Gold sabres and iron shackles: A Libyan display of hope and despair

MISRATA, Libya - On Misrata's Tripoli Avenue there are still houses without walls, and walls without roofs. Sheets struggle to cover craters in facades, but little can be done about those staircases that lead to nowhere. There is also a most peculiar cafeteria where the locals smoke water pipes under the shade of a balcony that hangs at an impossible angle. That, they say, was once Misrata's only Spanish restaurant.

As if the scars along Misrata's main artery were not already a powerful enough reminder of the 2011 war, there is also a huge collection of war trophies on display outside the Museum of Martyrs. Mortar grenades line up alongside rocket launchers, the remains of yachts and even a spray paint can is available in case anyone wants to scrawl their signature on a tank. Still, the most precious war trophy is the iconic sculpture of the golden fist squeezing an American fighter jet. Muammar Gaddafi would often give his speeches next to it from his bunker in downtown Tripoli.

The open-air part of the museum can be enjoyed any time, but patience and, eventually, a bit of luck are needed to get inside.

"We used to open every day but now [it's] just two or three times a week, and there's no fixed timetable," said Adel Swaisi, who mans the reception desk. In the past, Swaisi, a university level chemistry student, would get around 300 Libyan dinars monthly (around 50 euros in the black market rate), but the money stopped arriving long ago. Still, for Swaisi, this is much more than a job.

"The museum opened on 24 April 2011, just when the city was liberated. All the people you see on the walls are Libyan martyrs; you'll find more than 4,000,” noted Swaisi, referring to the myriad portraits covering the partitions. The portrait of his father, who was killed in 2011, can be found on the right wing of the enclosure, but many others had to make do with their portraits flashing up momentarily on a plasma screen once the walls ran out of space.

"God is the greatest" repeats a litany, while the faces of those who died when the partitions were already full are projected one after another. Swaisi said that a third of those honoured here were from Misrata. It is impossible to verify such figures because of the lack of an official census but, looking around, it might not be that far-fetched.

In 2011, Misrata endured a brutal two-month siege by troops loyal to Muammar Gaddafi. Later, local militias also took a leading role in fighting in 2014, in what has been labelled Libya's second civil war, which led to the emergence of two rival governments and parliaments: the Tobruk-based House of Representatives in the east and the Tripoli-based General National Congress in the west.

A third administration, the Government of National Accord - this one backed by the UN - would literally disembark in Tripoli in March 2016 with its leader, Fayez al-Serraj promising to "turn the page" despite opposition to its authority from the two rival parliaments.

Misrata's armed groups became the latter's battering ram in the fight against the Islamic State (IS) group in its stronghold in Sirte. Several of the more than 700 hundred people killed in this last war are already remembered here, albeit on the plasma screen. The crucifixion set used by IS militants outside the building also pays witness to Libya's last front.

Four weapons per capita

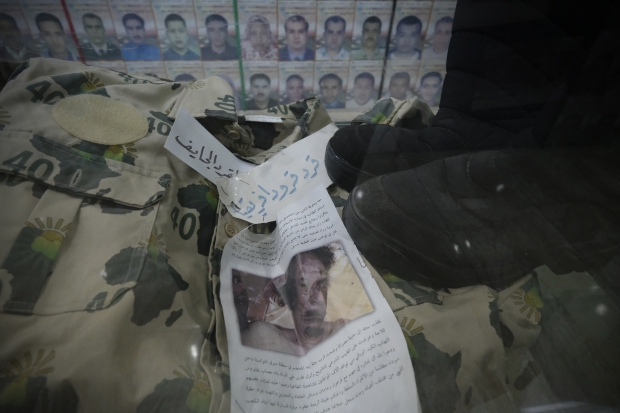

Ramadan Dolah, Swaisi's co-worker at the museum, offers a guided tour across one wing where all sorts of goods belonging to Gaddafi are piled up in glass boxes: gold sabres and iron shackles; his boots and his uniform, especially made for the 40th anniversary of his rule. Right next to those one can spot ancient rifles and even handmade weapons used by Misratis during the two-month siege.

“I know people who fought with rifles dating from the Italian period of rule [1911-1947],” said Dolah, pointing to a sample under a glass box. Next to it lies a set of Molotov cocktails, and even a “bullet-proof” vest made with the remains of a blind.

“All this may look too rusty, but believe me when I say ours is Libya's safest city,” said the volunteer worker with pride.

It is true that Misrata enjoys significantly high levels of security by current Libyan standards. Walid Mohamed Abu Sela, captain of a police squad that patrols the streets every night, points to a "compact social fabric” behind the relatively safe environment.

"Both Tripoli and Benghazi - Libya's main cities - host people from all over the country and from almost every tribe, but here we are all from Misrata, we all know each other," the officer told Middle East Eye at the end of a peaceful night patrol during which the only incident had been a drunk driver.

Security, however, is a rare privilege in post-Gaddafi Libya. Last September, Martin Kobler, the top United Nations official in Libya, called for more to be done to halt banned arms shipments. “Libya has 26 million weapons and a population of six million,” Kobler said during his speech at the Human Rights Council at the United Nations in Geneva.

'Libya has 26 million weapons and a population of six million,' Martin Kobler, the top United Nations official in Libya, said during his speech at the Human Rights Council at the United Nations in Geneva

More than five years after Muammar Gaddafi was killed by rebel forces in Sirte - Gaddafi's hometown - when they took control of the city, civilians continue to bear the brunt of the conflict. According to a recent Amnesty International report, 435,000 individuals are internally displaced, with more than 100,000 of those residing in makeshift camps.

Bankruptcy

One of the most striking elements among the artefacts on display is a set of photocopied bank notes. “During the 2011 war we'd often come across them in Gaddafi's army barracks. Apparently he was paying his mercenaries with photocopies,” recalled Dolah.

“It's not that different today, is it?” said Ahmed, a man in his early fifties who happens to be one of this afternoon's few visitors. The collapse of Libya’s currency, with a rate of eight dinars to a euro in the black market – it was one to one in 2011 - has pushed Libyans toward economic meltdown. Libya is very much a cash culture, but banks are currently putting a limit on what Libyans can withdraw.

The collapse of Libya’s currency, with a rate of eight dinars to a euro in the black market – it was one to one in 2011 - has pushed Libyans toward economic meltdown

“It's not only about the devaluation of the dinar and the cash shortage,” adds Ahmed, “you also have to watch your wallet before you travel elsewhere in Libya as many bank notes are not accepted in certain parts of the country.”

Ahmed is right. The old one dinar notes boasting Gaddafi's portrait are still accepted elsewhere in Libya, but not in Misrata. Besides, Libyan bank notes printed in Britain are only accepted in the western Tripolitania region, while the eastern part of the country sticks to those made in Russia.

Libyan currency is printed abroad to avoid counterfeiting and to meet international standards. The Nafusa mountain range, in the country's northwest, might well be the only place where no distinctions are made. “Russian” money is flown in via Zintan - an Arab enclave aligned with the east - only to flow later through their Amazigh neighbours' pockets despite the latter being administratively linked to the west.

The Museum of Martyrs, however, is far from being out of touch with Libya's economic conundrum. Swaisi and Dolah explained that funds have always come from private donors, often relatives of the fallen or Libyan individuals who, according to Dolah, "vow to keep the memory of the revolution alive," but those are diminishing, according to the museum keeper.

“We are ready to work for free, but still we need some money to keep the place open, you know?” said Swaisi, before giving us a DVD as a souvenir. It contains almost three hours of footage of the most relevant moments of the 2011 war: from the first demonstrations in Benghazi to the killing of Muammar Gaddafi by Misrata fighters. There are also images of people embracing and jumping in joy, celebrating the beginning of a new era.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.