Seven men from Deraa, torn apart by war

Four years after the start of protests against the rule of Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian civil war has left more than 200,000 people dead, hundreds of thousands wounded, an unknowable number detained and millions displaced both inside and outside the country.

Towns and villages that people have known for generations are irrevocably changed, and the lives those communities once sustained have been re-routed to refugee camps, migrant ships, militant groups and underground media operations. As told by seven once-ordinary Syrians, four years of war have changed almost everything.

Mustafa: Teacher in exile

Teaching was all Mustafa Abonqth ever wanted to do.

A married father of three, he began teaching 14 years ago in a primary school in the countryside outside the city of Deraa, where many believe the Syrian uprising began in March 2011. Over the years Ostaz (teacher) Mustafa proudly helped hundreds of students graduate to secondary school.

“The greatest part of my job, what brought glory to my family and made me feel loyalty to my career, was seeing my students go on to excel academically at the highest levels of education,” he told Middle East Eye.

“My dreams faded little by little. The war began and with it injustice, murder and destruction; the displacement of families. We were looking for security and justice and humanity, for a place to protect our children from the horrific scenes and preserve their right to life as much as possible and shield them from the abuses that were occurring in Syria.”

This became increasingly difficult, and in early 2013 Mustafa and his wife fled to Jordan and the Zaatari refugee camp. He was devastated.

"My dreams were fading. I felt it was all over for me, living as a refugee at Zaatari, scraping to make a living and trying to build hope for Syria to change course and stop the bloodshed."

At Zaatari, only Jordanians can teach in the camp; Syrian teachers work as assistants. So Mustafa took a job as a teacher’s assistant and worked to get students back into class, and to clear their minds of violence and re-connect to humanity, freedom and dignity.

It has not been easy. According to Mustafa, the work of a teacher at the Zaatari schools doesn’t fit the values and foundations of education.

"They put us in crowded classes, often with more than 70 students. Books and stationery are always late. It’s like they want to destroy a generation that is aspiring for freedom and justice, a generation that is looking for solutions to the problem,” he said. But he won’t let it get the better of him.

“I rearranged my dreams and in order to raise my children in a stable environment and give them the best chance at a future I brought them here to the camp. I’m still trying and I am not giving up."

Zakaria: Wrestling coach to wartime medic

Until four years ago, 40-year-old Zakaria Alvstki’s world was defined by sport. He coached Syria’s national wrestling team and guided his athletes to the highest international levels, seeing many of them compete at Arab and Asian championships.

When the first Deraa protests turned bloody, Zakaria volunteered to drive an ambulance, shuttling wounded demonstrators to ad-hoc field hospitals where they could be treated without incurring the government's wrath.

Zakaria knew immediately that his old life had ended: he had a new purpose. But after 10 days, Syria’s security services intervened.

“They raided my house and arrested me and assaulted me and my family. They detained us at the military security branch, and then took me to Damascus, to Section 248, a military security facility," he said.

The torture began immediately.

“After a few days an officer opened my mouth and forced his shoes in my mouth and started talking on the phone for more than an hour. Afterwards they sent me back to prison, which was unbearable, filled with rats and cockroaches.”

Two months later Zakaria was sent back to Deraa. He immediately returned to work, collaborating with a group of doctors to create Deraa’s first proper field hospital, later devising a secret pathway to evacuate the most grievously wounded people to the Jordanian border. For many people, he is a local hero.

Despite being wounded three times, Zakaria insists his days driving an ambulance through one of the most dangerous places in the world are nowhere near over.

“The regime tried to kill my brother, my cousin and my wife’s brother,” he said. “This makes me more determined to follow my work in the Syrian revolution."

Mutassim: The wounded activist

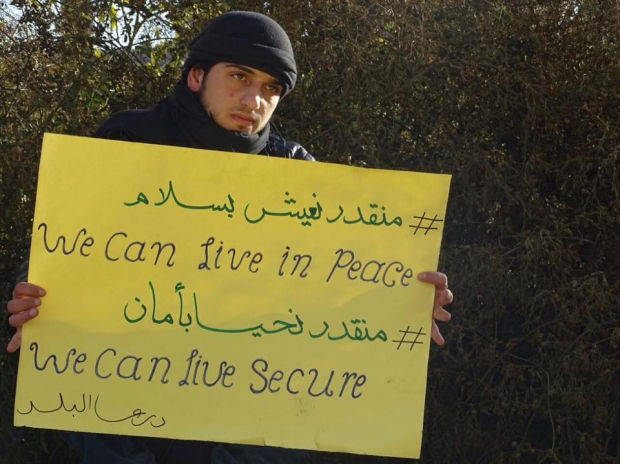

When protests began in his hometown, Mutassim Bedaiwi changed the course of his life completely, leaving his job with a construction company to become a media activist.

He told Middle East Eye he believes that protesting is both a human right and the duty of citizens who see and experience tyranny.

“When the revolution began, many media activists were arrested and tortured. Over the years I have filmed bombings, fighting, explosive barrels and battles between the FSA [Free Syrian Army] and the regime. I hope I can show the world what is happening in Syria,” he said.

Mutassim found paid work doing video reports for a few media groups, but he has also paid a heavy price for his work: 10 months ago he was shot in the abdomen. The damage was extensive and he was rushed to Jordan, where he had six major surgeries.

Now back in Deraa and on still on heavy antibiotics, he has already gone back at work.

Abu Zubair: From the streets of Deraa to al-Qaeda

Abu Zubair is the nom de guerre of a young fighter from Deraa who is now part of Jabhat al-Nusra, or the Nusra Front in English.

Four years ago he was a student at the University of Damascus. He dreamed of a stable life and a family of his own, but when the uprising began he risked the wrath of the security forces and took part in demonstrations in the countryside east of Deraa.

Abu Zubair joined the FSA, but was impressed when the Jabhat al-Nusra militant group, al-Qaeda's Syria branch, began to emerge in early 2012. As the group started to make gains in 2013, Abu Zubair left the FSA and joined Nusra’s ranks.

Abu Elias: From student to media activist

Media activist Abu Elias al-Balad used to have another name, another job, another life entirely.

The Deraa native was a third-year student at the College of Physical Education in Latakia University when his country began to come apart. In April 2011, he was at home visiting his family when police arrested him and put him in prison for several weeks.

After his release he abandoned his degree, fearing for his safety in Latakia, an important centre for the Syrian government and its fearsome shabiha militias loyal to President Bashar al-Assad. He began to take part in demonstrations against the Assads, because of what he saw in the cellars of Syrian intelligence when he was arrested: the widespread torture of detainees.

Abu Elias had always been a networker and a communicator. “Before the war I dreamed of bringing people from all the Syrian governorates together, having meetings through social networking or seminars, connecting people from all over the country,” he said.

The Syrian revolution found a focus for that dream. Abu Elias has worked for nearly four years as a volunteer media activist, taking photos and videos of the conflict and sharing them with opposition media.

Though Abu Elias still dreams of living a normal life, his focus now is the revolution and the fall of the Syrian government, however long that may take.

Dr. Alaa: a doctor in spite of it all

Alaa was a fourth-year student at the College of Medicine in Homs University when the uprisings began. He had hoped to open a clinic in his village after graduating and complete his residency in a hospital, but, as he puts it, “the drums of war had sounded”.

Alaa began volunteering in a field hospital in his hometown of Deraa, patching together increasingly broken bodies with a decreasing number of supplies. When he wasn’t in the field hospital he was studying. But at the beginning of his sixth year of medical school, the security situation became unbearable. It was time to leave.

"I went to Jordan on foot as a refugee with my mother and my little brother. We entered Zaatari camp. I had left behind my studies and my future and I didn’t want to lose them,” he said.

Alaa and his family left Zaatari and travelled to Egypt, where he was able to register at the Faculty of Medicine and complete his studies. He graduated and wanted to complete his licensing exams in Egypt, but high exam fees ($3,500) made it impossible.

Like so many other Syrian doctors, Alaa was unable to practice in an Egyptian hospital. He had come so far, and it was all for nothing.

“I felt despair and depression, like all that I had planned went down the drain,” he said.

Desperate, Alaa looked west – to Europe. He wanted to find a new country where he could immigrate as a doctor and take the follow-up studies required to become a specialist. He approached people-smugglers and paid for the journey across the Mediterranean.

“The trip took many days in the sea and no one knew where we were heading. The boat owners are a gang trading on the lives of the people. Under the threat of force they put us and everything we had on the back of the boat. They said if anyone caused problems they would throw them into the sea. They stole money, mobile devices, anything that was with us,” he told Middle East Eye.

“Miraculously, we finally got to the coast of Italy with the help of Italian coastguard after we had lost hope and were just waiting for death.”

From Italy, Alaa smuggled himself to Hamburg, Germany, where he registered as an asylum-seeker. At long last, he was safe.

Six months later he is learning German and looking for work in hospitals. He has a lot of training ahead of him in order to work as a doctor in Germany, and doesn’t yet know where or how he will complete his studies. But for the first time in a long time, he feels hopeful.

Aziz: An athlete with a gun

Aziz Abazid was born and raised in Deraa al-Balad, one of Deraa's two main districts that houses the old city.

Much like Alvstki, until the uprising began his life centred around sport. He showed promise in track and field and left school early to join the Deraa Athletic Club when he was just 16.

"I dreamed of excelling in the sport that I loved, and I checked off my first dream when I won the championship of the Republic of Sport 400-meter hurdles,” he said.

“I didn’t just want to be the best in Syria: I wanted to compete on the world stage. But my dreams blew away in the wind when the war started, and I lost a lot of friends, relatives and neighbours.”

When the Free Syrian Army rebel group was formed, Aziz joined up and put his sporting knowledge to work as a trainer, eventually becoming a field commander. His brigade is now part of the Southern Front, which is funded by the US-led Friends of Syria and provides Abazid a salary of 15,000 Syrian pounds per month, about $70.

“I still fight to achieve my dreams,” he said. “We’re fighting for freedom and a decent life.”

Aziz has been wounded three times, most recently in early February, when he was hit by shrapnel from a tank shelling a house in Deraa al-Balad. He has already returned to the battlefield.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.