Jailed for a joint: Tunisia's drug law throws thousands into hellish prisons

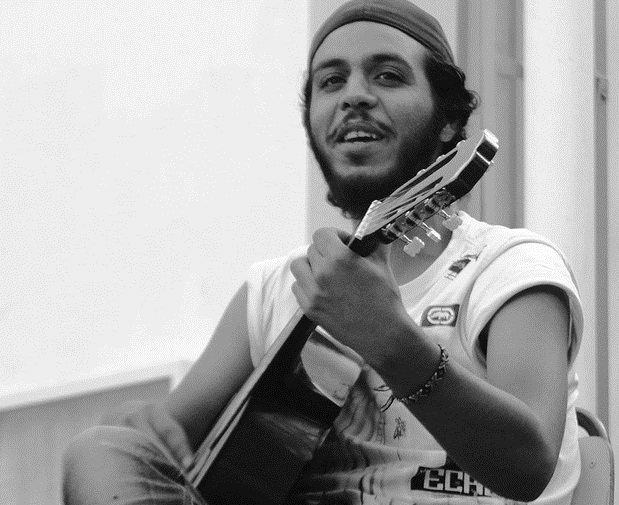

TUNIS - Seif Matmani was a young musician with dreams of success when a pack of cigarette paper found on him by police led to his arrest.

“A dozen policemen jumped on me when I walked in the street after I went out to buy rolling paper at the tobacco shop next to my parents house,” the 27-year-old guitarist told Middle East Eye, while drinking black coffee in a cafe in downtown Tunis.

'I didn’t imagine I would go to jail so easily. I didn’t hurt anyone around me, so it seemed absolutely crazy'

The young man, who holds a Baccalaureate degree in tourism, talks about how his life was put on hold one night in December 2014.

Police searched him and found the rolling paper, and then arrested him and took him to the police station where they found cannabis in his wallet.

Matmati did not smoke on that day, but he was a regular marijuana consumer. So he chose not to resist the police’s demand for a urine test, which can determine if a person has used drugs up to three months after someone's last drug use, according to Matmati.

“It was positive," said Matmati. He was subsequently sentenced to one year in prison, under Tunisia’s drug legislation, Law No 92-52.

“I didn’t imagine I would go to jail so easily. I didn’t hurt anyone around me, so it seemed absolutely crazy,” he added.

Commonly known as Law 52, it sentences drug users from a minimum of one year in prison up to five years in prison and a fine up to 3000 dinar ($1,314) whatever the substance is.

According to the Ministry of Justice, in 2016, there were more than 6,000 people detained in Tunisian jails for drug consumption, which is almost a third of the prison population.

Matmati eventually served an eight-month sentence in Mornaguia prison, south of Tunis, which he described as “a crazy jungle” and was released under a presidential pardon.

The young man, who lives with his mother, said that his arrest was a major ordeal for his family.

'If you want to preserve your children and your principles, you don’t throw them in jail'

- Seif Matmati, former prisoner

His mother, who works as a chef, struggled to find time and money to take a taxi to visit him once a week at Mornagui, which is more than 15 km south of their home in Tunis.

“Once, she was so tired that she started to cry. I told her 'please, don’t come anymore,' but she didn’t want to listen and kept coming,” Matmati recalls.

When he came out of prison, it was very difficult for him to rebuild his life. Music had always been his passion, and he hoped one day to build a successful music career.

But after his arrest, he was not issued an official professional musician’s card, which is requested by clients, such as hotels, to allow musicians to perform and earn concert fees. A copy of of his criminal record is a requirement to issue the musician’s card.

"[Law 52] is not a matter of preserving your children. If you want to preserve your children and your principles, you don’t throw them in jail," Matmati said.

The history of the law

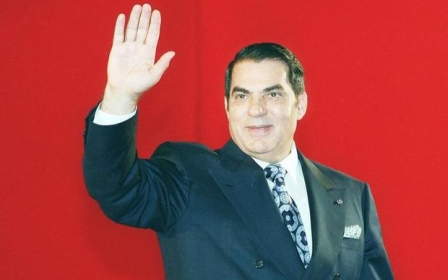

The law was adopted in 1992 under Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali’s dictatorship, after an international drug trafficking case known as “The Couscous Connection,” in which Ben Ali’s brother, Habib, had been involved.

In 1992, Habib Ben Ali was sentenced in France to 10 years in prison for transferring money from heroin and cocaine trafficking between Tunisia, France and the Netherlands.

'The Ministry of Justice introduced a modified version of the bill that reverses some of the potential improvements in the initial draft'

- Human Rights Watch

Before Law 52, prison sentences existed for drug users under Law No 64-47, adopted in 1964. But at the time finding evidence was extremely difficult except in cases where people were caught in the middle of consuming drugs, explained Ghazi Mrabet, a lawyer and founding member of Al Sajin 52 (Prisoner 52), a group of activists fighting for the reform of Law 52.

He added that things changed with the adoption of the new law, which allowed police to order urine tests to prove consumption, and led to many arrests that were based solely on suspicion.

“It is a tool of harassment against the population, especially the youth,” Mrabet said.

Law 52 has also been used to silence dissent. "Some politicians were threatened by [Ben Ali's police] and told some cannabis could be found 'by accident' in their car," said Mrabet, who has defended many of those detained under Law 52.

“Many artists were arrested, mainly rappers, because rap, like everywhere in the world, carries a message of liberation, commitment and a willingness to change," he adds.

Mrabet insists the law is inefficient, citing figures from the Ministry of Justice that indicate a 54 percent recidivism rate for convicted drug users.

According to the Ministry of Health, 13.6 percent of men and 0.4 percent of women consume cannabis in Tunisia.

Amendment of the law

Al Sajin 52 and other organisations like Human Rights Watch are calling for the replacement of the prison sentence for drug users with more lenient alternatives such as fines and community service.

The debate around the drug laws started after the 2011 revolution, when several public figures, such as Slim Amamou, the secretary of state for youth at the time, called for the "repressive law" to be repealed.

These protests and growing media coverage of the arrests pressured President Beji Caid Essebsi to promise to reform Law 52 during his election campaign in 2014 in order to “protect the future of suspects, especially those who are still studying and under the supervision of their families,” he said.

Amended law could be even harsher

A new law on narcotics has been drafted by the government and was sent to the Assembly of the Representatives of the People in December 2015. A year later, discussions began in parliament on 3 January 2017.

But the debate took an unexpected turn, and MPs could yet end up voting on an even more repressive law, according to rights organisations.

'It is a tool of harassment against the population, especially the youth'

"The Ministry of Justice introduced a modified version of the bill that reverses some of the potential improvements in the initial draft," Human Rights Watch said in a statement issued on 19 January.

Furthermore, doping tests would still exist under the amended law with an unexpected novelty: a six-month jail sentence for anyone refusing the test.

Another new measure is the introduction of an “incitement to consumption” offence. Amna Guellali, director of Human Rights Watch Tunisia, told MEE that this measure, if adopted, could undermine freedom of expression and allow attacks on NGOs seeking to ease penalties for consumers or artists who raise the issue of drug consumption in their work.

The draft of the new law is a disappointment to Guellali, who says the law is retrograde and will not help reduce drug abuse in Tunisia. "Prevention is very little dealt within this new bill," she said.

Dr Abdelmajid Zahaf, president of the national office of ATL MST Sida, a Tunisian association focusing on reproductive health and drug issues, explained that there are no medical detox centres in Tunisia today. But at the end of the month his association will open day care centres to help drug addicts in the cities of Gabes and Djerba.

While Hassouna Nasfi, vice chairman of the parliamentary commission on general legislation, told MEE that it will take at least another month before the bill is voted in a plenary session.

'We had rooms crowded with guys. Sometimes we were 125 people in the cell. There were bedbugs, bugs in the cell, rats...'

He added that the commission had not yet decided about the articles relating to sanctions for drug consumers, and that it is difficult to take a final decision because of different points of view between members. During the ongoing debate inside the commission, broadcast by the NGO Al-Bawsala, some MPs said that sanctions were the only way to prevent consumption, while other disagreed.

Bassem Trifi, a lawyer and the vice president of Tunisian League for Human Rights, said that some of the MPs told him that they would “face criticism if they abolish the imprisonment sentence because we live in a conservative society,” he told MEE.

Guellali, who published a report on abuses related to Law 52, said that the detainees live in horrible conditions. "It's hell," she said.

Cycle of violence

Isam Absy has had a very diverse life. After studying civil engineering and becoming a player of the national Tunisian rugby team, the 31-year old is now a security guard in the nightclubs of Gammarth, an upmarket suburb of Tunis, and a rapper in the urban culture collective Gam7.

Sitting in a cafe in Montfleury, a district of Tunis, Absy tells MEE how he was arrested in 2010 following a nightclub brawl.

Although he said he was arrested because of the fight, Absy was eventually forced to take a dope test and convicted to one year in prison in Mornaguia. The conditions in the prison were overcrowded and filthy.

“We had rooms crowded with guys. Sometimes we were 125 people in the cell. There were bedbugs, bugs in the cell, rats also... It's very difficult to live there.”

For Guellali, “these prison sentences do not solve the problem, and can lead to abuse and a cycle of violence that could encourage someone to use more drugs," she said.

Rights lawyers and activists say they will continue to fight against the law.

"I hope that in the coming weeks we will have a new law which respects human dignity, physical integrity, and is modern,” says Mrabet, the lawyer. “When we look at the evolution of the legislation in the biggest democracies in the world, we see that after the repression, they are moving more and more towards lighter sentences for drug users."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.