Turkey's on-screen villain 'Turgay Baba' is real-life hero

ISTANBUL, Turkey – Turkish actor Turgay Tanulku’s life was changed forever in 1970. As a politically active 18-year-old, he was arrested and jailed for his beliefs. Rather than become embittered by injustices in his country, it marked the beginning of a journey that has transformed him into a real-life hero.

Turkey experienced raging street battles between leftist and rightist groups throughout the '60s, '70s and '80s that ended in a military coup. During those years, Turkish police stations and prisons were notorious for torturing detainees.

Although he doesn't like to talk about it much, a seven-year prison term left Tanulku a changed man in that he learned to empathise with his fellow beings, regardless of who they were or what they had done, and he developed a love for theatre and acting.

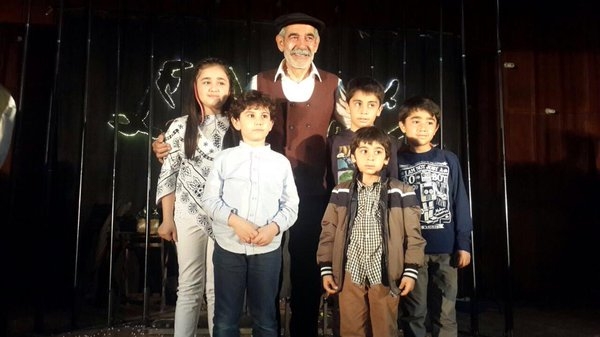

Now 63, Tanulku often plays bad guys on screen and is perhaps best known for his role as a crime boss in the hit regional television series, The Valley of the Wolves. His onscreen persona is a far cry from the caring man who has opened his doors to children in need for the last 35 years.

Tanulku's empathy, and the fact that because of the torture he endured in prison, he was unable to father children, led him to open his doors to youngsters in need after his release in 1977.

“During those years, I realised that it was the innocent children of inmates who suffered the real punishment, and I decided to do whatever I could to be of some support to them,” Tanulku told Middle East Eye. “So when a few of my fellow inmates asked me if I would watch out for their kids upon my release, I didn’t hesitate to agree.”

From that moment, he never stopped adopting or accepting the guardianship of children whose incarcerated parents asked for help. Gradually he even began to get requests from prison guards who for whatever reason - mostly financial - were unable to properly care for their children.

“I remember the crestfallen look on my wife’s face when she learned we wouldn’t be able to have children. I promised her then that we would have many children, one way or another,” Tanulku said, smiling. “I think I have kept my promise.”

His outreach didn't stop there. He also opened his doors to kids living rough on the streets, mostly substance abusers seeking escape from difficult situations.

23 children... at the moment

Tanulku, known as Turgay Baba (father) to his wards and their beleaguered parents, can now count his children in the hundreds. At the moment, he has 23 youngsters that he provides for in some manner.

Through his earnings as an actor, his extended family’s financial needs are met, while like-minded friends help take care of the kids in five rented houses in various Turkish cities. There are also secret benefactors.

Even if these gestures are simple acts of kindness, Tanulku insists that all benefactors remain anonymous because he believes that in a country as polarised as Turkey, some people could aim to exploit the situation. He doesn't want the children to suffer in any way or to be used as public-relations tools.

“I remember one famous personality approached me and expressed an interest in assisting financially. I told that person about having to be anonymous and the person agreed. The next day that person was on TV throwing names around and saying how they were financially helping kids in need,” he said.

Overcoming the worst of fears

In 1981, four years after his release from prison, Tanulku was back again, but not as an inmate. He volunteered to organise theatre and courses for prisoners.

Walking in through the prison gates was difficult for him. "I had to overcome all the fear and loathing that had developed over my seven years of imprisonment. I had to come face-to-face with my torturers or near replicas of them,” Tanulku said. “Thinking of the plight of my less-fortunate brothers helped me to stay strong and not relent.”

Ever since, Tanulku has volunteered his services and organised theatrical performances - sometimes including inmates - hundreds of times in prisons across the country.

The one rule he has set for himself is to never ask why the inmates are serving time.

“You have to look at them simply as human beings without being judgmental. If I knew why they were doing time, perhaps I wouldn’t involve them in plays. But that isn’t the point. Of course in some instances you wonder, but it's generally better not to know.”

Tanulku says theatre helped transport him to another world and maintain his sanity during his own incarceration and he wants others to have the same opportunity.

“You close your eyes and you are gone,” he said. “Plus, if inmates are left alone and idle, the risk of them getting involved in unsavoury things is higher. Involving them in projects helps them learn something new and helps them develop self-respect.”

Halil Saka, a social worker at Istanbul’s Silivri prison complex, agrees. He said that social projects of all sorts can play an important role in the rehabilitation of inmates. He also points out that it is quite natural for the priorities of social workers and those of officials to differ in high-security prisons.

“I always remind everyone, inmates and prison guards, that all of us are potential inmates, but of course it is prison, and the first and only priority of officials is security,” Saka told MEE. “Nevertheless, we arrange various seminars and social activities for the inmates to the maximum extent possible.”

Tanulku’s theatre initiative also falls within the scope of such social responsibility activities carried out with backing from the Justice Ministry and prison boards.

Turkey has a current prison population of about 180,000.

‘The last of the birds’

The latest drama being performed by Tanulku and his friends is a play called The Last of the Birds. The 158th performance of this play was recently delivered before an audience of about 200 inmates at the Silivri prison complex.

The play highlights what inmates feel most deprived of and the almost immeasurable level of despair they face. It was was well-received, with Tanulku and the performers receiving a rapturous round of applause and a standing ovation from the inmates.

“The inmates will not buy into it and participate unless they trust you. It is important to show them that you understand what they are going through,” Tanulku said.

Two of the performers, Volkan Korhan (25) and Resul Dundar (28), are Tanulku’s children.

Dundar is completing a master’s degree in cinematography and like Tanulku, he wants to do whatever is in his power to humanise inmates in the eyes of society.

“I was very touched by what Turgay Baba is doing. I wanted to be part of it. Not just theatre, but I also want to set up photography exhibitions and make a movie to show that inmates are just as human as the rest of us,” Dundar told MEE. “I put myself in their place and it makes me want to help them.”

A father’s pride

With so many children to call his own, Tanulku’s wards have taken up diverse professions, but the one who makes him the most visibly emotional is Sultan, one of his daughters, who qualified as a prosecutor four months ago.

“Sultan’s career choice and all our journeys and roles that led to it are incredible, and I am immensely proud of her,” Tanulku said, blinking back tears.

Sultan was visiting her imprisoned father when she met a prosecutor who was kind to her. That was when she decided to become one, Tanulku said.

Another instance Tanulku recalls, with a chuckle, is the time a handyman was called to their house to do a few repairs.

“I gave Sultan some money to pay the handyman. She came back and said: ‘He says tell Turgay Baba his money is not valid with me. He doesn’t remember me, but I will never forget what he did for my child when I was in prison.’”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.