BOOK REVIEW: Richard Falk’s Chaos and Counterrevolution - After the Arab Spring

Chaos and Counterrevolution: After the Arab Spring by Richard Falk

Published by Just World Books 2015, Virginia, USA (ISBN:9781935982517, Release date: June 2015)

Richard Falk’s new book delivers much more than the title suggests. Its focus may be the aftermath of the “Arab Spring,” but it could well act as an introduction to the political crosscurrents and armed conflicts that have convulsed the region over at least the last 50 years.

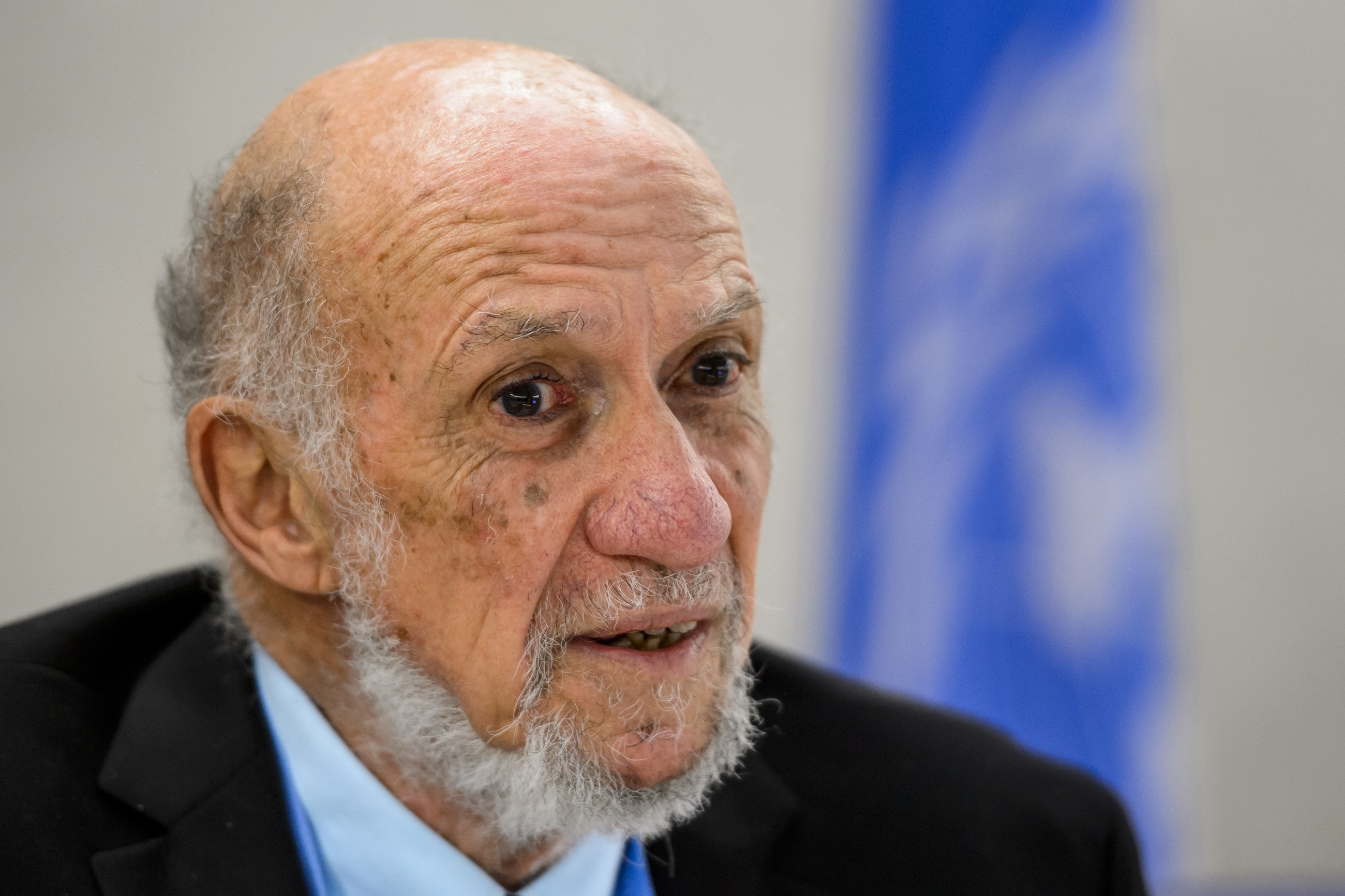

Falk is a professor of international law and from 2008 to 2014 acted as the UN special rapporteur on the Middle East. Not only have his years with the UN and his legal background given him a unique analytical vantage point; he has impeccable credentials as an activist working for a more just world order. These were forged in his decade-long opposition to the Vietnam war, which he sees as sowing the seeds of later military interventionism in the Middle East and elsewhere.

In relation to the Middle East, Falk was an early opponent of his country’s support for the Shah of Iran and he followed closely the unfolding of the root-and-branch Iranian revolution. This he contrasts with the more recent uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia “which were content to rid the country of the hated ruler, but otherwise sought to achieve their democratising and economic goals through the established order associated with the old regime” (page 202). He implies this is one reason for the failure of the “Arab Spring” in Egypt, although he retains some hope for Tunisia, less strategically placed and “politically blessed with the absence of oil” (page 229) - and therefore less vulnerable to outside intervention.

For this book Falk has made a selection of his blog posts from 2011 onwards when the Tunisian revolution kick-started the wave of uprisings across the Arab world. He is best known to many for his detailed and outspoken criticism of Israel policies and of US support for them. There is an irony in the fact that it was Israel’s decision to expel him in 2008 that led him to study in depth other parts of the region, making this book possible. It is really a companion volume to his 2014 book Palestine, the Legitimacy of Hope. The focus here is on other countries of the region with a chapter each being devoted to Egypt, Libya, Syria, Turkey, Iran and Iraq.

The blog format lends a freshness and immediacy to his analysis, and more often than not his misgivings – such as his warnings in relation to NATO intervention in Libya – have proved to be all too well-founded. However, an overview is achieved by his carefully considered introductory chapter and by the separate introductions he provides to each individual chapter. The lucidity of his style guides the reader through the bewildering labyrinth of power struggles and shifting alliances that characterise the Middle East.

A central theme is the way in which the US has repeatedly sought to control the region by propping up repressive and anti-democratic regimes that are compliant with US and Israeli interests, like Saudi Arabia or Sisi’s Egypt, while seeking to bring down any regime showing signs of political independence. Sisi’s regime in particular he sees as serving Israeli and US interests, “restoring stability, marginalising Muslim and democratising forces, and avoiding the emergence of governments much more inclined to support Palestinian aspirations and to challenge neoliberal links with global capitalism” (p240). Quite simply, “Where there is oil and an anti-Western government in power, recourse to the military option follows, or at least an insistence on sanctions that aim to be crippling and regime-changing” (page 204).

Falk demonstrates clearly that the military intervention in both Iraq and Libya had no legal basis. Therefore, “... not only was the Iraq war a disaster from the perspective of American and British foreign policy and the peace and stability of the Middle East region, it was also a severe setback for the authority of international law, the independence of the UN and the quality of world order.”

Although Saudi Arabia is not given a chapter to itself, Falk has a good deal to say about its role in the region and beyond, with its heavily funded export of Wahhabi Islamism, and its efforts both to suppress the Muslim Brotherhood and to turn the military might of Western countries against Iran. In both cases, Falk interprets this as Saudi fear of any anti-monarchical Islamic regime, be it Sunni or Shia, that might offer an alternative to its own harshly fundamentalist brand of Islam. Hence the kingdom has emerged as a strange - or perhaps understandably compatible - bedfellow of the increasingly extremist Zionist regime in Israel.

In relation to the threats against Iran, he says: “No international-law argument or precedent is available to justify attacking a sovereign state because it goes nuclear. After all, Israel became a stealth nuclear-weapons state decades ago without a whimper of opposition from the West, and the same goes for India, Pakistan and even North Korea” (page 224).

A major chapter devoted to Turkey, which he knows well on a political and personal level - his wife is Turkish - throws additional light on the region’s politics. (Falk is much less critical of the ruling AKP party than many western commentators, pointing to Turkey’s impressive economic progress, and the principled stance taken on the Israel/Palestine issue.) With the Islamic State and a nascent Kurdish republic on Turkey’s borders, Erdogan is faced with something of a dilemma. His longstanding hostility to Assad’s regime has been tempered by the need to find a solution to the decades-long conflict with Turkey’s own indigenous Kurdish community.

Unsurprisingly, Falk is not optimistic about the future of the region. He does, however, put forward a partial solution to its conflicts and tensions. He proposes: “... a nuclear-weapons-free zone, coupled with a regional mutual security framework agreement that includes Iran and Israel. If these steps were reinforced by effective geopolitical pressure to accept the Israel-Palestine normalisation procedures set forth in 2002 (known as the Arab Peace Initiative), regional prospects for peace and security would be greatly improved” (page 18).

What he believes will actually prevail is a continuation of America’s addiction to military options: airstrikes, including drones, and the use of local ground forces to avoid American casualties with scant regard for the devastating effects on local populations. His closing sentence is redolent with something approaching despair: “Dispiriting repetition occurs instead of uplifting innovation and the wheels of violence turn with accelerating velocity.”

- Hilary Wise is a writer, an academic and an activist. She also was editor of Palestine News for eight years.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.