Why Yemen remains on a dangerous trajectory

SANA'A - Abdulla Bin Hader gave up his weapon. The 39-year-old from the tribal and rural province of Marib sold his AK-47 in 2011, after joining protesters here in the capital calling for the downfall of then long-time leader Ali Abdullah Saleh, and bought a computer instead. Now he is asking others to do the same.

“We never imagined we would have to protest again,” he said. “Armed militias brought us back to square one.”

Though Hader admits his family still keeps a gun in their home, he took to the streets this week with a cadre of 300 to demand that bands of armed Houthis and their supporters hand over their weapons to the state, remove themselves from government institutions they seized and prepare the nation for an anticipated referendum on Yemen’s new constitution, which is still being drafted.

The militias have been a permanent fixture on Sana’a’s streets since 21 September when a group known as the Houthis, or Ansarallah, and their supporters, overran the capital. They set up checkpoints where state security retreated and battled government troops and militias loyal to Islah, a powerful Islamist party, with heavy weapons in clashes which killed close to 300 people.

The Houthis, who originate from Yemen’s north where they began their Zaidi Shiite movement, are political opponents of Islah who joined a unity government after Saleh was toppled in 2012. The Houthis' push into Sana’a after several other military victories against Islah strongholds earlier in the year left Islah weakened, and was seen as a victory for the Houthis against the status quo.

Hader counts himself as an independent revolutionary who took part in the mass protests in 2011 that also fought against a 33-year status-quo. At that time, with Yemen's pro-democracy uprising in full swing, the Houthis and Islah were united against Saleh.

Despite fears from independents that parties, namely Islah, were using the movement against Saleh for political gain, the ex-leader was eventually pressured to sign over his presidency to then vice-president Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi in exchange for legal immunity.

As Saleh stepped down, Yemenis – many begrudgingly – signed up to a peaceful transition that included national reconciliatory talks led by Hadi aimed at uniting a fractured nation. At that point, revolutionary calls for a civil state still seemed possible. Today, many are less certain.

“We still have cards to play,” said 39-year-old demonstrator Abdo Al-Fageeh. “It’s not game over yet.” But even he could not hide his disillusionment with a state that has appeared to disintegrate over night, pushing Yemen’s transition further to the margins.

Al-Fageeh acknowledged that his rally cry seems like a lone voice when compared to the thousands that united behind the Houthis before they swept into the captial. This tactic - peaceful protests followed by a swift military advance - has seen the Houthis gain control of western parts of the country. “No one’s willing to resist [the Houthis],” Al-Fageeh said.

As Hader and his anti-militia troupe called for an end of weapons proliferation, the Houthis were in the final stages of securing the takeover of several other Yemeni provinces and cities, including the strategic port of Hodeida, where state security forces again melted away as Houthis set up their checkpoints throughout the area. The Houthis have moved south into the areas of Ibb and Ta’iz, tightening their grip on the country.

On Wednesday and Thursday, the Houthis battled to establish their presence in parts of the eastern Al-Bayda’ province where Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) is known to flourish.

While some cheered the Houthis for challenging al-Qaeda, others remain deeply disillusioned with President Hadi, chiding him for letting the state fall into the hands of an armed rebel group.

Sectarian violence

On the other side of the anti-militia camp in Sana’a on Tuesday, thousands of Houthi supporters gathered for a funeral procession for victims killed in a suicide bombing last week targeting a Houthi gathering. Ansar Al-Sharia, a subsidiary of AQAP, claimed responsibility for the attack after the terror group warned of a backlash if the Houthis gained power.

The gruesome aftermath of the attack which killed almost 50 people and injured over 100 others, including many children, raised fears of Syria-style sectarianism in the country, a fate from which Yemen has been largely immune.

Ali Alseraji, a 31-year-old engineer and Houthi supporter, attended the funeral and dismissed worries that he or his fellow supporters could be the next targets.

“We don’t care. We have our aims and goals and that is to fight corruption,” he said.

The Houthis have appointed themselves guardians of a UN-backed peace deal major that political parties signed with the Houthis after they took Sana’a. In the deal, they agreed to form a new government to steer the nation until national elections take place. As a part of the deal, a new prime minister, Khaled Bahah, was appointed this week.

“We will monitor [Bahah] closely. We are ready to change him at any moment if he doesn’t do his job,” said Alseraji.

Alseraji also said the very street militias that the demonstrators were protesting against, or as he refers to them, popular committees, are what will keep the population safe from potential terror attacks.

But several say the opposite may play out. Analysts argue that as long as the Houthis continue to undermine the government’s authority, Yemen will remain on a dangerous trajectory.

A young member of the Socialist party also blames politicians for leaving the public largely in the dark about recent events. Mutte Dammaj says President Hadi failed to engage the public, offering only explanations of an international “conspiracy” for the fall of Sana’a.

“People will not believe political explanations and resort to sectarian rhetoric [if they are not informed about what really happened],” he added.

Political outlet

As just one of the countries in the region plotting its course post-regime fall, Yemenis are quick to point out countries whose paths they do not want to follow. This is why, Hazza Al-Hemuari, a member of the Islah party, said the Houthis need to be very careful not to politically marginalise his faction.

While some prominent members of Islah have been accused of supporting AQAP, Al-Hemuari says Sunni youth need a legitimate political outlet or risk the lure of joining extremist groups. As an example, he cites the way the Islamic State has recruited disenfranchised Sunnis to their cause.

“Islah provides a balance for youth who might otherwise turn to al-Qaeda,” he said.

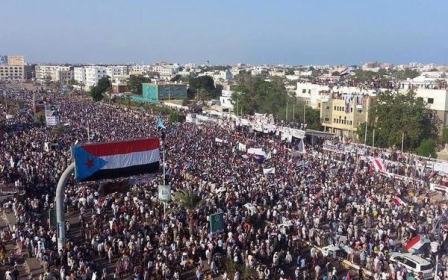

Meanwhile, in Yemen’s south, hundreds of thousands peacefully took to the street on Tuesday, to mark the date 51 years ago when the former state of South Yemen overthrew its British colonial power. While southerners celebrate this date every year, calls for a southern secession have grown louder. This year, the altered political landscape in the north, gave an unprecedented clout to the calls for separation.

Thousands of pro-seperatist protesters remained in sit-in camps on Thursday, saying they wanted send a message to the international community that southern sovereignty was the only way forward.

“There are groups in the south that are serious about separation and those that are not,” said Mohammed Al-Sadi, a member of the group known as Hirak, also known as the Southern Movement. The group is broadly labeled as secessionist but includes many that still view Yemen’s unity as viable.

“What has changed is the situation in Sana’a. People lost faith in the NDC [where Hiraki leaders agreed to a unified Yemeni state] when they saw no one in Sana’a is now accountable,” said Al-Sadi. “But if separation happens now, it’s emotional, not logical.” He argued that the south has no practical plan for reestablishing it as a separate state.

“What would we do if the south fails?” he asked.

But while the demonstrators back in Sana’a said they would continue to raise their voices against the carrying of weapons outside of state forces, they too proceed with uncertainty.

“We don’t know how this will end,” said 36-year-old Samer Alalesi. “People now think weapons are the way to take control. Don’t be surprised if this happens in the south.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.