Kuwait makeshift school takes in shunned stateless students

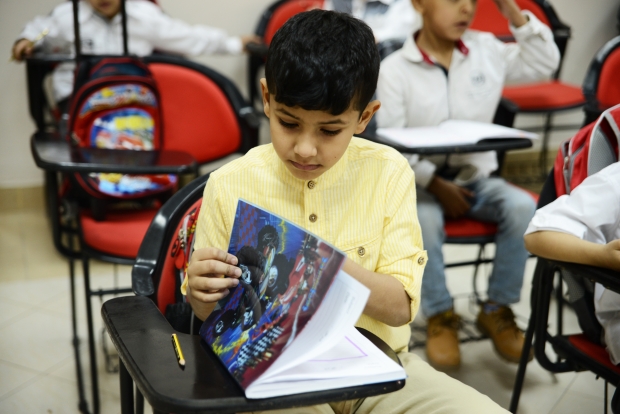

Six-year-old Abdel Rahman is into his sixth week of attending a makeshift school in Kuwait. He is not a refugee, nor did his home country plunge into political unrest that has gripped other nearby nations. The school is neither a tent nor the remains of a shelled building. He, however, is stateless in his own birthplace.

Abdel Rahman, along with 49 other children attending this volunteers-based school, are the youngest generation in a population locally known as “bidoons,” meaning “without” in Arabic, and is short for “without nationality.” Their new teachers, also belonging to the same community, secured two rooms in a building of an independent society to provide classrooms for Abdel Rahman and his colleagues, after they were told they were unwelcome elsewhere.

While the community, which is between 90,000 and 120,000 people in size, says they are the original inhabitants of Kuwait, the government accuses them of forging their statelessness to benefit from generous welfare privileges enjoyed by its 1.2 million citizens. Speaking Kuwaiti and draped in their traditional attire, bidoons perfectly blend into a society that they claim as their own, but are largely pushed to its peripherals by legal obstacles.

They're a "ghost" population, one that is "invisible on the official lists of any national state,” and in the Kuwaiti society, Claire Beaugrand, a researcher at the Institut Français du Proche Orient (Ifpo), said in a study on statelessness and administrative violence that was published in April 2011.

Their plight goes back to the country’s independence in 1961, way before its oil wealth reshaped its skyline and society. It was also then that the state ended a two-year period given to residents within its not-yet-finalised borders to register as citizens. Bidoons allege they're the descendants of nomadic tribes who roamed the north and missed the deadline stated in a nationality law issued in 1959.

“From then on, our description in Kuwaiti official records was gradually reduced, from “bedouins,” to “non-Kuwaitis,” then “with unspecified nationality” to “bears no nationality” and finally “illegal residents,” said a bidoon activist who asked to be referred to as Ahmed Al-Rashed, rather than his real name, for fear of retaliation.

“Katateeb al-bidoon”

The final tag came with a 1986 decision to gradually strip bidoons off all socio-economic rights, including education in public schools, free health services, public sector jobs and the issuance of any official identification documents, including passports, marriage licenses, as well as death and birth certificates. Up until then, the gap between bidoons' lives and those of Kuwaitis’ may have gone unnoticed.

“In 1996, the Kuwaiti government began issuing birth notifications, rather than certificates, for stateless newborns. Today, the government instructed private schools to refuse the admission of children with no birth certificates,” Ahmed al-Khulaifi said.

Khulaifi is the coordinator of the makeshift school, called “Katateeb al-bidoon,” in reference to Katateeb or Kotab, an extinct schooling system which, decades back, provided basic elementary education to children across the Middle East amid the lack or negligence of government institutions. He says over 600 children are harmed by this decision, but the host building has room for only a fraction.

“This initiative cannot be a solution or an alternative, especially when at least 2000 bidoon students across all academic stages, have been warned of expulsion if they provide no birth certificates,” al-Khulaifi said.

But the government says these claims are untrue. Head of the Financial and Administrative Affairs Department at the General Directorate for Private Education, Abdullah Al-Waheeb, said the education of over 15,000 stateless children is being fully financed by the government-run Education Charity Fund, with a capital of over $13m.

“I would never turn away a student who has proper identification, but I simply cannot accept a person without any identification. Those who don’t are not real bidoons. They are children whose parents have nationalities but choose not to list their children as such, to claim statelessness,” al-Waheeb said.

Al-Rashed challenges this argument, saying the government is tightening the issuance of documents that would indicate his community’s rights for a normal life, let alone a proper nationality.

“We all have documents proving that our ancestors were part of the 1965 census, which entitles us to a Kuwaiti citizenship. Many of us also hold proof that their grandfathers were among the bidoons forming 80 percent of the Kuwaiti army up until the eighties. But our children are being increasingly marginalised by stricter procedures,” he said.

“Administrative violence”

This, according to Beaugrand, is how the state practices “administrative violence” against its stateless population, depriving them of rights “through the deprival of identification papers, official forms and certificates. It is used to put pressure on claimants of citizenship so that they drop their claims."

The government also has other solutions for this saga. The Assistant Undersecretary for Citizenship and Passports Affairs in Kuwait's Interior Ministry, Sheik Mazen Jarrah Al-Sabah, was quoted earlier this week as saying that tens of thousands of Bidoons will be receiving applications to receive the citizenship of Comoros.

In May, he said the government’s Central Apparatus for Illegal Residents (CAIR), which was set up in 1996 to handle the matter of bidoons and trace their origins, is working on a deal with an unnamed Arab country for it to offer its citizenship to Kuwait’sstateless in exchange for financial compensations.

Sheikh Mazen referred to a similar deal struck by an Arab nation he did not name. He may have been referring to the neighbouring United Arab Emirates, which is said to have paid millions of dollars to the Comoros for agreeing to give its passports to thousands of its bidoons.

Sheikh Mazen’s comments are not alien to the official stance. In April, pro-government MP Nabil al-Fadhli suggested that stateless people convicted of protesting or jeopardizing national security, must be sent to a camp which the government should build in the desert.

According to the government, out of 93,000-officially-recorded bidoons, the real origins of 67,000 have been traced. Head of CAIR Saleh al-Fadhala displayed graphs in a televised interview last year showing that the majority of those traced were Iraqis, followed by Saudis and Syrians.

A CAIR official was quoted on 11 October saying that 6,256 illegal residents "adjusted their legal status" or resurrected their original passport since 2011 when Kuwait promised benefits and exemptions to those who do.

But when the apparatus' head of public relations, Saleh al-Saeedi, was asked why the 26,000 with no other origins remain stateless, he said “there are a number of requirements that need to be met, such as a clean criminal record.”

It was fear of a tainted criminal record which drove al-Rashed to hide his real identity.

Alternatives

Beaugrand added that such "legal conundrums" with "dead-ends or loose-loose games," are what push bidoons to find "alternative solutions to statelessness and have resorted to emigration citizenship, buying or passport forgery, all tacitly encouraged by the government.”

Mona Kareem, a bidoon activist, had to seek asylum in the US where she was pursuing her PhD after Kuwait rejected to renew a temporary passport she was given for that purpose.

Describing herself as “a stateless in exile,” Mona said she has slim hope of being naturalised. “We are at least three generations into the problem. We do not have hope in this arbitrary and racist state.”

She added that other bidoon activists “hope to politicise the community more and push on different fronts. “We hope for larger political changes in Kuwait and creating coalitions with other groups in Kuwait to enforce full naturalization as the only solution for our struggle.”

An example of such activists is Abdel-Hakim al-Fadhli who has been detained 10 times since 2011, when the community began a series of protests that mostly ended violently. Al-Fadhli, who faces a long list of charges in several bidoon-tied cases, was last released in August after a 30-day detention. In another case, he was also acquitted along with 67 others of participating in an unauthorized protest. He said the case has not been dropped as the authorities appealed the verdict.

Bidoons have grown close to a potent opposition that has increasingly shown sympathy towards their cause. When it held parliamentary majority, the opposition, which largely shares the tribal backgrounds of Kuwait’s stateless population, vied to win the bidoons some rights, even if half-heartedly. So when the opposition boycotted several parliamentary elections and took to the streets in demand of constitutional changes, many bidoons joined.

In November 2014 the UN refugee agency, UNCHR, kicked off a 10-year campaign to end the statelessness of about 10 million people around the world. When CAIR’s al-Saeedi was asked how this affects Kuwait, he said the state has nothing to do with it. “We don’t have any stateless community. Those who claim to be stateless are reducing in number as more and more return to their origins. Prior to the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, there were 220,000 of them in the country and that number shrunk to 117,000 after the liberation. How did they manage to leave if they had no passports?”

His comments will be of little comfort to the children who continue to be "without" and who live as ghosts in their own society. While bureaucracy takes its time to remedy the situation it's a relief, at the very least, that volunteer schools like Katateeb al-bidoon exist to fill the void.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.