Painting broken streets: A Lebanese art student's quest to revive her city

TRIPOLI, Lebanon - Dressed in a black tracksuit, a rucksack slung over her shoulder, Hayat Chaaban squints up at the Ottoman-era clock-tower above the palm trees and red-roofed houses of Tripoli’s al-Tal Square.

The 19-year-old’s outfit, a familiar look for teenagers in London and New York, stands out in this conservative city on Lebanon’s Mediterranean coast. But then so does her work. A student in the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Lebanese University in El-Koura, she is Tripoli’s only female graffiti artist.

“People are often confused at first. They see a girl out on the street by herself doing graffiti and they double-take. It's quite unusual to see this sort of thing,” said Chabaan.

Raised in Abu Samra, a hilltop neighbourhood of Tripoli with views over the city’s Crusader castle, the young artist is tall, nearly six foot, and practical: long brown hair tied back in a simple ponytail, a sketchbook always close at hand.

“My parents are supportive… some of my neighbours think that I am a bit strange, like a vandal,” she said, a playful smile on her face.

Chaaban, whose work blends traditional Islamic-style calligraphy with Western forms of graffiti, is painting in an increasingly tense environment. Since the outbreak of Syria’s civil war in 2011, Tripoli has witnessed intermittent fighting between two impoverished neighbourhoods: Bab al-Tabbaneh, a mainly Sunni community, sympathetic to the Syrian uprising, and Jabal Mohsen, a hilltop Alawite enclave where support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is strong.

The Lebanese army has arrested hundreds of suspected Islamic State sympathisers whose black flags fly on cars and above buildings in some parts of the city, prompting fears of radicalisation amongst Sunni youth who see the army as subservient to Hezbollah, the Shiite party-militia fighting in support of the Assad government in Syria.

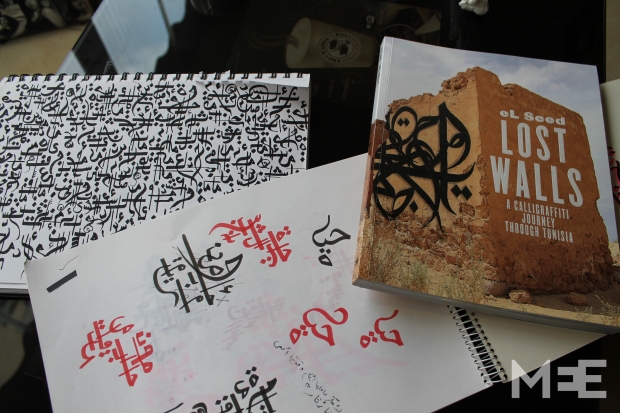

Years before the turmoil of the Arab Spring and the divisions sewn in her country, Chaaban began experimenting with calligraphy at school, scrawling tiny “cheat-sheets” in ancient Arabic script her teachers could not decipher. Later she discovered the work of El Seed and Ali Rafei, Tunisian street artists who combine calligraphy with graffiti to bring colour to impoverished interior towns and direct criticism against political elites.

After years practising at home – in old notepads and on the wall above her bed – Chaaban took her drawing onto the streets last year.

Working on walls down quiet backstreets in Tripoli’s port and among the hustle and bustle of the souks, Chaaban’s work reaches across sectarian divides, working and interacting with members of the city’s majority Sunni and minority Christian populations.

In September, after finishing a piece – a four-tone, 4x2 metre composition that gives thanks to the therapeutic benefits of art (“How cramped is living if it were not for a space for art”) – on a set of stairs close to al-Tal park, Chaaban was approached by the imam of a nearby mosque who led her to a derelict residential building round the block.

“He said he’d pay for the paint if I could transform it,” said Chaaaban.

Covering a ten-foot wall, the swirling, intricate Kufic script appears to almost spill off the concrete.

“After it was completed the sheikh said that every time he walked by the wall he felt a burden had been lifted,” she said.

Months later Chaaban approached Ibrahim Sarouj, a Greek-Orthodox priest and the curator of a library in the city’s old quarter damaged in an arson attack last year by unknown assailants after rumours spread that Sarouj had published an article on the internet critical of Islam and the Prophet.

“She [Hayat] did not ask me for anything. She just explained that she wanted to create a piece to commemorate the library and it’s survival after the fire,” said Ibrahim Sarouj.

A few metres from the library’s old wooden doors, Chaaban’s piece reads: “I faced death and rose up from the ashes.”

Chaaban frequently riffs off the work of Lebanese writers and musicians. One piece on a grubby white wall below an air conditioning unit near her home bears a lyric from a song by famous Lebanese singer Fairuz about the destruction of Lebanon during the 15-year civil war of 1975: “The land is ours, and you are my brother. So why are you killing me?”

Another piece, which twirls up a crumbling set of stairs by a local school, bears a verse by poet Khalil Gibran: “Woe upon a nation where ideologies are many, but religion is absent.”

While some of her work may seem to carry political messages – peace and co-existence are common themes – often, Chaaban says, she wants to “beautify” the city.

The recent violence in Tripoli, a city of 550,000 people, makes it a no-go zone in the eyes of many Lebanese people, a phenomenon that has reinforced the city’s sense of isolation from the rest of the country amidst anger about governmental neglect.

When she’s not drawing, Chaaban volunteers as a guide on tours of Tripoli’s medieval souqs, port and abandoned World Fair Centre built by the renowned Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer in the early 1970s before the civil war, when it was used as a military base by the occupying Syrian army.

“Some people make the effort to see the real face of Tripoli,” says Chaaban. “Others just listen to the media and believe that everyone here is with Islamic State. This was one of the reasons that made me want to do graffiti, to go out on the streets, talk to the people, and try to make some sort of difference.”

“Once when I was out painting this guy passed by and said: ‘Why are you bothering to do this, you're wasting your time, this country isn't worth it.’ A lot of people just want to leave.”

Chaaban says she feels pained by the violence engulfing her city. In January, when al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra carried out a suicide attack on a popular cafe in Jabal Mohsen, she was at home on Twitter.

“I heard the blast,” said Chaaban, shaking her head. “The day before I had been taking part in an event in the Mina. We’d been offering free hugs - you know, to spread love, and peace … then the next day there is this explosion…”

Chaaban says she will continue with her painting, despite the violence.

“Someone has to do it,” said Chaaban flatly. “Often, I don’t think my work is all that. Of course I am happy people are starting to recognise it, but I am doing it because it is what I love. It is also a good outlet.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.