‘I still cry every time I hear her name’: Rabaa families struggle to move on

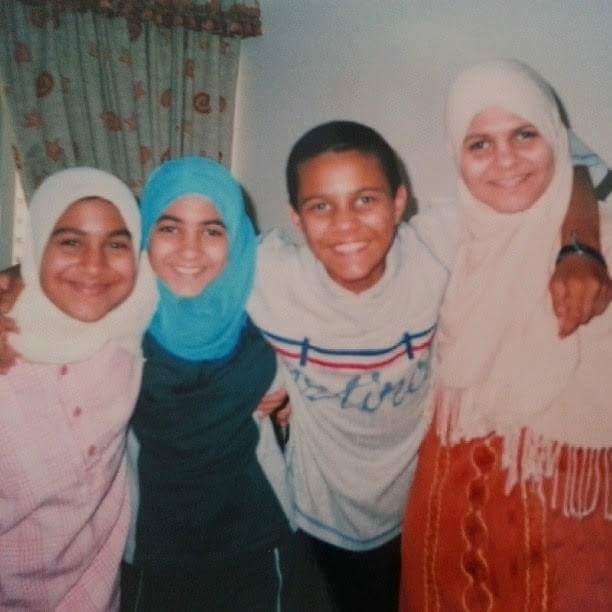

Three years ago to the day, 26-year-old journalist Habiba Abd al-Aziz picked up her camera and went to cover a sit-in outside the Rabaa mosque in east Cairo that had been protesting the overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi.

For weeks, tens of thousands of people had gathered there peacefully to voice their opposition to the coup that had taken place the month before, but on that fateful day the security services stepped in to disperse the crowds.

Aziz, a journalist for Xpress, the sister publication of the UAE-based Gulf News, had flown back to Egypt two weeks earlier to film the protest and as the police began to fire at the demonstrators, she took out her phone and started texting her mother to let her know what was going on. It would be the last time that her family would hear from her.

As Aziz tried to get to the front to see what was happening, a sniper put a bullet right in her heart. She fell where she stood, her video camera capturing the last moments of her life.

For hours her mother rang and rang, but got no reply, Habiba's younger sister Yara told Middle East Eye on the third anniversary of the massacre.

“Suddenly, a guy answered her phone and told her that she had been shot and was in Tiba Mall (the eastern entrance to Rabaa Square), and that someone should come and take her.”

Yara says she had a bad feeling when she got up that morning and couldn’t shake the sense of dread.

“I didn't want her to go, but I couldn't ask her not to. She's always had a strong sense of social responsibility, she always fought for what was right,” she said. “She always loved helping others; she lived for it."

According to Human Rights Watch, at least 800 but probably more than a thousand other families across Egypt would have received similar phone calls that day telling them that their loved ones had been killed. Three years on, few have been able to put their lives back together.

"Habiba was the one who paid for my university education,” Yara said. “She always wanted to see me graduate. I cried myself to sleep the night before my graduation. I cried the whole time I was getting ready. I cried on the way there.”

Yara says that since her sister’s death her family has stopped doing many things they would once do together because it is just too hard to do it without Habiba and brings back too many memories.

“Watching certain movies in the cinema, playing certain card games, certain Eid traditions…all of these things I can no longer do them, it’s like there are huge chunks missing,” she said.

“Even hearing her name is not easy. Once I was praying, and I heard someone calling Habiba, a father calling his daughter, and I froze and just couldn’t move. Another time, I went to an engagement party for a girl called Habiba and when someone asked me who Habiba was to me, I just froze.”

No justice, no closure

The loss has been made much worse for many families who say they feel that they will never see those responsible brought to justice. Since the Rabaa massacre took place, the new authorities have clamped down hard on anyone with alleged links to the Muslim Brotherhood since Mohamed Morsi's removal in 2013. Tens of thousands of alleged Brotherhood supporters have been imprisoned. Some have been tortured, others have been forcibly disappeared.

The authorities have in general been dismissive of the mass deaths caused at Rabaa and relatives say they feel officials have gloated over the mass killings.

"I resent myself for not calling Habiba and hearing her voice,” Yara said. “I resent those who made this possible. I resent the person who pulled the trigger. I resent those who gloated as my sister was dying."

Other families, however, have not even been able to find out what happened to their loved ones. UK-based watchdog the Human Rights Monitor estimates that as many as 400 people remain unaccounted for since the crackdown at Rabaa and a number of smaller protests that were happening across Cairo and the country.

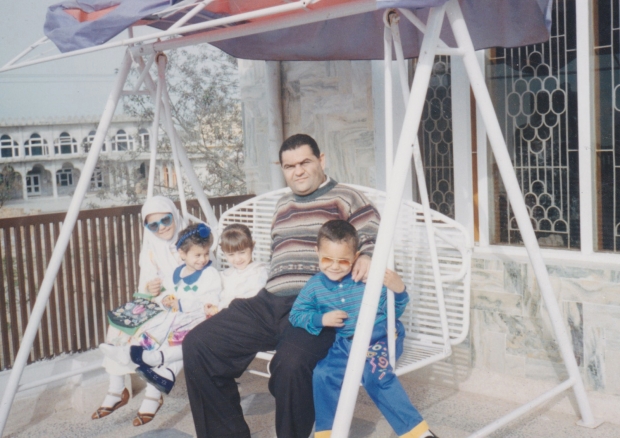

"He went, and never came back. We never found his body, we never found his name in any detention facility, it's almost like he never existed," the mother of Mohamad Khedr, an engineering student who has been missing since the Rabaa massacre, told Middle East Eye.

"I miss him so much, and I feel so helpless. It's been three years, and I still don't know anything about him. I don't know if he's dead or alive.

“I didn’t know that would be the last time I’d speak to him,” she added.

The memories of all those people who have been killed or have gone missing still haunts Omar, a doctor who was volunteering at the field hospital.

As more and more injured were brought in relentlessly, Omar - who did not want to give his full name for fear of political reprisal - said that the staff found themselves totally overwhelmed.

“No matter how fast we tried to work, there was just too much,” he said. “You work in auto-pilot in these moments, you start calculating which injury is too severe for you to be able to do anything about, and which injury is not as life pressing.

“You don’t dare think even when the bodies are familiar faces, because you know if you thought about it, you will lose it.”

According to human rights groups and survivors, the bloody crackdown started very early that morning when security services closed off the entry points to the square. They proceeded to start firing live ammunition into the crowd. Once people started falling, police started setting fire to tents, scorching the bodies and burning the injured. Soon thereafter, bulldozers were rolled in to demolish the tents. As they made their way through the square they trampled everything in their wake – crushing bodies and abandoned belongings alike.

“There was no room to move, by 9am every inch was covered, you couldn’t move for fear of stepping over a body, whilst more and more injured were being carried in,” Omar said.

“Before, there were tents and sleeping bags every step of the way. When I stepped out at midday, everything was torched to the ground, it was like the square had become a piece of charcoal.”

“They [the police] began firing directly into the hospital and we [the doctors] were ordered to leave. We told them there were many injured, dozens in each room, but the officers wouldn’t listen and ordered us to either leave them or join the rising pile of dead bodies.”

Once the doctors were moved out, the police torched the makeshift medical facility.

Things you can't unsee

“You can’t unsee some things, you could never forget the stench of charred skin that steeped in and clung to you for days and at times, feels like it never left,” Omar said.

Omar says he physically tried to scrub himself clean for months afterwards, in a desperate attempt to erase the memory of the dead, but that no amount of cleaning ever really helped.

Ahmed Assem was another journalist who was to lose his life that day.

"We used to call him Hazelnut,” his friend, Nour Kashef, said. "He was the first person I know to die. I cried myself to sleep that night."

"I thought that the news of Hazelnut was the worst and that it couldn't get worse. But when the news of Habiba came, the shock was like nothing I've ever experienced before. Habiba, Habiba who had not even been in Egypt two weeks ago was dead."

That day, every half an hour, a friend of mine was killed, Kashef said.

"Deda, Ahmed Deya, who was older than me by a year only, was killed. Then Ahmed Sonbol. Islam Kinawy. Ahmad Ammar. Mohamad Abdelbaset. Asma Sakr. The news came quicker than I could process it. I walked through the roads, roads heavy with smoke, blood and burnt black. All the tents, the people, the shops, the food, everything, everything was burnt, the world had turned to ashes."

“In the beginning, I just wanted to die in any way but now I need their justice first.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.