In quiet London suburb, questions remain in killing of Syrian imam

LONDON - Wembley is usually a sleepy west London suburb, known for its stadium and not that much else.

Among the rows and rows of residential homes, a dauntingly large IKEA and a water reservoir where locals sail, sits Greenhill, a tucked away road that is especially green and notably well-off. Like many wealthier pockets in London, it rests close to much poorer areas, but the crime rate here is below average for the city.

When a well-respected imam was gunned down in broad daylight here earlier this week, the killing quickly shook not only the local community, but Londoners at large.

The almost execution-style murder of 48-year-old Abdul Hadi Arwani, who was shot in the chest and left slumped in his car with the window rolled down and nothing taken, quickly made headlines and speculation soon spiralled.

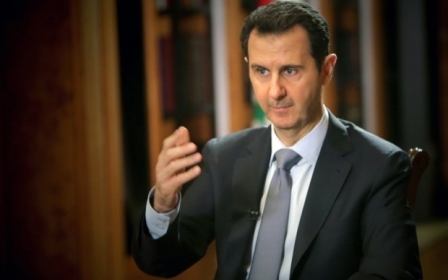

The Daily Mail labelled the killing a "hit squad assassination" and linked it to Arwani’s “fierce” opposition to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. The Mirror followed suit, saying it had confirmed that the case was being treated by counter-terrorism officers.

Early on, the police denied the reports, saying that they were keeping an “open mind” and that normal homicide units would be heading up the case. However, late on Wednesday they, too, announced that counter-terrorism units would be taking over due to their experience with cases involving “international dimensions and an established liaison network abroad”.

Hype or not?

The implications from the media were clear. Sources allegedly close to Arwani told media that the Syrian-born imam had been receiving death threats, with the reports widely describing Arwani as a ferocious critic of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Yet it remains far from certain whether this hype should be believed.

Mahmoud Bondok, a pupil of Arwani’s for more than three years, who described him as a “mentor” and “a father figure”, dismissed the media speculation.

“I have read these reports about the death threats, but he never mentioned, signified or even implied that he was under threat,” Bondok told Middle East Eye. “I was with him this weekend. He was conducting a marriage in Regent’s Park Mosque. He was cheerful, happy, laughing – the same as he always was.

“If he was in danger, then why did he not go to the police? As someone who worked in the community, he had good relations with them. Also, why would you be driving around on your own?!

“I’m sceptical. These rumours are disrespecting the family… What evidence do they have that there is a Syrian hit squad driving around?”

According to a legal source with experience of other counter-terrorism cases, the mere involvement of the Metropolitan Police’s so-called SO15 counter terrorism command should not be seen as a smoking gun.

Cases with any kind of international dimension can be referred to SO15, in part because these units have more resources and can, at times, be less stretched, said the source who was not authorised to speak officially on the matter.

While the family have tried to shy away from the media as much as possible, they, too, have queried the reports.

Arwani’s daughter, 23-year-old Elham, told the London Evening Standard that she had “no idea” what had happened.

“Any Syrian who is free and who knows the truth is against Assad. It’s not going to be because he was against Assad. It must be for another reason… but we can’t think of what.”

Witness to a massacre

Arwani was a Syrian, who suffered terribly at the hands of Assad’s father, Hafez. As a teenager, he witnessed his hometown of Hama razed to the ground. During the “events”, as the February 1982 massacre came to be known in pre-revolution Syria, anywhere between 10,000 to 40,000 people, mainly civilians, in the Syrian town were killed in less than a month.

His father and mother were killed, but the young Arwani managed to escape execution orders, handed down because he was trying to document what happened.

These experiences could have made him hateful, vengeful, violent even, but by almost all accounts, Arwani chose to work his community and help those around him.

And while he spoke out openly about the Assads and the mass killings that have been happening in his home country in the latest brutal four-and-a-bit years, he was far from a household firebrand figure.

Several prominent members of UK’s Syrian community contacted by MEE either said that they had not heard of him, had only heard of his community work through friends and acquaintances, or knew him only in passing. Few knew much about his views or teachings to comment on his death in particular.

Instead, sources close to the imam insist he dedicated himself to mentoring, community outreach and charity work, which in addition to his construction business, occupied the majority of his time.

‘A key symbol’

A particular passion in recent years has been reaching out to youths who might be at risk of radicalisation and tempted to join militant groups.

“Him [Arwani] as a witness to the massacre that happened in the 1980s mean that he was a key symbol,” said Bondok, his student.

“He was known as someone who was advocating for people not to go to Syria. It was very important to have someone who lived through all this and witnessed all this and experiencing first-hand oppression saying that this [flying out and fighting] was not the right way to go about things. This was not good only for the Syrian British community, but for the Syrian revolution,” he added.

“The way you are going about trying to achieve your goals – barbarity and violence – is against Islam. If anyone had any misconceptions, or were listening to people who might be radical, he was there to say no.”

The issue has proven to be a hugely polarising one in Britain: at the start of the year, Kings College London’s International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation estimated that at least 500 to 600 people had left to join militant groups like Islamic State and Nusra Front abroad.

Reverend Nadim Nassar, a Syrian priest living in London who heads up the Awareness Foundation, an organisation aimed at multi-faith understanding, said that while he only crossed Arwani’s path briefly, the imam was a regular at interfaith events.

“We are trying to stop people from importing the conflict from Syria and amplifying it here,” Nassar said.

“I am extremely concerned about radicalisation, not just in the Syrian community but in every community, even the British. This must be the number one priority to stop people from being brainwashed and ideologically groomed to join extremism. It is very concerning.

“We must address these issues and talk to the young people so that they are aware of what is going on.”

In Syria, militants who claim to adhere to this narrow ideology have often turned their weapons not only on opponents, or other religious groups and sects, but also on fellow Sunni Muslims who, for whatever reason, have failed to live up to their narrow interpretation of Islam.

For now, however, it does not appear that this level of animosity has reached British shores.

While the conflict in Syria and, more recently, Yemen has fuelled inter-religious violence in the UK, with a small rise in attacks on UK-based Shiites carried out by other Muslims, there have not been any reported instances of hate crime-type violence within the Sunni community, Fiyaz Mughal, the director of the Tell MAMA Campaign which focused on Islamophobia told MEE.

“There is a lot of very fierce debate and discussion within the community, but no, not violence,” Mughal said.

An Noor Mosque

Some British media has made much of the fact that Arwani was once an imam at the controversial An Noor mosque in Acton, also in West London.

In November 2013, Mohammed Ahmed Mohamed, who was wanted on terrorism charges, managed to evade police at the mosque by donning a burqa and fleeing the country. A few months before that, Mustafa Kamal - the son of Abu Hamza al-Masri who after a lengthy legal battle was extradited to the US in 2012 to stand trial for terrorism-related charges – also reportedly called on believers to take up arms against their enemies at An Noor.

But Arwani left the mosque two years earlier in early 2011 following a dispute. While some have indicated that the spat was over financial issues, others believe it was more ideological.

“I do not wish to comment on the ongoing investigation, but would like to take this opportunity to dispel some of the incorrect information that is appearing,” Arwani’s son Murhaf said in an official family statement issued after the killing.

“He was at one time the imam of the An Noor mosque in Acton until early 2011. At that institution, he was the voice of reason and transparency; A peaceful man in a violent world.”

Hours after his killing, on an unseasonably warm April evening, several hundred people who turned out to mourn Arwani’s passing at a local community centre certainly seemed to remember him in this light.

Cars lined up from one end of the road to the next and veered round a corner. People parked on double yellow lines, and tried to ascend pavements in vain just to get a space. Others simply streamed in on foot across the adjacent rail bridge.

A woman who came with her two teenage daughters said his killing was a tragedy and that she was still in shock.

“He was a very good man. May Allah have mercy on him,” she said.

Another described the sadness she felt when hearing of the crime.

The media was not allowed into the event and few mourners wanted to give their names or talk about what had happened and why in much detail.

The shock amidst the calm

But this did not seem like a community under threat. There was some light security at the event, but only to keep journalists out. Curious residents who walked past and asked what was going on were quick to express their condolences.

“Islamophobia is not that bad. I know areas outside London where people experience it in a bad way, but here in this part of London we have not really had anything that bad happen,” Bondok said.

“Sometimes the EDL (English Defence League) hold protests at the Regent’s Park Mosque (about 10 miles away) but even this does not turn violent. They mainly just scream and shout things and then they walk off.

“I don’t think Islamophobia is at a peak, or at the least at a level where someone would kill you over it,” he added.

According to Metropolitan Police statistics, Islamophobia-related crime in the borough of Brent, where the killing and later the memorial took place, has gone down by 31 percent in the last year.

Conversely, it went up by almost 25 percent across the capital, but these stats are deceptive as only 695 cases were reported across London’s 32 boroughs, which means that wide fluctuations in percentage terms tend to take place in some boroughs even if the figures might move by only a handful of incidents. The true figures are higher and more difficult to document.

But it’s precisely because of the relative calm seen in Wembley and West London that the murder has proven to be so shocking.

“All (he) Arwani wanted to do was help people and fight injustice wherever he saw it,” Bondok said.

“He was never too busy for people. He always had time to sit down, to listen to help. I can’t describe what a positive impact he had on me as an individual and the community. He was always there for everyone who needed it.”

“I only hope that we will keep learning from his example.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.