Jordan's Azraq Syrian refugee camp provides little solace this winter

AZRAQ REFUGEE CAMP, Jordan – “My house was raided, robbed and burned to the ground by regime forces,” said Syrian refugee Ghazi Shehadeh.

“Our village is in northern Syria, but we didn't go to Turkey, we left to go to Jordan because we have the same tribal customs. In Jordan they can understand us better, and we thought that they wouldn’t look at us like strangers,” Shehadeh added.

Exactly three years after that life-altering event, Shehadeh says he is no longer sure he made the right decision. With the UN fast running out of funds and on Monday launching an “unprecedented” $16bn emergency appeal to help the most vulnerable, including many Syrian refugees, and with Jordanian impatience with the more than 600,000 Syrian refugees, there is now little hope that this once proud tribal leader will be able to provide for his family and tribe this winter.

Shehadeh told Middle East Eye that he wasn’t and that the fighting had prevented him from coming to work from his home village of Khabr Fedda, but it didn’t matter. He knew that once he was reported his life and his family would be in grave danger.

With the situation growing increasingly precarious in Syria, Shehadeh spent the next few days and weeks making arrangements for his family to flee to safety in Jordan, along with 80 people from his tribe. He stayed on in his village for a while longer, but once army checkpoints began appearing even there, he too fled south to rejoin his family.

As Shehadeh thinks back to that turbulent time, he shakes his head in disbelief and explains that he still finds it hard to fathom the massive changes that were to come.

"I always thought I would be buried in my ancestral land," he said. “But now I don’t know what the future holds.”

Arrival in Jordan

Arriving in Jordan wasn’t easy but Shehadeh’s family was able to stay with 350 people from their tribe, the Shehadeh. Together, they built a makeshift refugee camp in Kherbet al-Souq, a residential area on the outskirts of Amman where they settled in May 2012 and soon built a school for the refugee children.

They were largely living in tents, Shehadeh recalls, but they had electricity, TVs, refrigerators, and the freedom to work and move freely in Amman. They largely made do with UN vouchers they received and donations from local charities but some residents found employment at a nearby packing factory that helped to generate much-needed income for the camp.

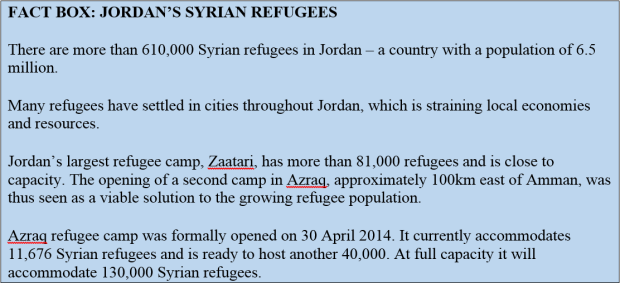

However, after the opening of the Azraq refugee camp on the 30 April 2014 – the UN’s second mass camp for Syrian refugees - the Jordanian government issued an order to close all illegal camps in the country, including the camp that Shehadeh and his family had set up.

Shehadeh said that a large police force arrived at the Amman camp at dawn and ordered the family to pack all their belongings. “Did they expect us to resist?” he said. “The police helped us to pack, but we were not sure where we were going. They processed us in Serhan police station and sent us to Azraq refugee camp.”

The opening of Azraq camp was seen as an opportunity and a new beginning for refugees. However, more than six months after their forced relocation to the camp, many refugees, like Shahadeh, feel isolated and destitute. Home couldn't feel any further away.

Shehadeh feels this pain particularly acutely. Not only is he responsible for his 11 children, but for the 500 members of his tribe that are now living with him in the camp. As their tribal leader, he carries the weight of their wellbeing on his shoulders.

In Khibet al-Souk camp, he explains that he prided himself on having the means to support the tribe in their everyday lives, but in Azraq severe restrictions leave his hands tied.

Poor facilities

Shehadeh and his tribe were expecting the new Azraq camp to be similar in scale and services to the Zaatari refugee camp – the first and largest UN refugee camp in Jordan. The tribe spent a few days there before moving closer to Amman but upon their arrival, they were shocked at the conditions they were presented with.

Azraq camp consisted of a number of shabby corrugated iron shelters that stretch into the distance as far as the eye could see. These shelters were surrounded by desert. There are no electrical appliances or water tanks in the makeshift homes.

With no power or electricity on site, Mahmoud’s tribe were given solar units and lanterns. They could use the units to charge mobile phones, and the lanterns were for restroom visits at night. The units often take all day to charge, and provide light for only three hours. The problems grow particularly acute in winter when shorter daylight hours and poor weather exasperate the problems.

Each family also received sleeping mats, mattresses, blankets, plastic sheets, a kitchen set, a gas canister, a gas stove, a bucket, a 10-litre jerry can and a hygiene kit (toothpaste, toothbrushes, soap bars, detergent, plastic wash basin); quantities can vary depending on the family’s size.

“The gas canister is supposed to last for 45 days, but if it empties before the 45 days are up, families need to wait. One gas canister won’t support a family for a month, especially a big family,” said Abu Fadel another refugee at Azraq, whose dust covered face exaggerated th elines on his aging face.

A system has since emerged whereby families, who are able to leave the camp, sell their gas canister, among other things, while refugees who finish their gas, borrow from others.

Fresh water at the camp is available via community tap units. These taps operate from 7am – noon and from 3pm – 7pm. The water supply is used for drinking, cooking, cleaning and bathing, but the refugees find the supply times inadequate.

“If WC units had their own water tank, then things would be much easier for us,” said Shehadeh.

The UN has launched a string of appeals for funding, but with the number of refugees needing help spiraling and the conflict now about to enter its fifth year, there are limits as to what aid agencies can do.

"I wish we could support everybody and I wish we could give everybody more,” said Amin Awad, director of UNHCR's Middle East and North Africa Bureau. “But the reality is that the population moved and continues to move quickly in 2014 and the funding continues to trickle in slowly."

Some 1.7 million Syrian refugees are now expected to be without crucial food aid this December due to a lack of funds. Those in the two main Jordanian camps, however, will continue to receive some support, something which they appreciate highly despite the difficulty in obtaining produce in the camps.

The only place for refugees to purchase goods is Sameh Market – a private Jordanian grocery chain. Many basic items are not available. “We can only buy what they have. I need a pair of shoes and they are not in stock for now. We have to pay cash for cigarettes – they do not accept our coupons for all items,” said Abu Fadel.

For some refugees, the market is a two-kilometer walk away from their shelter, which can be a difficult walk for the elderly, especially in the harsh Azraq desert climate, where it is either too hot or too cold most of the year.

There are few employment opportunities, and the only jobs available are those provided by camp management. School janitor and labourer positions are the only vacancies, and the wages are 1 Jordanian Dinar ($1.4) per hour. If caught working outside of the camp, refugees can incur a 500 Jordanian Dinar ($US700) fine.

In the beginning, the children did not easily adapt to the conditions on the camp. They were used to watching TV and missed their Jordanian friends in Amman. Jordanians used to come with gifts and candy from time to time. The children also began suffering from an array of ailments such as dry skin and rashes due to the hot, dry and dusty conditions.

However, many of the children – unlike the adults – have largely now adapted. Azraq camp has a playground and the children are going to school, which is something that not all could do before when their parents were pushing them to go to work in Amman to earn.

Some of the refugees are now even trying to grow trees and plants. They would like to make the area greener and grow some of their own produce, as they would be if they were still back at home. “We would like it if the NGOs could provide us with seeds and water, and the chance to raise poultry,” said Umm Muhammed another refugee, in her mid-forties.

Despite the harsh conditions, some families have been able to grow lentils, mallow and rocket.

Trapped by circumstance

Most of the Syrian refugees in Azraq camp want to leave, but in order to do this they have to go through a legal process, known as the “bailout programme”.

This involves a Jordanian citizen, related to them through blood or marriage, to sponsor them. “In some cases refugees pay 1,000 Jordanian Dinar (about $US1,400) to have a Jordanian sponsor them. If the bail is refused, the money is not returned,” said Shehadeh.

In some cases, said Shehadeh, Jordanians ask refugees to marry their daughters or sisters as a favour for bailing them out.

As if to heighten the refugees’ sense of despair and isolation, the camp is encircled with fences that are patrolled by the military. Facilities are guarded by police and private security services – no one comes in or goes out without a permit.

“I loved living in Kherbet al-Souq in Amman. We would like the Jordanians to help us leave. My dream is to go back to Amman,” said Shehadeh. “I wrote a poem, it ends with: ‘I miss Amman and only Amman’s water will stop my thirst.’

“I have been in Azraq camp for six months. I feel like I’m in jail. I’m trying my best to leave, but I want to live legally. My only concern right now is to get out of this swamp.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.