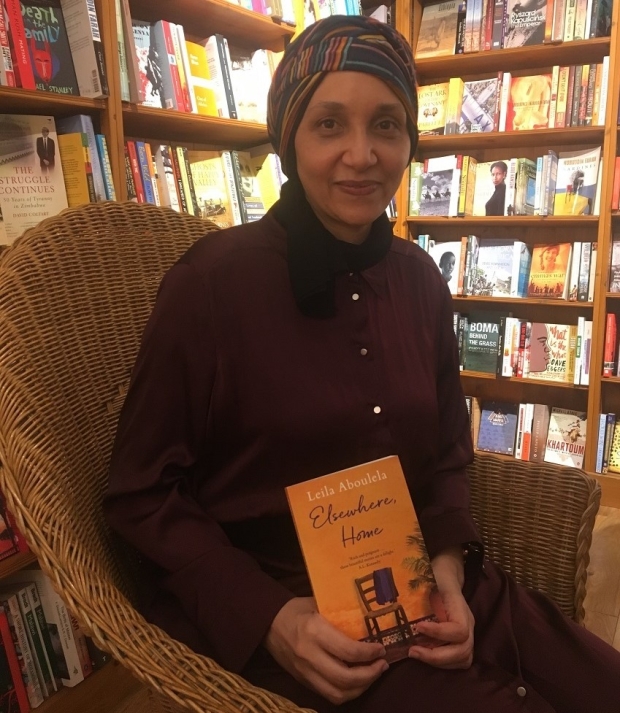

'I still feel the need for resistance in my writing': Sudanese author Leila Aboulela

Award-winning Sudanese novelist Leila Aboulela knows what it means to leave one world behind and embrace a new existence with courage and determination. With her roots laying down the foundation for her craft, Aboulela's works of fiction focus on the exploration of identity, migration and spirituality.

“It seemed that the fate of our generation is separation, from our country or our family,” she writes in Coloured Lights, the first story featured in her new collection of short stories, Elsewhere, Home.

Elsewhere, Home was released on 2 July after its launch at the Africa Writes Festival on 30 June at the British Library. The book, which has already been longlisted for the 2018 People’s Book Prize, features 13 brilliant short stories, some written two decades ago, some very recent.

Aboulela's latest book includes stories of nostalgia for Africa and the Middle East, the struggles of being a woman and a mother, the anxiety of immigrants raising children in the West and the loneliness of being a Muslim in a western country. The stories show subtle intertextuality, linking them together in a delicate way.

Longing for Sudan

While the book is not autobiographical, the stories were influenced by Aboulela's personal experiences.

The protagonist of Coloured Lights is a homesick Sudanese girl on a London bus remembering the events that led to her brother’s death on the eve of his wedding.

The Ostrich is the story of Samra, a pregnant woman reminiscing about her youth in her country of birth. She is married to Majdy and they are both Sudanese, but they do not feel the same way about their home country. While Samra has strong nostalgia for Sudan and finds comfort in reminiscing about her life there, Majdy relishes in the "modernity" of the West and constantly belittles the "backwardness" of Sudan.

“I can’t imagine I could go back, back to the petrol queue, to computers that don’t have electricity to work on or paper to print on. Teach dim-witted students who never held a calculator in their hands before,” Majdy says in the book.

But to Samra, Europe is dull and lonely: “Here in London, the birds pray discreetly and I pray alone. A printed booklet, not a muezzin, tells me the times.”

I’m writing about the people that I know, about the world I’m familiar with, the circles I move in

- Leila Aboulela, award-winning novelist

In Coloured Lights immigrants and their children are constantly faced with the notion of "gratefulness", as if their mere presence in the West means they have been "saved" from the evil and downfall of their "backward" home countries.

"You are envied, Samra. You are envied for living abroad where it is so much more comfortable than here. Don’t complain, don’t be ungrateful," Samra's mother tells her.

These are not typical narratives. The characters are neither heroes nor villains, which is refreshing because Muslim immigrants are seldom depicted in such a non-problematic, banal and truthful fashion. The protagonists are easy to identify with because the writer chose to represent reality, rather than a fantasised depiction of Muslims.

“I’m writing about the people that I know, about the world I’m familiar with, the circles I move in,” she says, “I’m just reflecting what is naturally in my life, rather than consciously making a point of representing. It would actually be harder for me to write about non-Muslims. I can do it of course, I can research and so on, but this comes more naturally to me.”

Success and the halal novel

Born to a Sudanese father and an Egyptian mother in Cairo in 1964, a few weeks after her birth, Aboulela's family moved to Khartoum. She moved to London in her mid-20s and studied at the LSE before moving to Aberdeen in Scotland in 1990 with her family. There she worked as a lecturer at Aberdeen College and as a research assistant at Aberdeen University.

Aboulela has written four novels, two collections of short stories and several radio plays. Her work has been translated into 14 languages, and she has been shortlisted for and won several literary prizes, including the Caine Prize for African Writing for her short story, The Museum, which is also included in Elsewhere, Home. Three of her novels (The Translator, Minaret and Lyrics Alley) were shortlisted for the Orange prize and Lyrics Alley won the fiction prize at the Scottish Book Awards.

The status quo will always assert that western, white and secular is the norm and that everything else always has to explain itself - Leila Aboulela, award-winning novelist

Aboulela's first novel, The Translator, was published in 1999 and was listed in the New York Times as being one of 100 Notable Books of the Year.

According to Aboulela, The Translator’s female protagonist is a “Muslim Jane Eyre,” and Riffat Yusuf of The Muslim News, a digital monthly newspaper based in London, called the novel "the first halal novel written in English".

The Translator is about Samar, a Sudanese widow working as a translator in Scotland who falls in love with Rae, a Scottish academic.

Souvenirs is my first story set in Scotland, and the main character works on the oil rigs in the North East, and this is what my husband actually used to do and why we moved to Aberdeen

- Leila Aboulela, award-winning novelist

"Souvenirs is my first story set in Scotland, and the main character works on the oil rigs in the North East, and this is what my husband actually used to do and why we moved to Aberdeen,” she says.

In the story, Expecting to Give, a pregnant woman finds herself alone when her husband leaves to work offshore in the oil rigs. Aboulela experienced similar circumstances when her children were young.

“There is the element of autobiography because there are things I experienced, and things that I completely made up,” she adds.

A white, male perspective

However, the second story of the collection, Something Old, Something New, features a white, male protagonist, a Scottish convert to Islam who falls in love with a Muslim Sudanese girl and who follows her to Khartoum to marry her.

“I wrote this story after I had been writing for some time, it was sort of mid-career. I decided to take a risk with writing from a male point of view and from a white Scottish perspective,” Aboulela explains.

In Coloured Lights immigrants and their children are constantly faced with the notion of 'gratefulness', as if their mere presence in the West means they have been 'saved' from … their 'backward' home countries

“This is a Scottish man travelling to Sudan and seeing the country from his own eyes. I wanted it to be realistic, and I thought that was how he would see Sudan. I thought it wouldn’t be realistic if he didn’t have this type of prejudice," she says.

Aboulela adds that Sudanese author Buthayna Khidr Makki inspired her to write this story. According to Aboulela, after Makki read The Translator, he told her, "you could have gone on more, about [the Scottish academic] and about Sudan and about what he did next, you kind of stopped short of that".

Something Old, Something New is one of Aboulela’s favourite stories in the book along withThe Ostrich and Pages of Fruit.

"Pages of Fruit is the last story I wrote, so I also like that one very much. As a writer you always like the last thing you’ve written. You always want it to be the best.”

A voice for the marginalised

Aboulela first started writing in the 1990s at a time when issues of racism and white privilege were not yet popularised or mentioned much in the media.

I decided to take a risk with writing from a male point of view and from a white Scottish perspective

- Leila Aboulela

Today she says these notions have now moved closer to the mainstream and people are speaking about them more, but it is still not enough.

“We can argue that things are better or worse. You can look at it in different ways, but it’s still there,” Aboulela says.

She asserts that she still feels the need for "resistance" in her writing.

“I think this is really the ground I’m still standing on, the need is always there. This book of short stories covers 20 years of my writing," she says. "Of course there have been huge changes in these ideas of ‘Islam vs the West’ or ‘Africans and immigrants in the West.'”

She maintains that it is still necessary to present issues from the point of view of immigrants, Muslims, the oppressed and marginalised, “because the status quo will always assert that western, white and secular is the norm and that everything else always has to explain itself”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.