'Get out and tell the world': Marie Colvin's life and death in Syria's war zone

BEIRUT, Lebanon - When photographer Paul Conroy and the UK's Sunday Times veteran war correspondent Marie Colvin decided to turn back in the tunnel that was taking them out of the Baba Amr district of Homs, Syria, they knew they were taking a huge risk.

It was 2012, and that year alone would claim the lives of more than 120 journalists covering hostilities in Syria. The Baba Amr district, where at least 20,000 civilians were trapped, was under heavy bombardment by the government forces of Bashar al-Assad.

Few Western journalists were still on the ground due to the extreme danger. The decision to stay in Baba Amr to bear witness to the facts proved fatal for Marie Colvin and French photographer Remi Ochlik, who were killed on 22 February by an artillery shell that struck a makeshift media centre.

Just because we do not see an immediate result [from the pictures and reports in Syria] does not mean we should stop

- Paul Conroy

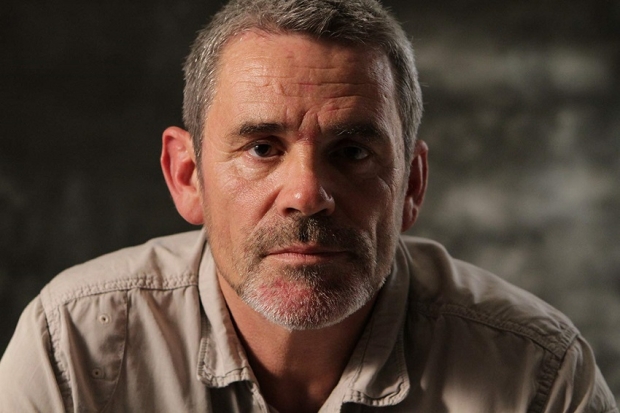

For Conroy, Colvin's friend and colleague, who narrowly escaped death himself in that shelling, the importance of telling the world what is happening in Syria by reporting from the ground remains vital today.

"Just because we do not see an immediate result [from the pictures and reports in Syria] does not mean we should stop. Our work as Western reporters does have an impact," he tells Middle East Eye.

Conroy has spent his time recovering, having had to undergo 23 operations on his leg, and working relentlessly on his book Under the Wire, written over a six-month period after he left hospital in August 2012. In September, it was released as a documentary directed by Chris Martin.

Under The Wire recounts his testimony of the horrors and realities of conflict zones and looks at his friendship with Colvin, combining new interviews of Conroy and other people involved in the story along with not-previously seen archive material.

Marie's humour: the last conversation

Conroy explains that there were so many layers to Colvin's character that attempting to describe her is as difficult as trying to catch fresh air.

I thought to myself: goodness she already lost her eye, now her hearing?

- Paul Conroy

"I thought to myself: goodness she already lost her eye, now her hearing?" He used the light on his phone to examine her ear: a rubber bud from the little headphones she had used during the interview had remained stuck. "We started laughing hysterically. We could not stop. Even the next morning when we got up, when our eyes crossed we would start laughing." This was the last proper conversation the two journalist friends had.

Humour, which Colvin was notorious for, was a way to survive. The Hollywood film A Private War, which portrays her life and career, has been praised by journalist friends of Colvin's, particularly for Rosamund Pike's performance of the seasoned journalist. Unlike the documentary Under the Wire, Conroy was not involved in the Hollywood picture.

Conroy, praising the snapshot the movie captures of Colvin, notes the challenge of fully showing the different layers of her character. "The movie is very good, and it provides detailed anecdotes of different moments of her life and career," he says.

From northeast Syria, where the two originally met, to Iraq and Libya, Colvin and Conroy shared numerous war reporting missions. They had learned how to make the best use of their complementary roles and personalities.

At roadblocks, they had developed an innate sense for who would be best equipped to do the talking. "I'll take this one" or "it's best if you take this one," Conroy explains to Middle East Eye. It depended on the situation: sometimes being a woman in a conflict zone could prove to be "disarming". Sometimes taking people by surprise could work to their advantage, but it was not always the case.

War reporting: it's about the people

Above all, Colvin's ethics and storytelling was what made her an extraordinary reporter. She cared about people and saw her role as giving them a voice.

"She earned the respect of the people," says Conroy. In Baba Amr, he notes, when the two journalists returned on their second and fatal trip, he noticed a significant difference in the way the civilians on the ground treated them. "People would see we were risking being there, and we could see they respected this."

She earned the respect of the people

- Paul Conroy

For documentary director Martin, this aspect became apparent when searching for video material from Homs for the documentary. People were helpful in providing information and video once they realised it was about Marie.

Describing the conflict in Homs in the documentary, Conroy states: "It was not war, it was a slaughter." Having witnessed many conflicts both as a former soldier in the British Royal Artillery and war photographer, he says what he saw in Syria was entirely at a different level of destruction.

A Red Crescent ambulance offered to take him and French journalist Edith Bouvier out of Baba Amr. Then the head of the ambulance team, whose identity Conroy does not mention to protect him from potential repercussions, told everyone to exit the room they were in, leaving only the foreign journalists there.

It's the hunger for storytelling that drives journalism. No one is in this business for the money

- Paul Conroy

That is when he told them, as recounted in the documentary, "do not get into that ambulance. If you do, you will be executed and your bodies will be thrown on the battlefield and they [the Syrian government] will say you were attacked by the rebels."

Conroy took the advice and stayed put until five days later, when local activists smuggled him out. It was a long trip on a motorbike - with his wounded leg - out of Homs and into the Lebanese mountains.

It would be two years before he could walk properly again, and he is to this day still undergoing physiotherapy.

Conroy always asks himself: "What could I do better the next time?" Six years after that fatal reporting mission in Homs, he stresses how his dedication to keep telling the story of what is happening from the civilian side that he witnessed has also helped him face the trauma of all that he saw and experienced.

The claim is that Colvin's reporting challenged the Syrian government's narrative that it was fighting terrorists, while for Colvin and Conroy there were only civilians being attacked, and this determined their objective to silence them.

The case against the Syrian government reached court in April this year with evidence from Syrian defectors and is one of the first cases seeking to hold the government of Bashar al-Assad responsible for war crimes.

Criticism and 'fake news'

After six years, with at least 500,000 Syrians killed in the war and another 5.6 million forced to seek refuge abroad, Conroy insists still that there is no substitute for reporting from the ground.

It was not war, it was a slaughter

- Paul Conroy

The news industry is challenged from numerous perspectives today. Firstly, for journalists, it has become increasingly dangerous to report. Journalism is under pressure, not solely because reporters have often become physical targets but by the issue of "fake news" and how to counter it effectively.

"It's the hunger for storytelling that drives journalism. No one is in this business for the money," he comments. For him, both himself and Colvin were driven by this urge to cover war zones, not by the war buzz.

Conroy and Colvin were smuggled into Homs by rebels from the Free Syrian Army and were subsequently considered spies by the government of Assad. He has not been back to Syria since 2012. "I have a 'wanted' sign over my head. I cannot go back."

Commenting on how the war has evolved since 2012, he notes "on behalf of the Syrian side I met, concerning what lies ahead in Idlib, I believe under no circumstance would the people there accept a peace with Assad still in power. They expect for the regime to be held accountable."

For Conroy, Marie Colvin died telling the truth, and the documentary, Under the Wire, continues this legacy when towards the end he is smuggled to safety, with the people left behind saying to him, "Get out and tell the world."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.