Being Erdogan: Actor says biopic of president is not AKP propaganda

ISTANBUL, Turkey - Turkish actor Reha Beyoglu takes a moment to wipe the sweat off his forehead before yet another fan insists on having a selfie taken with him. The star has quite a reputation to uphold, so there is little else he can do but keep smiling.

In his latest film that premiered on President Recep Tayyip Erdogan 63rd birthday on 26 February, Beyoglu is playing the role of Erdogan in Reis - "The Chief."

Yet for critics the timing of the movie is linked to another important date: the 16 April when Turkey will be holding a referendum on constitutional amendments, that would give the president sweeping executive powers.

'I truly love Tayyip Erdogan. As an actor, it is an indescribable joy to play the part of your president'

- Reha Beyoglu, Turkish actor

Beyoglu is quick to dismiss any suggestion that the film is linked to the referendum. “There is no way that this [is a] propaganda movie or anything like that. It’s a biography. And when you are showing the life of the most important person in Turkey, I can assure you that the scenario writers cannot just use their fantasy. We are showing reality.”

That said, the Turkish actor clearly admires his character.

"I truly love Tayyip Erdogan. As an actor, it is an indescribable joy to play the part of your president. But it’s also a responsibility because I realise that I’m now associated with him. I therefore do my best to make sure that any of my own mistakes are not linked to our president."

Reis tells the story of Erdogan’s life, starting from his childhood until he became the mayor of Istanbul and ending around his imprisonment in 1999. Directed by Hudaverdi Yavuz, Yavuz insists that the government has not influenced his work and funding was obtained by Dutch-Turkish businessman Temel Kankiran.

Erdogan's beginnings

While his friends are rummaging around or getting into fights, a young Erdogan calls them to order: "Let’s go to the mosque guys," he says in the movie.

This sense of duty quickly leads to a career in politics, as the film traces Erdogan’s rapid rise in the municipality and shows how as mayor of Istanbul he drastically improved the living conditions of ordinary Turks.

Religion vs state

Aside from focusing on Erdogan, the film emphasises a clear-cut distinction between an oppressed religious population on the one hand and an authoritarian secular state on the other.

The military has long described itself as the guardian of secular Turkey, established by the country’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. Between 1960 and 1980, several military coups took place in Turkey. Then in 1997, the army led a campaign that forced Turkey’s first Islamic-led government to resign.

In one of the first scenes, we see Erdogan’s father weeping because of the death of Adnan Menderes, the Turkish prime minister who during the 1950s gained great popularity among pious Turks, according to the film. One year after the coup in 1960, Menderes was executed by the secular military.

'The mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers',

- Poem, read by President Erdogan

"A great man has passed away today," Erdogan’s father told his shaken son in the film, "But if you work hard, you will one day become just as great," the character added.

Reis sheds light on the constant battle between religion and state in Turkey. This is clear in a teaser released last year where a soldier hits an elderly imam with a rifle for performing adhan (the Muslim call to prayer) in Arabic. The gathered crowd is taken back by the cruelty they witness, until suddenly a high-pitched boy’s voice travels through the streets. An eight-year-old child continued to recite the adhan, where the imam had left off. The soldier depicted in the film does not dare intervene against the courage displayed.

There was a ban on reciting the Islamic call to prayer in Arabic from 1932 until 1950 in Turkey. At the time, the people had to recite the adhan in the Turkish language only.

Menderes is mentioned again towards the end of the film, when Erdogan himself is condemned to prison for publicly reading an Islamic poem, following the military coup which forced Turkey’s first Islamist prime minister Necmettin Erbakan to stand down in 1997. The poem said:

"The mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers."

It is hard to estimate what scenes like this signify for Erdogan’s supporters, especially in the light of last summer’s failed coup.

However film has done poorly at the box office since its release and many of Turkey’s popular commentators from mainstream newspapers have panned it.

A political message

According to Mesut Bostan, a research assistant at Marmara University specialising in the relation between populism and Turkish cinema, Reis clearly carries a political message.

“But that in itself is nothing new in Turkey. Already from the 1960s, Turkish cinema had become especially politicised,” Bostan said.

'Not so long ago, female actors wearing the veil would often play the role of suspicious Islamists'

- Mesut Bostan, research assistant at Marmara University

What changed was the content of these films.

"Not so long ago, female actors wearing the veil would often play the role of suspicious Islamists," he explained. "Nowadays, a film like Reis is equally exaggerating and simplifying reality, but especially when it comes to the Kemalist regime. The latter is presented as unchanging and authoritarian, whereas in reality relations between state and citizens have been more fluid."

Bostan said that some of facts in the movie were questionable. He referred to the scene in which the soldier struck the imam for performing adhan in Arabic, saying that it was “very anachronistic”, since the ban was lifted in 1950, while the the movie states that the incident occurred in the 1960s.

The Ottoman era is another favourite in the cinematic revision of Turkish history. For example, the 2012 action movie Fetih 1453 (Conquest 1453) presents Turkey's victory as a clear-cut triumph of noble Muslims over corrupt Christian Byzantines. It was an enormous hit in Turkey.

Television has also had its share of successful shows such as Muhtesem Yuzyıl (Magnificent Century), on Suleiman the Magnificent, one of Ottoman Turkey’s most famous sultans. According to Turkey’s state Anadolu Agency, it has been watched over 250 million times in 70 different countries.The Ottoman era

Cinema can carry political power in Turkey, but to portray it as a simple tool of AKP-policy would be naive, according to Bostan.

"These films and series have clearly contributed to an ideological climate that is favourable to the AKP. But without genuine interest from society, they would never have become this popular," he said.

Still, the academic is pessimistic. "Ten years ago the renewed interest in the Ottoman period was part of a democratisation process. The idea was to have an open debate on a period which was long looked down upon by Kemalist historians. The irony is that we now see that, once again, one version of Turkish history is being emphasised over all others, just like the Kemalists did,” he added.

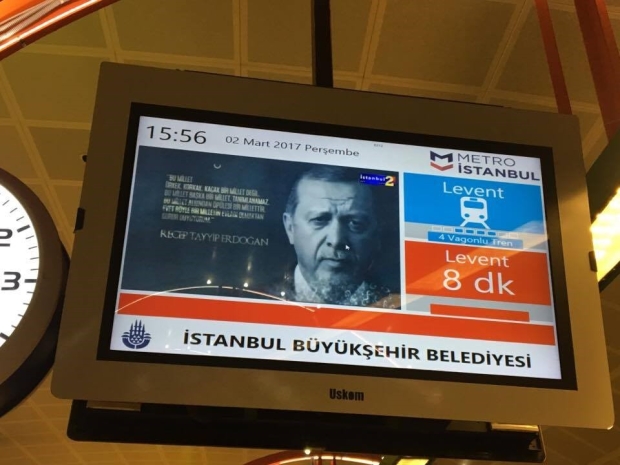

This has consequences for the future. In its latest campaign video, the AKP is citing wisdom from famous late Ottoman Sultans to serve as a voting guide in the upcoming referendum on the presidential system. The clip was first broadcast by Turkish state Television TRT last month and is also visible in public spaces such as the Istanbul metro.

"Life’s not a movie," the voiceover urges, as galloping horses and Ottoman war music thunder in the background.

Images of several famous sultans whiz by the screen, after which a portrayal of Ataturk fades out into one of Erdogan. The key message of this video is one that was learned long ago by Turkish filmmakers: "It is good to take lessons from history, but what really counts, is to create it."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.