Is Sidi Mohamed Dadach North Africa's Mandela?

LAAYOUNE, Western Sahara – Naman Street is one of the very few tree-lined avenues in Laayoune. The local Sahrawis, however, call it "Dadach" in honour of Sidi Mohamed Dadach, a famous dissident who was received here by thousands after spending 24 years in Moroccan prisons.

At 1,100km south of Rabat, Laayoune is a city of endless rows of drab apartment blocks built by the Spanish 80 years ago to cater to the workers of a big phosphate mine and the port nearby. But the whole of Western Sahara - a territory the size of Britain - changed hands in 1975, when Spain pulled out from its last colony. Today, Rabat claims it as its southernmost province but the United Nations (UN) speaks of a “territory under an unfinished process of decolonisation”.

We're told Dadach is renting a small apartment not far from "his” street but his home is constantly watched by the Moroccan police, and so are the handful of journalists who set foot in this overlooked corner of the Maghreb.

Medir Plandolit, a Catalan correspondent who spent four years in Rabat, told MEE about an alleged media blackout enforced by Morocco: “Western Sahara is a no-go area for reporters. In the unlikely case one gets permission to visit the area, they will only allow you to join a tour arranged by the Moroccan authorities, so interviews with Dadach, or any other Sahrawi pro-independence leader or human rights advocate, are not included in the programme.”

The reporter also spoke about the “red lines” Morocco-based reporters have to cope with:

"There are three: religion, the king and territoriality, that is, the Western Sahara issue," underlined Plandolit, who left the country in 2010 “due to mounting pressure” from the Moroccan authorities.

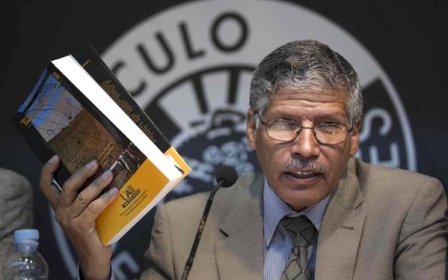

Middle East Eye got rare access to Dadach at an undisclosed location in the outskirts of Laayoune. A green camouflage shirt visible under his traditional loose garbs gave the first hint to the story he was about to tell.

Born in 1957 in Guelta, a remote village on the Mauritanian border, Dadach recalls getting his Spanish ID in 1972, and points to a document that lost its value in 1975 when the Spaniards withdrew.

“Co-existence between us and them was not perfect but we worked together and there was some mutual respect," he added. Dadach, however, did not hesitate to join the ranks of the Polisario Front when the Sahrawi pro-independence organisation was founded in 1973.

Born in the heat of the Spanish occupation, the Polisario would later wage a long and exhausting war against Morocco, until a truce between both sides was signed in 1991. Based in the refugee camps in Tindouf, in western Algeria, the Polisario is the authority today recognised by the UN as the legitimate representative of the Saharawi people.

Rabat controls almost the whole territory including the entire Atlantic coast, yet there's a tiny desert strip of land under Sahrawi control, the so called “liberated territories”.

"In 1975 we were told that we were at war but we hardly had any weapons to fight with. Morocco had tanks and fighter jets so we could not face them until we received trucks loaded with weapons from Libya, Yugoslavia and other eastern European countries," recalled this man, who started his dissident career as a child-soldier.

Dadach was captured in 1976 by the same Moroccan army he was forced to join two years later to avoid the death penalty. His plan was to defect and join the ranks of the Polisario. His only attempt, he said, was unsuccessful:

“I had an accident in the vehicle I was travelling in but I ended up in prison again, this time with a broken arm.”

The young rebel was sentenced to death in 1980 and he would spend 14 years on Moroccan death row. He remembers every each and single day as triumph: "I spent all those years incommunicado in a 2x1.5-metre cell full of cockroaches coming out from the toilet hole. I could only sleep from midday until four in the afternoon because executions were always conducted at night and I was always awake at every noise of the main gate, every single footstep of the guards…"

In 1994, Dadach's death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. He managed to tell his relatives and friends that he was still alive. Meanwhile, he made contact with fellow prisoners linked to banned Communist organisations.

"The majority of them were Moroccans but deeply sympathetic to the Saharawi cause," claimed Dadach. Among others, he made friends with Abraham Serfaty, a Communist militant of Jewish origin who spent 17 years in prison and eight in exile for his political ideas before becoming advisor to King Mohamed VI on his return to the country in 1999.

Dadach's case finally attracted international attention, something which led to a visit by the Red Cross and Amnesty International in 1997 and 1998 respectively. After both meetings, his imprisonment conditions were improved until he was finally released in November 2001.

"They woke me up at night so I thought I was going to be executed. I didn't know what was going on,” remembered the activist. “They took me to the warden and he told me: "'Dadach, you're leaving today'. I remember I left at three in the morning."

The first contact with the reality of the 21st century was the cell phone somebody handed him. "I had never seen one before and it simply didn't stop ringing," he said. During the reception in "his” street in Laayoune, Dadach was asked to say a few words to the crowd. He was brief and straight to the point: "I just got out of jail but my claim for independence for the Saharawi people remains as fresh as the day I was made prisoner."

The mass gathering reached its climax with a pro-independence demonstration in the streets of Laayoune immediately afterwards. Dadach proudly claims he has taken part in all those protests held in Laayoune ever since, including that of Gdeim Izzik, the protest camp set up outside Laayoune for almost a month in 2010. Many western analysts argue that the so-called “Arab Spring” started here, rather than in Tunisia.

A frozen conflict in the Sahara

Despite several phone calls and emails, the Moroccan authorities did not respond to MEE's requests for comments on the circumstances of Sidi Mohamed Dadach's imprisonment.

Some have drawn comparisons between Nelson Madela and Dadach, in part because Dadach is said to be the political prisoner who had spend the longest time in prison in Africa second only to Mandela. Not all find this comparison convincing however. Bernabé López Garcia, professor of Islamic History at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM), labels the long confinement of this Sahrawi as "an unfair suffering," but he is reluctant to make a comparison between Dadach and Nelson Mandela.

"The outcome of Mandela's struggle is clear to everyone, but that of Dadach, as well as other Sahrawi activists, is still yet to be seen. Other dissidents in Morocco such as Abraham Serfaty have also been paralleled with Mandela, but one cannot establish any similarity other than their lengthy time in prison," the senior Spanish scholar told MEE.

Whereas South Africa got rid of the apartheid system in the early 90s, Western Sahara's conflict still remains unlocked 40 years after the occupation. Aminatou Haidar, the best-known Sahrawi human rights activist worldwide, told MEE that France and Spain, the former colonial powers, are “highly responsible” for the suffering of her people.

"Spain has completely dissociated itself from its former colony while France - Morocco's close ally and veto country at the UN Security Council - keeps hampering any resolution toward referendum or an improvement of human rights,” stressed the activist. So far, she added, neither Madrid nor Paris have shown real willingness to solve the conflict.

For the time being, the United Nations Mission for a Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) has been unable to enforce the main task it was created for in 1991, that is, organising and ensuring a free and fair referendum.

Meanwhile, international organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have consistently denounced human rights abuses suffered by the Sahrawi people in the hands of Morocco over decades.

Dadach obviously knows about it first hand, but that has not prevented him from rebuilding his life since his release. Other than a key figure in the Sahrawi pro-independence movement, he's also the proud father of five: three boys and two girls.

“I would like you to come home and meet them but I'm afraid that's not possible, at least not this time,” he added, just before leaving the ochre apartment block in the outskirts of Laayoune.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.