'They tell lies': Israel's 'museum of coexistence' erases Palestinian history

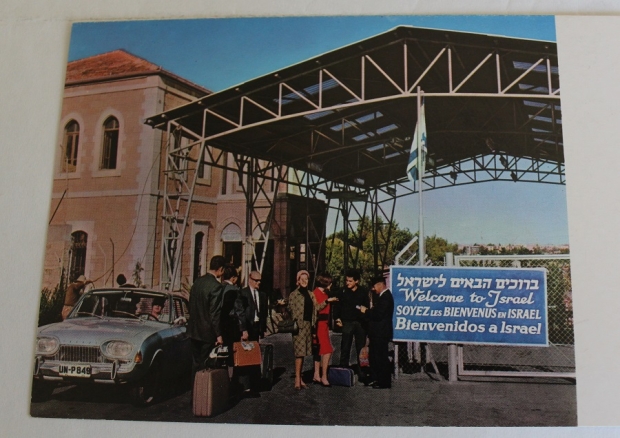

JERUSALEM - The Mandelbaum Gate stood between the new State of Israel and Jordan from 1948 to 1967. Serving as a crossing point between the divided city, it had all the trappings of a traditional border: paperwork checks, barbed-wire fences and welcome signs. In many of the pictures, a three-storey house can be seen peaking out from across the gate, with large Corinthian arches decorating the façade and an Israeli flag flying in front of it.

'The story of the house really symbolises the story of Palestine,'

- Haifa Baramki

But the house in the background, known as the "Tourjeman Post," remains, transformed into a contemporary, socio-political art museum. Named the Museum on the Seam, in a nod to its unique placement in Jerusalem’s historical landscape, it "presents art as a language with no boundaries in order to raise controversial social issues for public discussion".

“Halt! Frontier Ahead” one sign reads, rendered in blocky letters next to a Hebrew translation. In another, vibrant with the bright hues of 1960s Kodachrome, a sign reads “Welcome to Israel,” and happy travellers, dressed in their finest clothes, pose beside a chain link fence. In some, Jordanian soldiers, dressed in traditional keffiyehs, stand guard next to travel posters, urging tourists to visit “Petra....the mysterious!”

The building which houses the museum was built in 1932 by Palestinian architect Andoni Baramki. A single line on the museum’s introductory website and a sign on the ground floor says this, and then launches into the building’s military history.

The museum’s curator, Raphie Etgar, founded the museum in 1999. Today, his office sits on the roof of the museum, which provides an expansive view of the once-divided city. Below, the Jerusalem light rail runs every few minutes, its cars decorated with Israeli flags, and a logo celebrating 50 years of unification.

'Half truths are not enough, you really have to tell the whole story'

- Haifa Baramki

Etgar, a curator with little time for discussion of his museum’s programme, refused to comment on the history of the building which houses his institution. “Everything you need to know is on the website,” he said, a book titled Coexistence sitting in front of him on his desk.

A hidden history

Haifa Baramki, whose father-in-law designed and constructed the house in the early 1930s, remembers the rich history of the family home, before they were expelled during the Nakba in 1948.

“This was built and owned by Andoni Baramki,” Baramki told Middle East Eye, emphasising the word "owned". Unpacking a large file filled with pictures, literature, and newspaper stories about the house, she shook her head. “It was owned by Baramki. The museum is not going to claim it now, but this is a fact. Half-truths are not enough, you really have to tell the whole story.”

‘It was owned by Barkami’

- Haifa Baramki

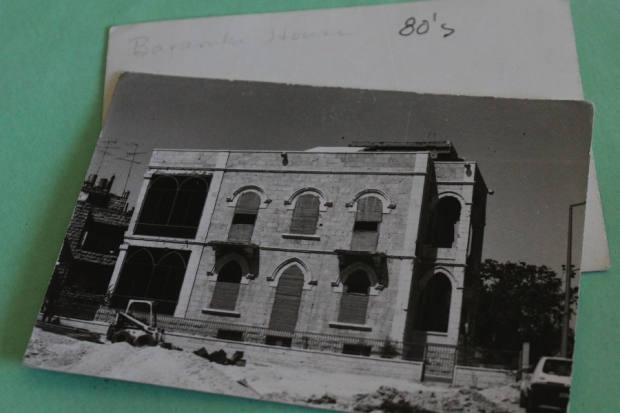

“He was educated in Greece, and went to the University of Athens,” Baramki said, pointing out the large arches of the façade in an old photograph from the 1980s. “These are the Corinthian arches, and this is the Greek influence, but he only built in the red stone, which came from a quarry in the south of Palestine,” Baramki said. “If you look around Jerusalem, in areas like Baka, you will see his stamps, and he always used this stone.”

From family home to military post

After Andoni completed construction on the home in 1934, his family and various tenants lived in the house until 1948. But like so many other Palestinian families, the Baramkis were forced out of Jerusalem during the Nakba (Catastrophe) when the state of Israel was created. The house, formidable in size and structure, was located just beyond the barbed wire that came to separate East and West Jerusalem, on the Israeli side.

Soon after the border was established, the Israeli military transformed the Baramki home into the Tourjeman Post, a military post complete with gun turrets and lookout positions.

‘We see your father coming to look at this house as though he has lost a lover’

- Taxi drivers

Baramki’s husband, Gabi, a former president of Birzeit University, kept track of the family home’s status throughout his life. Though he passed away in 2012, Baramki still keeps his thick file of paperwork, deed documents, and ephemera in their Ramallah home.

In 1967, when the Mandelbaum Gate was taken down and the Tourjeman Post was abandoned by the Israeli military, her father-in-law was eager to return. However, under the Absentees’ Property Law enacted by Israel in 1950, the Baramki family home had been passed to the Israeli Custodian of Absentee Property. No matter how many times he appealed for return, he was denied.

“At the point that Jerusalem was open, from 1967, he started going and visiting the house,” Baramki said.

“Up to when he died in 1971, he went daily from Ramallah to Jerusalem to just stand in front of the house, and just see it. And even the taxi drivers that brought him would come to my husband and say ‘Gabi, we see your father coming to look at this house as though he has lost a lover.’ He was broken-hearted.”

'It's more like alter-existence'

The Baramki home, then controlled by the Jerusalem municipality, became a museum in 1983. Supported by the Jerusalem Foundation, its shell-blasted, crumbling façade served as an entryway for the Tourjeman Post Museum.

Organised by then-mayor Teddy Kollek and supported by German donor Georg von Holtzbrinck, the museum featured a permanent exhibition entitled, Jerusalem – A Divided City Reunited.

'The Museum’s attitude towards Jerusalem Arabs reflects the dilemma of a united city with a divided population'

- Abraham Rabinovich, author of "The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter that Transformed the Middle East

The problematic nature of the building’s identity, especially in light of the Tourjeman Post Museum’s celebration of reunification, did not go unnoticed in the early '80s.

On 11 May, 1983, Abraham Rabinovich, author of The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter that Transformed the Middle East, wrote an article for a special Jerusalem Day supplement saying that, “The Museum’s attitude towards Jerusalem Arabs reflects the dilemma of a united city with a divided population. A municipal museum presumably serves the entire population, but here the story is clearly told from the Israeli point of view, although references to Arabs are dignified and respectful.”

He added at the bottom of his article: “Museum authorities please note: the failure to provide English translations of the documents on view gives the impression that these are of interest to the Israeli visitor only.”

Today, the Museum on the Seam tells the short history of its building in three languages: Arabic, Hebrew and English. Their programming has expanded to encompass all manners of social realities, in order to create dialogues that encourage social responsibility.

But throughout their current exhibition, a survey of religious and secular Jewish art, explanations are only offered in Hebrew and English. In a museum that claims to examine seam lines in their local and universal contexts, the omission of Arabic, both on the museum labels and on the website, does not necessarily align with their mission statement.

'The Israeli government is intent not only on erasing the Palestinians’ presence, but also on erasing their culture'

- Maryvelma O’Neil, director of ARCH

Maryvelma O’Neil is the director of the Alliance to Restore Cultural Heritage of Jerusalem (ARCH). She views the museum’s programming and omission of the building’s Palestinian history as symptomatic of a larger trend in Israeli cultural institutions.

“The Israeli government is intent not only on erasing the Palestinians’ presence, but also on erasing their culture through deliberate acts of memoricide, a practice that the Romans called damnatio memoriae,” O’Neil told Middle East Eye, referring to a term used by Israeli historian Ilan Pape to discuss the act of Israel obliterating remains of the Palestinian people from the land they took in 1948.

“Whenever Israeli organisations host programmes, Palestinians are not invited or deliberately avoid association so there is no ‘co-existence’. It is more like alter-existence," she added.

The museum’s exhibitions cover an impressive range of topics, from the relationship between private homes and national homes, to archives of repression, to loneliness in the urban environment. But by not engaging directly with the history embedded within the museum’s own walls, there is an inherent problem in the way it functions.

“[It’s] too much kumbaya that seeks to strum as loudly and insistently as possible to drown out the indigenous oud music of Palestinian culture,” O’Neil said.

Examining an old black and white poster from the 1980s, depicting the Tourjeman Post Museum, Baramki meditated on the re-appropriation of her family’s property.

“They called it the Museum for Coexistence, the Museum for Reconciliation, the Museum on the Seam - the museum for I don’t know what,” she said. “The story of the house really symbolises the story of Palestine, of what happened to the Palestinians, and it’s continuing. They tell lies, and they have distorted the history.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.