Never stop the dance: The trials of Baghdad's ballet school

BAGHDAD - The walls of Al-Ribat theatre in central Baghdad resonate with lively music as a ballet performance gets under way.

Sixteen-year-old Massa Tayseer is dancing with her partner, Maisara Salam, 19, during an April show. Together they glide towards one another in effortless grace.

In a brisk gesture, Salam flings Tayseer in the air. Rotating on her axis, Tayseer's white dress comes apart piece by piece to reveal a much shorter red outfit.

According to her mother Zeina Akram Fayzy, 50, after pictures of the performance with its mid-air outfit loss were shared on social media, a public scandal ensued. "It shocked people," she said, and some people accused Tayseer of offending Islam.

"These people think we live in the land of prophets. But that's not true, Iraq is a land of civilisation,” said Fayzy, who is the only paid ballet teacher at the school.

Following the incident, Tayseer stayed at home for two months because she was afraid to be assaulted on the street.

"I wanted to be a professional dancer, but I don't want to anymore," said Tayseer.

Maisara Salam and Tayseer study at the Baghdad School of Music and Ballet, a mixed national institution where students can immerse themselves in ballets such as Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake as a way of forgetting the chaos and violence in the city.

Located near al-Zawraa Park, the school was founded in 1968 by Iraqi musicians Aziz Ali, Munir Bashir, and husband and wife Fikri and Agnes Bashir.

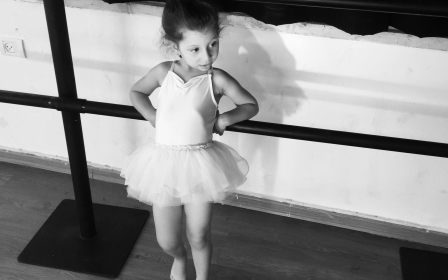

The school offers a full education curriculum, including music and dance, for students aged six to 18 years-old.

According to Ahmed Salem Ghani, director of the school, it is the only one of its kind in Iraq. During the 1970s, Iraq was experiencing an oil boom that gave it a period of prosperity, allowing it to develop as a centre of culture in the Middle East.

Back then, the art of ballet was perceived as being prestigious and modern, so many families appreciated sending their children to the school.

Though there is not an exact figure as to how many students attended initially, Fayzy recalls the school having around 200 students in its first years of existence. The school has not produced international stars, but some dancers such as Maisara Salam have become popular national dancers, Ghani said.

Today Ghani says the school has 586 students, a dramatic increase from only a few years ago, when numbers fell to around 100.

UN sanctions

When Fayzy reminisces about the 1970s, she recalls wearing a colourful dance outfit while dancing alongside her cousin during a public theatrical performance of Scheherazade.

“The school had three female and one male Russian professor. They came from the prestigious Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet,” said Fayzy.

In 1990, the UN Security Council imposed trade sanctions on Iraq that crippled the country’s economy. They were prompted by then-Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait.

The school, which was funded by the Ministry of Culture, experienced its first funding crisis and lost its four former Bolshoi Russian teachers. According to Ghani, they left sometime during the Iraq-Kuwait war.

“The department of ballet was dependent on them,” said Ghani, who has been director of the school since 2012.

The 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq hit the school hard. In April 2003, it was damaged by a bomb and looted, according to Ghani.

Sectarian violence also plagued Iraq following the US invasion, along with a major security void. The school remained open despite these risks, but the number of students decreased sharply.

‘Everything is haram’

“The US-led invasion did not only replace the government, it also changed people. They became less accepting of art,” said Ghani.

The 2006-08 sectarian war brought a more conservative Iraqi society to the fore, with some Iraqis perceiving dance as immoral and haram (forbidden in Islam), according to Ghani.

“When I joined the school in 2004, there were about 100 students in the whole ballet department,” according to Leezan Salam, 22, a volunteer ballet teacher at the school.

“I was nine when I started practising ballet at the school, after the invasion,” said Leezan.

“It was top secret, nobody knew except my immediate family. My father was afraid of kidnappings," Leezan said.

From 2009 to 2013, only three female and two male students took dance classes, Leezan said. Additionally, among the primary school-aged children at the school, 10 attended ballet classes.

In 2013, Salam decided to revive Iraq's passion for ballet and began publishing photos of Baghdad's ballet school on Instagram.

While the page gained popularity among Iraqis and people abroad who were interested in dance and culture, it also received aggressive messages stating the dance was haram and shouldn't be promoted to the Iraqi people.

The US-led invasion did not only replace the government, it also changed people. They became less accepting of art

- Ahmed Salem Ghani, director of Baghdad School of Music and Ballet

“In Iraq, everything is haram in ballet, especially the outfits. On the page, I have to be careful what I post because I can't always show girls' faces. There is no future for ballet in Iraq,” Salam said. Her passion for dance keeps her here.

“In the Iraqi dialect, we have an expression,” said Ghani. “To [imply] that someone has a bad reputation, we say that his/her family dance and play music. And here is a school where we teach music and dance.”

According to Salam, there were some messages requesting that the page be shut down.

Funding crisis

Since 2003, there has been limited funding for the school from the Ministry of Culture, which has always funded the school. The budget today only pays staff salaries.

Apart from this, there is no money for building maintenance, performances or project development. Prior to the US invasion, there was money to fund all of the necessary aspects of running the school. The school does not charge its students but some of the costs of running the school are now borne by the students' families.

“We just have our salaries,” Ghani said. “If students wish to set up a show or any public performance, they should either find private sponsors or pay from their own pockets.”

The restricted budget means only two out of four dance studios are available. The others were abandoned after the floor partially collapsed in one, while dusty musical instruments lie on the floor of the other.

In 2015, $10,000 was donated to the school after the British ambassador to Iraq attended a ballet performance organised by the school. The money was donated by the UK embassy in Baghdad, according to Fayzy.

"The ministry received the funds, unfortunately we didn't see even one dollar,” Fayzy told MEE. Middle East Eye contacted the ministry repeatedly about the missing funds but did not receive a response at time of publication.

I dream of a national ballet group, to spread Iraqi art to the world

- Ahmed Salem Ghani, school director

To cope with the financial crisis, Fayzy often buys shoes and clothing for the students from her own money, purchasing items from Turkey, Jordan, or China. When Saddam Hussein was governing Iraq, the school provided free shoes to the students. Students even wore high-end French ballet shoes made by the company Repetto, Fayzy said.

Fearing a shutdown of the school due to the failure of the Ministry of Culture to allocate finance for maintenance, the director has stopped asking it for any funds. Beginning next year, students will pay a total fee of $200 for the entire six years of primary school education.

“We don't want to charge much, because poor people will lose access to our school,” said Ghani, expressing his concern that the school would just be accessible for the wealthy.

“I dream of a national ballet group, to spread Iraqi art to the world,” said Ghani.

In one of the school's dance halls, Fayzy is teaching a new dance step to a group of four female students. Despite all of the challenges, she refuses to give up.

"I love this school, I cannot leave it," she said.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.