Two decades of pain: Lebanese village still reeling from Israeli 'massacre'

QANA, Lebanon - Atop a hill overlooking the historical land of Galilee, in a town where Jesus is believed to have transformed water into wine, the skeleton of an Israeli tank stands intact.

Behind it a church lies in ruins, its interior completely gutted. The floor is still carpeted with remnants of broken glass, burnt pieces of cloth, rusty bits of artillery and wooden poles that once supported the roof.

A simple and linear monument facing the adjacent road bears the names of the 106 people who lost their lives in the span of five minutes 20 years ago when Israel bombed the headquarters of the Fijian battalion of the UN interposition forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL) – an act that has gone down in history as the Qana massacre.

At that time, more than 800 civilians were in the compound, seeking refuge from Israel’s operation “Grapes of Wrath” - a 16-day attack on south Lebanon with the declared intent of crushing Hezbollah.

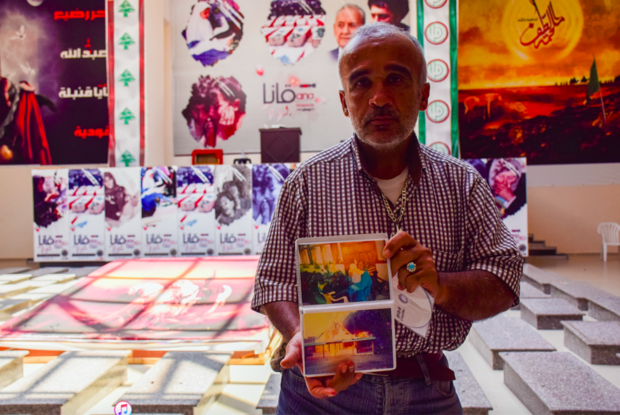

Jamil (Jimmy) Salame, a 49-year-old father of three, was inside when the bombs started to fall that bloody April.

Limping heavily on one leg, Salame trots towards visitors as they cross the threshold of the memorial site. As the self-proclaimed gatekeeper, he spends every day of the week recounting visitors the same story he has been telling for two decades.

“Every day on the radio we got news of a new village being shelled by Israel, so many people from the area came to Qana to find shelter in the UN compound,” says Salame, who at the time was working as a handyman for the Fijian battalion.

“It was little before 2pm on a Thursday when we heard the shelling getting closer and closer. We all knew Israel would bomb Qana, but we thought our families would be safe inside the UN compound.”

They were proved terribly wrong.

“All I could see was fire and blood. I saw corpses and injured people – some were missing a leg, an arm, an eye,” he says.

In a pouch strapped around his waist, he still keeps proof of what he witnessed, freely showing grizzly pictures he managed to take on the day of the massacre. Salame says that, despite the shock and the pain caused by the shrapnel that ripped through his arm and leg, he knew he had to record what he saw so that one day the world would know what happened here.

As he flicks through the photo book, the images of bodies torn apart or lying lifeless on the blood-soaked ground starkly illustrate the scale of destruction.

“I still see it before my eyes as if it was happening now,” says Salame. “These images have been in my mind every day for 20 years.”

For him, the UN compound had been a second home. His father abandoned the family when he was a toddler, leaving his mother to provide for four children.

He started working as a handyman for the Fijian battalion at the age of 20 to help his family and quickly developed a tight relationship with the international troops who were first mandated in 1978 to monitor the peace between Israel and Lebanon after Israel invaded following a string of raids by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO).

“I learnt English with them, word after word, and they gave me food to bring home,” he says. “They were like my brothers.”

While he does not know how to read or write English or Arabic, Salame has other tools to keep the memory alive.

“I want to tell everyone what happened here because no one talks about it in other countries,” he says. “They say the shelling lasted 16 days, but to us each day felt like a year. I want everyone to know what Israel did, it shall not be forgotten.”

A village destroyed

Israeli officers claim the shelling was caused by a computer error while attempting to target Hezbollah fighters firing in the proximity of the Fijian base.

The technical survey conducted by the UN, however, concluded that it was “unlikely that the shelling of the United Nations compound was the result of gross technical and/or procedural errors.”

Contrary to repeated denials by Israeli officials, a video confirmed the presence of two helicopters and a remotely piloted vehicle above the area of Qana before the attack, seemingly contradicting Israel’s claim that it was unaware of the presence of civilians in the UN compound.

Much to the fury of residents, both the UN investigation report and the video were at first concealed due to intense political pressure from the United States and Israel. However, they were quickly leaked to The Independent by UNIFIL, sparking widespread outrage.

In 2005, a group of survivors filed a lawsuit in an American court against former Israeli Army chief of staff Moshe Yaalon. The United States District Court dismissed the complaint, claiming that Yaalon was entitled to immunity under the Foreign Sovereignty Immunity Act.

The misery of losing 100 lives in a close-knitted community, combined with frustrations over their inability to get international justice, means that twenty years on wounds have been slow to heal and many of the victim’s relatives still cannot find closure.

The trauma was further compounded when 10 years ago, Israel again launched a war against Hezbollah in 2006, devastating much of south Lebanon. Qana was hit once more and 28 people were killed in a single airstrike on 30 July 2006.

“Everyone here does their bit,” says Imad Sbeity, a Qana resident. “Some clean the memorial, others drive the tourist bus, and so on.”

Salame has stayed on as a tour guide on a volunteer basis for decades, living off visitor’s tips and says that no matter how hard times get, he will keep doing his job. Salame feels it is important to keep telling people about the horrors that happened in the village which remains a tourist destination for the faithful who believe Jesus performed his first miracle here.

“He has three children and gets no salary from the municipality, all he does is on a voluntary basis,” Sbeity told MEE.

Many of the survivors – some of whom lost more than one relative - continue to congregate at the cemetery every week to mourn the dead.

But few lost as much as Sadallah Balhas. The Israeli attack in 1996 killed 31 members of his family and also cost him his eye. Before passing away a few years ago, he was well-known for wearing a pendant with pictures of his deceased relatives and acting as a key driving force behind the lawsuit against Yaalon.

“That is not something anyone can forget nor, I dare say, would want to forget,” says Nicholas Blanford, a journalist who witnessed the immediate aftermath of the shelling and who wrote a recent piece to mark its 20th anniversary.

“I think there will always be a bond among those who experienced the massacre, whether the civilian survivors, the UNIFIL troops or the journalists.”

What I saw that day “was the most harrowing and traumatic experience I have had. I found it hard to walk into butchers' shops because the smell of blood and fresh meat would take me straight back to Qana,” he adds.

The memory was so harrowing that Blanford says that for years he would watch a video of the massacre on its anniversary.

“It was not the images that upset me - the images have always been there in my mind. It was the sounds - the screams, the wailing, that would move me most and take me back to Qana,” he says.

As Salame locks the door to the memorial behind him for the day, he says that he will never forget the tragedies that befell his small but ancient village.

“We cannot change what happened,” says Salame. “The only thing left to do is prevent our stories from going unheard.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.