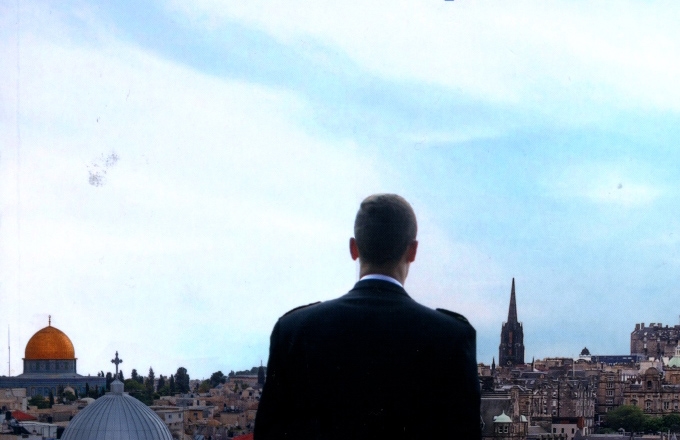

REVIEW: Palestine through the rear-view mirror

Am I a bit naff for wearing a keffiyeh round my neck? It helps warm the soul in the Canadian winter. Are T-shirts depicting Palestine embarrassing? They motivate Philadelphians to dance the dabke.

It’s one thing to be in sympathy with the Palestinian struggle, yet another to be confronted with it by birth. This compilation of over 100 Palestinians’ reflections is testimony of as many individual struggles, each an ongoing “peace process” between longing and belonging. There are myriad metaphors planted amongst the pages, but my favourite is “I see Palestine in my rear-view mirror.”

Just as the Palestinian National Authority rarely considers the opinions of refugees in Lebanon, Jordan and other countries, the Western media haven’t noticed the Diaspora living in their own countries of operation.

Many of the transplanted, who consider themselves Palestinian, grew up to only meet non-family Palestinians when attending university. By this typical path, wanderers faced their own personal intifadas by shaking off a “cultural amnesia,” a condition encouraged by Western societies that are not only un-Arab, they hardly ever consider Arabs.

It’s natural for many within the Diaspora to feel ashamed at their limited, foreign vantage point to Palestinian culture, when they long to aspire to it. But a lifetime of lost sleep, fretting about one’s certified genuineness is what “converted” many secular Ashkenazi Jews to the Zionist’s quasi-faith. When immigrant Israelis wear the uniform, their similarly clad compatriots salute them. Many North American and British Jews dress-up occasionally in this self-delusion, and they save their saluting for special encounters where they might otherwise be judged as disloyal.

The Palestinians don’t have a state machine to weave this culture, so their outward fabric is homemade, wherever their limbs happen to live. Some feel they cannot genuinely identify with the struggle of Palestinian folks actually in the Middle East without taking on victimhood.

Many respondents within the covers of this particular survey declare a dread of being asked, “Where do you come from? “But in London today, I meet people who are keen to volunteer their Palestinian self-identity, which indeed seems the healthier option. The ample Jewish-Zionist presence in America causes one respondent there to feel it’s in bad taste to declare a Palestinian background.

Yet, warm embraces occasionally welcome the Palestinians by virtue of shared liberation, especially in Latin America, where Cubans and former Sandinista Nicaraguans know their history and that of the PLO too.

The fear factor

One New York City-based writer states, “Fear follows me like a rabid dog,” feeling that Palestinian-ness is a kind of stain, one that the majority of Manhattanites will use as an excuse for incarceration or cultural excommunication, removed from the Western cosmopolitan melting pot and flung into society’s compost bin. This unfortunate asks, “Do we inherit fear?”

Of course not, but generations of Jews have incubated this disease, which, like tuberculosis, breeds in close quarters in self-censoring families, neighbourhood ghettos and high-walled West Bank settlements, believing every waking minute that the so-called goyim, that ‘ol conspiracy of “gentiles,” is ready to attack.

One Palestinian-American diarist here feels that Washington and the states it represents are more anti-Palestinian than Israel itself. This cannot be true, but it shows how symptoms of oppression generate when fear goes viral.

Western Palestinians are among the lucky in both situation and choice. They can help their neighbours build moral fitness in striving for the unshackling of the Occupied Territory, or they can go beyond an understandable romantic affliction and even overdose in paranoia, in which case it’s then a hell of a job to try to resuscitate them.

It’s not easy for the community in this book. Their sentences, their stories are as uneven as the South Hebron hills. A single state throughout Palestine would present a somewhat dystopian dawn for both the inhabitants and the currently exiled alike. Like the urban, educated Palestinian people I see, I couldn’t envisage picking olives before high noon, even if my own agrarian ancestors did.

One Stateside contributor daydreams of doing so, but good luck to him. And there are cautions voiced here by those who’ve thought long and hard: an apartheid-expunged Palestine still won’t be a picnic and the past cannot be changed.

Who’d have thought that Sykes and Picot could be a precocious child’s fairy tale “Big Bad Wolf?” Or, that Central American junta gangsters could more successfully inspire Arab racketeers in the West Bank, where the Authority dons different garb and bosses their realm in local dialect?

Palestinians who’ve escaped refugee camps generally find little solace in Arab countries. Regional regimes, including the Israeli enterprise, are frail, if not actually “failed states”. And so the authors of this book hope that an eventual Arab-Jewish conurbation will use history’s wisdom to emerge as fairer, kinder, less petty, and, as Zionist conceit has often put it, “a light unto nations”.

Disappointingly, a gay Palestinian-American makes no reference at all to Israel’s hasbara publicity of marketing abroad, Tel Aviv’s LGBT tolerance as evidence of its democracy.

This book is part social survey, partly an arts reference work in regard to the notable authors and artists the editor was thoughtful enough to include, and part surprise.

One overseas method of mourning a death in the unapproachable Occupied Territories is the strangest, if sweetest process I’ve ever heard: transforming the bereaving person’s entire indoor décor for 40 days and nights in tribute. You might be driven to a tear or two as you follow these routes and diaries that insist that you, please, identify with the outsider, and always check your rear-view mirror.

Being Palestinian is edited by Yasir Suleiman and published by Edinburgh University Press, 2016 (ISBN 9780748634026; 370pp) £16.99. Available on Amazon UK

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.