Behind the doors of Beirut's indie music revolution

BEIRUT - It is Friday night in Beirut. While crowds are gathered in the city's most popular bars and restaurants, they casually share drinks on the sidewalk.

Others walk into a bar and instead of ordering something, they disappear behind a set of doors. Similar to Alice going through the Looking Glass, Beirutees pass through Memory Lane – for that’s the name of the bar – and step into a different world.

Behind the third door lies Beirut Open Space (BOS) – a brand new concert venue for alternative local bands. The simple and effective venue can host up to 250 guests, with its stage, low lights, high tables and a dance floor.

“We want to strengthen the music scene. All the elements exist but they were spread out. With this place, artists can meet, perform, support each other and even collaborate,” said Elias Maroun, co-owner of BOS.

“The challenge is to educate the crowd to appreciate small music venues, they are not used to it,” added Ramzi Khalaf, co-owner of BOS.

The challenge is to educate the crowd to appreciate small music venues, they are not used to it

- Ramzi Khalaf, co-owner of Beirut Open Space

The crowd fell silent the second the concert started. Everyone stared at Maya Aghniadis, also known as Flugen, a young girl with a red spot-light directed on her. All by herself, she is an entire band – singing, playing keyboard, acoustic guitar and even the flute.

Her music mixes oriental tunes with Latino influences, creating a slow and captivating rhythm.

After the first song, a man with salt and pepper hair immediately climbed up onto the stage. He whispered to the artist, moved a few cables around and fixed a minor sound issue. Paying close attention to every detail but keeping a low profile, this is music producer Fadi Tabbal, who has been described as the godfather of alternative music in Lebanon.

The Arabic music scene

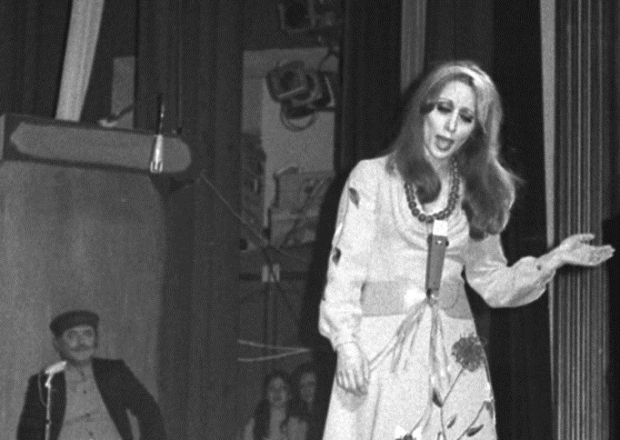

Flugen, like many other artists, is a not really recognised in the Arabic music scene yet. Since the 1950s, Middle Eastern radio waves have been saturated with the voices of Oum Koulthoum, Fairouz, Warda and other Arab divas.

As satellite television and music video clips peaked in the 1990s, pop-stars took over with the help of ambitious producers. Icons such as Haifa Wehbe, Elissa or Nancy Ajram became the face of contemporary Arab music. Arab pop is associated with catchy love songs, plastic surgery and opulence.

But during that time, some kids in Lebanon were listening to something else.

Fadi Tabbal was born in 1982, right in the middle of Lebanon’s civil war (1975 – 1990) and raised to the sound of American folk. His first musical shock came in 1997 when British rock band Radiohead released their album OK Computer.

The solo guitar sounded like a computer

-founder of Tunefork Recording Studios and co-owner of BOS

From then on, Tabbal developed a passion for sound arrangements. While studying mechanical engineering in Beirut, he took up a part time job at a record store where he deepened his knowledge about alternative music and started a progressive rock band called April Ash.

Being a Canadian passport holder as his parents lived there for a while when he was younger, he then took the opportunity to specialise in sound engineering in Montréal.

Coming back home in 2006, he had one ambition: open a music studio where Lebanese and Arab alternative music would thrive.

Tunefork recording studios

Tunefork Recording Studio is located on the seventh floor of a tall, grey and dull-looking building in the northern outskirts of Beirut. From a tiny balcony near the entrance, there is a view of a giant parking lot.

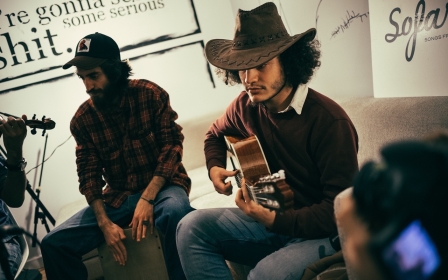

Rehearsing at the studio is Selim Naffah, a 25-year-old musician who released his first album Sex Tapes under the band name Alko B in early 2017.

“Today, anyone can record an album at home with a computer, but Fadi’s studio is a space where we as artists feel comfortable,” he said as he practiced one of his songs on his guitar.

“All our musical education comes from Fadi. We are lucky to be under his wing. What he teaches us is to think of music in three dimensions. There is you, your instrument and the space around you. We watch him, the way he listens to the sound, the way he looks for details and texture that will stimulate emotions,” he added.

Tabbal sits behind a glass window with his glasses on. Even in his studio, he keeps a low profile.

“Not many people listen to this kind of music here – maybe 1500 people I would say, especially if you are singing in English; so it’s not a lucrative business but that’s what I like,” he said.

These kinds of musicians usually sing in English, although some like Mashrou’Leila, Yasmine Hamdan or Adonis were very successful with Arabic lyrics. “When I produce a band, I don’t charge for production, only for studio fees, so I don’t really make money. It’s barely enough to cover the costs of the studio. In some cases the band can’t even afford the real costs of recording an album, but I’ve never stopped a project in the middle.”

According to Tabbal, the fees for the studio barely cover rent, utility bills and the equipment. Once their songs are released or if they become popular, he does not take a percentage of the band’s earnings.

As he cannot rely solely on his studio to make a living, Tabbal also works as a musician, composer, university professor in aesthetics of sound, sound mixing, editing, and as a producer.

Tabbal also has a solo act and is currently a member of four active bands, where he plays the guitar and helps compose. These bands include pop group Safar, indie rockers Interbellum, electronic post-rock band The Bunny Tylers and electronic duo Stress/ Distress.

Additionally, Tabbal composes music for movies, documentaries and commercials.

I don’t want to be labelled as the guy who records Western sounding music only because it makes me sound pretentious

– Fadi Tabbal, founder of Tunefork Recording Studios and co-owner of BOS

“For some reason, at one point I was doing a lot of music for diaper adds,” he recalls laughing.

So far, Tabbal has produced approximately 25 artists and 50 albums. A few years ago, some of his proteges such as Mississippi blues band, the Wanton Bishops or electro rockers Who Killed Bruce Lee made it big when they embarked on concert tours around the world. But Tabbal does not want their success to overshadow the rest of his work.

“What they did is great, but I don’t want to be labelled as the guy who records Western sounding music only because it makes me sound pretentious - which I’m not. I also work with a lot of other artists, other genres like classic oriental, experimental improvisation or free jazz,” Tabbal said.

A work in progress

Because they do not have access to traditional distribution channels such as radio or TV stations, which usually focus exclusively on imported music or Arab Pop, alternative artists have to rely on other networks to make themselves known.

Many of them use YouTube, Soundcloud and social media for self-promotion, but in the last few years a whole eco-system has started building up to push artists forward.

Co-founder Junior Daou was friends with many Lebanese musicians when one summer he decided to start organising concerts. Using a 3,500 square-metre piece of land owned by his family in the northern seaside town of Batroun, he invited the musicians to play there.

“I obviously knew nothing about concert organisation, but there was nothing like this at the time. So I read a lot, watched documentaries, asked for help here and there and gave it a try,” Daou said. At the time, Daou was expecting 500 people, but 1700 showed up.

“The plan was to do this as a one shot, but it got out of hand,” he recalls.

The festival became an institution and every September music lovers gather there for an afternoon of the latest music.

This year, Tabbal was behind the scenes working as the festival's sound engineer and playing on stage with the Lebanese band Bunny Tylers.

Just like Tunefork Studios, Wickerpark does not earn much money. Tickets sell for about $30 each and there are a few sponsors such as Dewar's Whisky and Beirut Beer, but it is not enough to make it profitable.

For now, many Lebanese musicians keep a steady side job, but as the music scene progresses, they may attract more investors.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.