Egypt's rock rebel Ramy Essam: 'My cause is humanity and freedom'

VANCOUVER - Ramy Essam has been called a revolutionary, and the voice of Egypt’s lost generation. But the man who turned the chants of thousands of disenfranchised voices in Tahrir Square into anthemic pop protest songs prefers to be called an artist.

"I’m no politician,” says the 30-year-old Essam. “I don’t even like people to call me an activist. I am just an artist singing about the cause.”

'I don’t even like people to call me an activist. I am just an artist singing about the cause'

-Ramy Essam

Essam has already packed a lot into his three decades, his comfortable middle-class life transformed forever by his Tahrir Square fame and later his torture, arrest, interrogation and subsequent offer of refuge in Sweden.

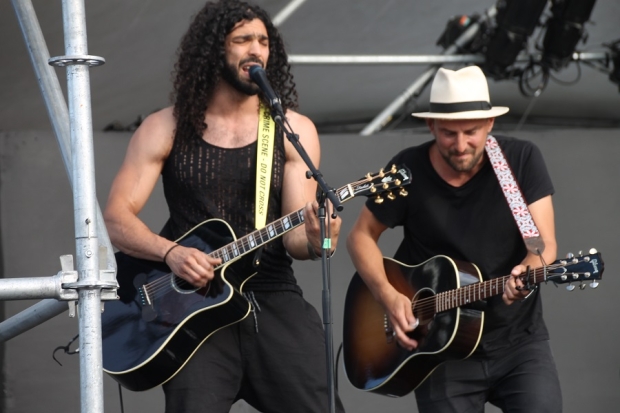

Interviewed at the Vancouver Folk Music Festival in Canada during his current tour in North America, the largely ageing white boomer crowd ate up his blend of Nirvana meets the famous Algerian singer and activist Rachid Taha.

Essam's talk of equality for women and empowerment of the voiceless won widespread applause. “We’re with you all the way,” an octogenarian Canadian couple told him after he sang his 2014 hit Heyla, Heyla based on a poem about workers' rights by Bayram al-Tunisi, the famous late poet who wrote songs backing the 1919 revolution against British occupation in Egypt.

My cause is humanity and freedom and human rights… But I don’t like to be called a 'political artist' because it’s limiting

- Ramy Essam

But the songs he sings on his latest album Resala Ela Magles El Amn (Letter to the UN Security Council) are so unflinchingly political that one actually longs for a little more personal reflection.

The title track on the album is a letter from a “bleeding human” who writes: I might not understand all the words said on TV, but I know that the air of prison is heavy/ I might not know how to spell the word 'freedom', but I carry its meaning within me.

Segn Bel Alwan (Prison in Colour) offers a feisty hip hop duet with French-Algerian-Lebanese star Malikah and is dedicated to the Egyptian women imprisoned during the revolution, as well as their sisters around the world.

Essam does not have time to lose, it seems. This weekend he managed to squeeze in an on-stage music session with legendary British protest singer Billy Bragg - who spoke with him afterwards about a possible future collaboration - as well as two solo shows and several appearances jamming with myriad artists from the southern US to Central Africa.

For the children of Syria

Essam was enthusiastic while talking about his recent collaboration with English musician PJ Harvey, writing Arabic lyrics for her song The Camp. The piece is dedicated to Syrian refugee children with a video featuring images from a new book by photojournalist Giles Dudley called I Can Only Tell You What My Eyes See.

With haunting lyrics about "children who move like ghosts", the song and video document the lives of displaced children in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. Profits from the track’s sales go to the Lebanese NGO Beyond Association.

PJ Harvey was always on my dream list of artists to work with

- Ramy Essam

“PJ Harvey was always on my dream list of artists to work with,” he relates. So he was happy to learn that she was already aware of his work when his manager emailed her suggesting a collaboration. “She’s been travelling a lot in the Middle East lately,” says Essam, "and has become very aware of the regional situations.” When she suggested they work together on The Camp it seemed like “a perfect fit”.

But rather than fetishise the child refugees as victims, Essam chose to focus on their “dreams”.

Far from home

While Essam is physically far from the ongoing Egyptian struggle – partly because of his legitimate concerns for his safety and partly because of touring and recording commitments - he is never far from his homeland emotionally.

The song on his latest album El Horreya lel Geda'an (Freedom for the Brave), incorporates popular chants about releasing political prisoners. According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), Egyptian authorities arrested or charged at least 41,000 people between Morsi’s downfall in 2013 and May 2014.

HRW added in a report issued in September 2016 that an estimated 26,000 more may have been arrested since the beginning of 2015, according to lawyers and human rights researchers.

He wants to return soon, but he says his fans are still harassed by police if his music is found on their phones and that if he did try to perform it would have to be “totally underground – like ‘sing and run’”.

“I am Egyptian. I love my country,” he proclaims, citing influences like seminal late Egyptian composer and singer Sayed Darwish, the alternative band Nagham Masry and hip-hop artist MC Amin as Egyptian idols.

“But I’m not a nationalist. I just want my country to be good. I’m not asking for much. I just want homes for everyone, safety, education, healthcare - the normal basic human rights,” he added.

When reminded that these were late president Gamal Abdel Nasser’s promises too, he does not miss a beat. “Promises, yes, but look what happened. The whole reason we’re in this mess with military rule is because of him. Although he would be sad to see what his legacy has become.”

Many Egyptians compare former army chief Sisi to Abdel Nasser, the charismatic colonel who led a coup against the monarchy in 1952 and started an army-led autocracy.

I’m not a nationalist. I just want my country to be good

- Ramy Essam

For a moment I catch a glimpse of sadness in Essam’s eyes. But when I ask him what he thinks of the bromance between Trump and Sisi, the glint of resistance returns to his gaze.

“Actually,” he confides, “I was thinking of rewriting the lyrics to my hit song about Sisi – The Age of the Pimp - with a verse about Trump and Putin.”

Essam's nostalgia for the heady days of post-Mubarak Cairo is still palpable.

“From the fall of Mubarak in 2011 until midway through 2013,” he recalls, “it was an exciting time to be an artist in Cairo. You could perform everywhere – it was amazing. You could just go somewhere, build a stage without taking permission from the police, and just do a concert and make the people happy. But then it all disappeared,” he said.

“One day,” he relates, as the military replaced the resistance to ousted president Mohamed Morsi “we found ourselves, the independents, alone. We were not organised enough to lead the revolution. We didn’t have any kind of leadership – a person or a project to fight for. We were waiting for a saviour who never came.”

We were not organised enough to lead the revolution… We were waiting for a saviour who never came

- Ramy Essam

When military rule returned in the post-Morsi era, he says, “they censored everything like Mubarak had done before”.

One of his songs on the new album El Gahsh Wel Homar (The Donkey and his Son) – a conversation between a dictator and his son – was in fact written anonymously by a Mubarak-era poet, a common practice at the time. Today, the problem, he says, is self-censorship.

“When artists start to think twice about things before writing songs,” he notes, “this is a dangerous moment for a culture.”

An artist not an activist

The young singer was an architecture student in the town of Mansoura who dreamed of being a rock star, before the 2011 Egyptian revolution inspired him to write more strident songs of protest. His subsequent abuse by Egyptian military police – he was detained for eight hours on 9 March 2011 during a protest in Tahrir Square and tortured in the Egyptian museum as documented on 60 Minutes – only served to embolden his resolve.

I’m not asking for much. I just want homes for everyone, safety, education, healthcare - the normal basic human rights

- Ramy Essam

But after two years of playing and protesting throughout Egypt, and remaining fiercely independent in spite of overtures from the plethora of post-Mubarak political parties, his popularity declined in June of 2013. At the height of anti-Morsi sentiment, which Essam shared with thousands, he refused to embrace the military as an alternative.

A few days before Morsi was removed from power by the military coup in 2013, Essam sang a song against him titled Come on, resign. But with Essam’s refusal to support the military rule, his gigs dried up.

After Sisi was “elected” by 97 percent in May of 2014, Essam relates that he was stopped at a checkpoint by a police officer in Suez singing his song Taty Taty (Bow Your Head) in a sardonic tone. Armed with video footage of Essam performing an anti-police song in Tahrir Square, police held the singer overnight for interrogation.

With violent threats from soldiers on social media and in person, he relates, it seemed like an opportune moment to accept an invitation for an artistic residency in Malmo, Sweden, with ICORN (International Cities of Refuge Network) that was arranged via Freemuse, a nonprofit dedicated to the plight of persecuted musicians worldwide.

It’s so hard to demonstrate now in public, but we can still sing

- Ramy Essam

Today Essam divides his time between Malmo, where his three-year-old son lives with his ex-wife, and Helsinki where he is currently collaborating with a group of Finnish musicians. He has just recorded a new album with them that will be released in early 2018, featuring his usual rock style mixed with traditional Egyptian percussion instruments.

“Helsinki is an amazing place,” he enthuses. “My new favourite city. There is so much creative energy happening there.”

We can still sing

The real threat to the Egyptian regime, he says, is the “more than 50 million young people – people under 30 they can’t control or brainwash anymore like they used to, because of the internet and globalisation”.

“Artists are their only hope – culture the only tool that can show them the way. It’s so hard to demonstrate now in public, but we can still sing," he said.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.