'I cannot leave my people to die here': Aleppo's last citizen journalists

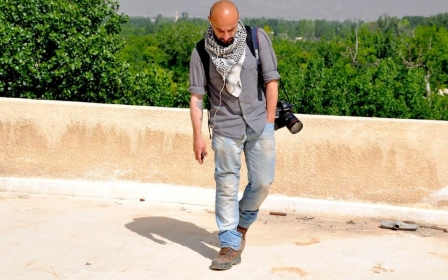

Citizen journalist Faddi al-Halabi is 24-years-old and has worked in Aleppo since 2011. His photographs and footage can be seen on many news outlets worldwide, including Reuters, AP Archive, Ch4, BBC, Sky News, the Aleppo Media Centre and others. This is his story as told to Salwa Amor in London.

From a very young age, I grew up helping my father in his furniture store as well as studying at school, and then college. When the revolution first started in early March 2011, I took part in protests with all of my friends. Because of that, I could no longer keep up with my work or my studies, so I left both and began filming the revolution in July 2011.

It is hard to believe, but Syrian state TV actually took footage of an anti-leadership protest and broadcast it as if it were a march in support of President Bashar al-Assad. I was at a protest the following day when I heard people chanting: “Liar, liar, liar, the Syrian media is a liar.” That was the first time I took out my phone and began to film. In that moment, all I knew was that I wanted desperately to show the truth of our protest. I felt my camera was my own weapon to fight against the government's lies.

I wish that our country had an honest and transparent news outlet that would relay what was happening on the ground on a daily basis, but sadly that is not the case.

It was an amazing beginning to the revolution in those early days. I would join in the protests and film using my mobile phone and then upload it onto YouTube later to allow others in Syria to see what was really happening in Aleppo. It mattered to us in Aleppo that the rest of the country knew we were also part of the new wave of protests that was taking place in Homs, Deraa and Damascus. It was important that they saw we were all taking part.

We would delete the footage from our phones after uploading it online as a precaution. If you were caught by the government and had such footage on your phone, you would never see the light of day again. I have many friends who were arrested for filming the protests of 2011 or for having protest photos on their phones - some were killed while being tortured. There was a real fear of being caught.

Sadly, the Syrian Electronic Army - a pro-Assad online hackers group - found our YouTube channel and hacked it, deleting all of our videos from the early days.

You cannot ignore the screams

The residents of Aleppo have come to know our filming teams well. Many know us by name and when you arrive at a scene of devastation and people scream your name. Of course, you put down the camera and run to them. The hardest thing you could ever imagine is hearing the screams beneath the rubble, when people are calling you, begging you to rescue them, but you cannot get to them.

I remember one day that I was filming moments after a Russian jet hit a residential home, and I could hear a voice beneath the rubble calling out to me. I tried to remove some bricks and heavy debris, but it was futile, as the voice began to fade and then disappeared altogether after half an hour. I stood there feeling crippled. That was the hardest day.

There are many occasions when the rescue team - The White Helmets - does not get to emergency situations in time, and we journalists have to take people to the hospital, or help with the rescue mission. It is just part of being one of the first people on the scene. Many friends of ours have died this way, either in a secondary explosion or while trying to rescue people from an actively collapsing building.

This past April was the hardest period in the last five years. For endless days and nights, government and Russian jets did not leave our skies - every area was being hit. No matter where you went, there were injured people screaming, blood was just everywhere, and lifeless bodies were strewn around an Aleppo I could no longer recognise.

I began to remember the numerous friends that lost their lives and how people will never know about them, and I started to feel that it would soon be my time too. My greatest sadness was that I would die like them, another number and a forgotten face; just like the endless victims I see everyday.

'I cannot leave my people to die here'

No matter how dangerous things are, or how much it escalates, I can never leave my hometown. I could live outside Aleppo and my body would survive, but my soul would die and my conscience would torture me to go back. I cannot leave my people to die here as numbers on a list of casualties, with no one knowing what happened to them or hearing their stories.

I could leave and become a refugee, but there are people here who are dying and there are no international journalists in Aleppo, not a single one that I know of, so we have to work extra hard to fill the gap. If there were journalists here, of course, I would not be doing this now. I would have chosen a different path in life, but the revolution chose this path for me.

If I am not going to make a sacrifice for truth, who will? This is our country. Aleppo is my hometown. It is not a hotel that I can just walk out of. Its streets run in my veins and I must let the world know that there are people here being slaughtered. There are families with nowhere to live and there are people with nothing.

I choose to be part of the revolution because we have been oppressed for a long time. Our country should be much better than it was. And so I cannot leave it now, after it has become harder because we are the ones who called for freedom and dignity, and we will remain until we get it.

There is something tremendous about staying behind with the people to document their suffering. Even if I do die, it will not be for nothing.

On 30 April Fadi wrote on his personal Facebook under the hashtag #Aleppoisburning:

“I know very well that I will not survive this holocaust. I feel as though death is besieging me, as though I am a body without a soul, a heart without a beat…”

Louai Barakat

Louai Barakat is a 25-year-old citizen journalist who has reported for Al-Jazeera, Orient, BBC, Reuters and Alburaq Media. This is his story as told to Salwa Amor in London.

My filming began in mid-2013 with the FSA, and then I moved on to professional work, supplying several international news networks with footage and reports.

I remember my first day of filming. It was a Friday and Assad began shelling the area and chaos ensued. Families were running out of their homes and running away. Only the FSA remained and I stayed because I needed to. I did not want to run. I desperately had to make sure that I was not the only person seeing this atrocity. So I picked up my phone and began filming. In this way, I knew that it would not only be me seeing what was happening because the camera allows the whole world to get inside Aleppo. I wanted the world to be a witness.

I used to take part in the protests during the days of what we now call, "the peaceful days". We would chant and hold banners that called for basic principles such as freedom and non-violence. We just wanted freedom of speech back then, to be able to have our voices heard.

I was arrested during one of those protests and was taken to the government's Damascus-based Kafr Sousa secret service (mukhabarat) prison.

During questioning, I initially denied that I had taken part in any protests. Then one guard told me that if I were to admit to it, they would not have to hurt me... so that is what I did. He then beat me savagely with a metal bar and asked me to tell them the names of others who were in the protests - I did not. One guard who was smoking a shisha pipe, took the coal and burnt my leg with it.

I shared a prison cell with old men who were political prisoners from the 80s. The torture I witnessed there is impossible to even describe. I thought I would never leave the place alive. But sometimes I would sit and think to myself: “If I ever leave here, I will be a thorn in the government's side. I will expose them and tell the world everything that is happening to my people!”

Only a few journalists left

There are more atrocities committed in Aleppo than there are journalists to cover them. There are only a few of us remaining now.

I covered 90 percent of the events that took place in Aleppo during the heaviest bombardments yet. This April and May were filled with massacres committed by Russian and government air raids on residential areas. I filmed the bombing of the al-Quds hospital, Masakin al-Fardos, and Bustan al-Qasr.

The al-Quds hospital massacre was the worst day for me.

I was on my way to buy bread when I first heard the fighter jets above. The area hit was very close to me, so I ran home to get my camera and rushed towards the bombing. The first strike hit near the al-Quds hospital. The plane left and then came back and another two rockets struck directly onto the hospital wall. Wherever I looked, I saw dead bodies and people burning alive.

My mind went blank. The horror of the situation made me lose sight of reality and any sense of time. I only realised I was still holding my camera when the rescue team was leaving and I had to leave with them.

What makes me stay and do this work is knowing that in every revolution there are those who take advantage of the situation and those that try to get to the top. I still have a role to play inside. There are many journalists who have gone, but there are many of us who refuse to leave. I will never leave.

I do not run from any shelling because I consider myself dead, no matter what I do, so I insist on filming it.

There is something inside me driving me to film what I see and document war crimes; Assad's endless bombing campaigns where countless civilians fall victim to one man’s death grip on power.

I wanted to be part of our great revolution, but I did not want to pick up arms. I wanted, instead, to be alongside my people and be one with them. Whatever is to happen to them, will happen to me; the only difference is I have a camera. I will show what was happening to them, to us, to our country.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.