'The saddest museum director in the world': documenting Syria’s lost antiquities

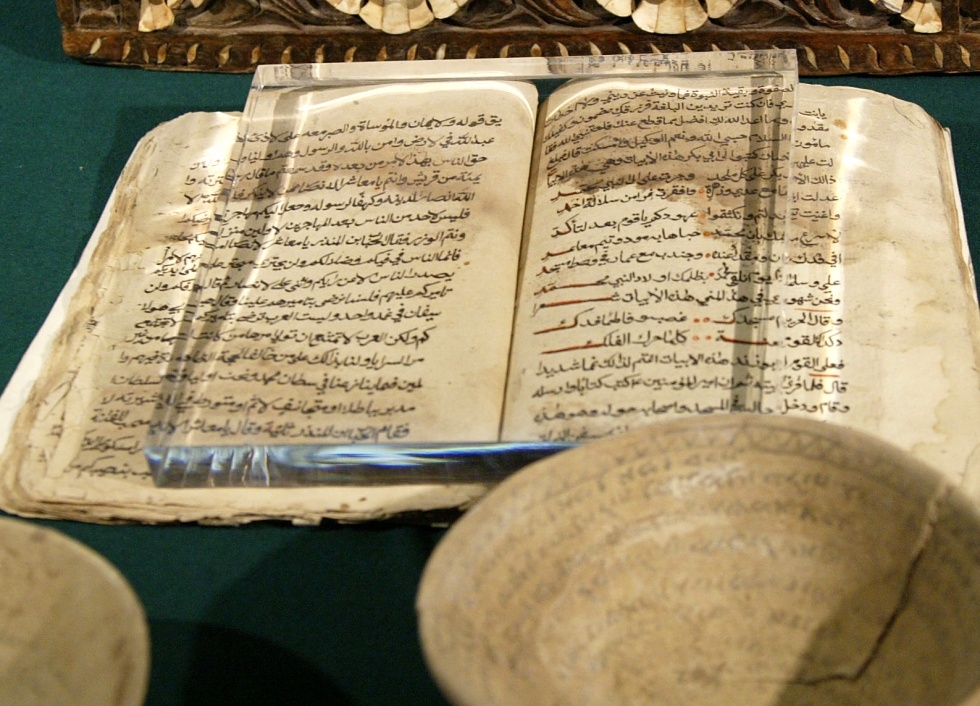

The glass cases stand empty, their precious contents stripped and gone. Priceless artefacts that once graced the National Museum in Damascus from the dozens of cultures and religions that make Syria's heritage unique in the Middle East have vanished, leaving nothing but dusty shelves behind.

Yet, Professor Abdulkarim Maamoun, the General Director of antiquities and museums, counts this as a success and the fruit of one of the largest preservation projects in history. Staff began hiding the museum's treasures more than two years ago, when war first intensified in Syria. The same was done at almost every other museum up and down the country.

For obvious reasons, Professor Maamoun will not say where the museum's treasures have been taken, but he is confident they are secure from almost any threat. The National Archives in central Damascus have also been removed to a secret location.

"We didn't want the Iraq experience here," he said in a laconic reference to the disaster that struck Baghdad in April 2003, when the National Museum in Baghdad was looted and the National Archives torched while American soldiers passively watched.

While some media reports on Syria's crisis have highlighted the looting of archaeological sites, the Professor is a “glass three-quarters full man.” With the optimism and energy that have characterised his leadership of the massive salvage operation, he believes that, given the scale of the war, the preservation of the country's culture is in truth a good-news story. "We have 300,000 objects in 34 major museums throughout the country. We've managed to secure 99 percent of them. I give you a guarantee that after all the drama and sacrifice in Syria, the problem of rescuing our heritage has been solved."

He epitomises the richness of Syrian society himself. While most Syrians resent inquiries about what sect or ethnicity they stem from, Dr. Maamoun beams broadly and without being questioned announces, "My father was Armenian, my mother a Kurd. That's Syria." For many years, he was a professor of archaeology at Damascus University, until 2012, when he was drafted to head the Museum and prepare an action plan to save the country's artefacts.

He saw it as a national emergency to protect the country's very identity and memory.

It resulted in a huge project in which the Syrian army played a large role. "As recently as two weeks ago, a military convoy brought 6000 objects from Homs to safe-keeping in Damascus,” he said. "Various artefacts were transferred from Deir ez Zor by helicopter that were also carrying the bodies of dead soldiers."

The biggest loss was in Raqqa, the headquarters of the militant group IS, where the local museum only managed to preserve some pieces. Over 500 pieces were taken from the Raqqa branch of the Central Bank, where they had been put in strong rooms. A museum of folklore in Deir Atieh was ransacked and a case-load of ancient guns and pistols disappeared.

The museum in Hama lost an Aramaic gold statue from the eighth century.

Even in Raqqa where IS has earned a fearful reputation for barbarity, local staff of the Department of Antiquities continue to function. Helped by tribal and other community leaders, they are trying to negotiate with the militants and remind them that the country's heritage pre-dates and will outlast any political regime, and should be protected rather than destroyed or sold abroad.

The war has damaged a large number of buildings throughout Syria. The eleventh century minaret of the Umayyid mosque in Aleppo has collapsed and part of the central courtyard is in ruins after being struck by a shell. The citadel which the Syrian army occupies is damaged and the ancient cavernous souks were burnt to ash.

But other sites that used to be main destinations for tourists, like the crusader castle of Krak des Chevaliers and the vast Roman oasis city of Palmyra have only suffered slight damage. "They can be restored relatively easily.” The same is true of the convent and monastery at Maaloula," Dr. Maamoun said, with his customary confidence.

He has kept in constant touch with UNESCO in Paris as well as curators at museums across Europe. He presented a plan to UNESCO for the restoration of Krak des Chevaliers in May this year, as soon as the Syrian army succeeded in evicting rebels who had made it a base from which to command the valley below, just like the Crusaders.

He is proud of the work done by local staff who have done as best they can to protect ancient sites. Even now they are negotiating with a group of armed rebels to persuade them to stop occupying the ruined church of San Simeon Stylites near Aleppo. The pillar where the ascetic sat on a platform in meditation for thirty-seven years is at risk if the rebel's weapons stores are hit or explode.

Some ancient monuments have been taken over by homeless people displaced by the conflict.

The biggest problem is keeping thieves away from Syria's archaeological sites. Illegal excavation is taking place on an almost industrial scale at sites like the great columned city of Apamea in the Orontes valley and Ebla, a Ugaritic site in the countryside of Idlib.

Gangs with international criminal links and considerable expertise have sneaked across Syria's borders with Turkey and Lebanon to dig for treasure. As well as at Ebla and Apamea, they are active in the remote eastern regions along the Euphrates. Pillaging was happening before the conflict because of the difficulty in paying enough staff to protect all of Syria's 100,000 sites but the war has produced a massive new wave of criminality. Dr. Maamoun has circulated pictures to Interpol. Some 6,000 objects have been recuperated, including coins, statuettes and pieces of mosaic, thanks to customs and police work.

The sculpture garden of the National Museum in Damascus now contains a small group of Corinthian capitals from Apamea which were discovered on the border being smuggled to Lebanon. Located barely 200 metres from the university, the garden with its cypress, pine and eucalyptus trees is a shady haven for students and couples. A small entrance fee of 75 Syrian pounds (25 pence) or 25 Syrian pounds for students gets you off the traffic-choked streets.

Although the museum itself is closed, the sculpture garden remains open with its large collection of sarcophagi, funeral stones and Roman statues, most of them decapitated by an earlier wave of vandals. The museum director says there is no point in moving them. The sarcophagi are too heavy for looters to remove and the statues are "repetitive," by which Professor Maamoun means there are dozens of similar ones elsewhere.

The museum building has been reinforced with massive steel doors. Special attention has been put to guarding one of its best-known treasures, the Dura-Europos synagogue from the third century AD. Discovered by archaeologists in 1932, its interior walls are covered by astonishing frescoes. They survived for centuries, thanks to well-planned measures of protection in an earlier age of war. The synagogue was filled with sand before the Persians invaded a few years after it was built. Police units are stationed outside the part of the building that houses the synagogue on a round-the-clock basis and the museum has installed a state-of-the-art system of electronic counter-measures to disable any attempt to trigger a car bomb beside it.

Professor Maamoun is in constant touch with his staff around the country who contact him by email with updates about new threats. They have recorded the entire inventory of Syria's museums electronically and maintain a data base of damage and destruction that is regularly updated.

But the work is overwhelming. Professor Maamoun is waiting for a replacement to take over so he can go back to his university job. "I'm very tired. I feel I've been the director here for thirty years. I'm the saddest museum director in the world," he said with a deceptive smile.

"Every day I get reports of theft and damage. It creates a terrible psychological effect on all of our staff. I'm a technocrat, not a politician. But we must find a political solution to this war."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.