as a terrorist group in the US, UK and other countries.

The rival parties formed a unity government but it descended into armed conflict in June 2007 after months of political tension. Hamas accused Fatah of plotting to overthrow its government as part of a US-led plan. Street battles in Gaza left over 100 people dead and drove Fatah officials out of the strip.

The split left the PA presidency, led by Fatah, in the West Bank. Hamas claimed control over the legislature and Gaza. But the PLC practically ceased to function. Its mandate to make laws was soon transferred to Abbas as the head of the PA.

The division between Hamas and Fatah has persisted since, despite many attempts at reconciliation over the years.

Abbas’ actions since have been criticised, including how the power of the PA has coalesced in the presidency at the expense of the executive and legislative branches. The presidency, for example, has exploited the absence of the PLC to enact dozens of laws.

In 2018, Abbas was again criticised for imposing punitive measures against Gaza to pressure Hamas during reconciliation talks, cutting salaries of PA employees and blocking fuel payments, thereby reducing the enclave’s already limited hours of electricity.

What do Palestinians think of Abbas?

Many Palestinians are critical of Abbas, not least for his suppression of individual freedoms in the West Bank. Hundreds of dissidents, including students, have been arrested by PA security forces. Some say they were tortured: many were released, then detained by Israeli forces shortly afterwards.

The Electronic Crimes Law passed in 2017 has curtailed freedom of expression. There have been sporadic crackdowns on media critical of the Palestinian authorities. Protest movements in the West Bank - including school teachers, opponents of punitive measures against Gaza, or critics of security coordination with Israel - have been violently suppressed by PA forces.

Perhaps most controversial has been how the PA, under Abbas, has coordinated and shared intelligence with Israel about Palestinians suspected of planning operations against the occupation.

Abbas stated publicly several times that security coordination with Israel is “sacred”: some have suggested that the PA’s survival is only due to this policy.

Over the years, Abbas made repeated threats to end the policy but with little follow through.

Within Fatah, Abbas has presided over splits within the group that eroded its unity, excluding two key leaders from the movement, Mohammed Dahlan and Nasser al-Qudwa, amid disputes.

What has Abbas said about the Palestinian right to return?

During the Nakba, Abbas’ family were forced to flee their homeland to neighbouring countries with hundreds of thousands others.

For the millions of Palestinian refugees around the world, whose families were displaced in 1948 like Abbas’ family, the right of return to their homeland is sacred (some still possess the keys to the homes that they or their ancestors were driven from).

But in 2012 Abbas said that he did not long to return to Safed, from where his family were driven by Zionist militia. “I want to see Safed, I have the right to see it, but not to live in it,” he said. “Palestine in my view is on the 1967 borders, with its capital East Jerusalem. This is the situation now and forever.”

The statement caused uproar among Palestinians: many feared that his comments were a possible prelude to renunciation on their behalf. It only added to the sense for some Palestinains that Abbas does not always have their best interests at heart.

How is Abbas seen internationally?

Abbas has proved more popular on the international stage, including his push for the recognition of Palestine.

In November 2012, the UN General Assembly voted to recognise Palestine, based on its 1967 borders, as a non-member state with observer status.

Ahead of the vote, Abbas told delegates: "The General Assembly is called upon today to issue a birth certificate of the reality of the state of Palestine.” He later said that it was the body's "last chance to save the two-state solution”.

The move boosted Palestine’s standing, enabling it to join key international treaties and institutions, including the International Criminal Court (ICC).

In 2018, the PA submitted a referral to the ICC to investigate “Israeli crimes” in the occupied Palestinian territories for the first time. The investigation is still ongoing.

But even before the 2023-24 Israeli war on Gaza, Abbas' efforts to secure further international backing were ringing hollow.

Israel, with the backing of the US and especially during the presidency of Donald Trump, has moved ever closer to annexation and expansion of settlements in the West Bank.

Many Palestinians and international observers conclude that the two-state solution is unachievable, along with justice and equality for Palestinians.

Who will replace Abbas?

A heavy smoker for most of his life, Abbas’ health has led analysts to long speculate as to who might replace him. Many have criticised his continued hold over the presidency, despite his term expiring in 2009. Abbas has never publicly designated a successor.

Many analysts believe the most likely candidate to lead Fatah is Hussein al-Sheikh, who Abbas appointed as the secretary general of the PLO executive committee in 2022, the second-highest position inside the organisation. Another contender is Majed Faraj, the head of the PA's General Intelligence Service and a close aide of Abbas.

But neither man enjoys popular support and is unlikely to win in any potential PA presidential elections.

The appointment of one of them via presidential decree would likely be seen as illegitimate and be met with public opposition.

What will be the legacy of Abbas?

Palestinian support for the two-state solution is much weaker today than when Abbas took office. He will leave behind a politically divided people, a weakened Fatah movement, and a much more entrenched Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories.

Two decades after Abbas was elected president, the prospect of a negotiated settlement with the Israelis has never seemed so distant. Instead, Abbas will be known as the Palestinian president who secured a UN non-member observer state for Palestine, but failed to achieve full recognition.

He will also be remembered as the president who clamped down on armed resistance against Israel, considered the security coordination with Israel as “sacred”, and oversaw the authoritarian shift within the PA.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.