Words of war: The world of a young female journalist in Benghazi

How one young woman’s experiences in post-revolutionary Benghazi transformed her from a day-dreaming teenager into a journalist reporting from one of Libya’s most dangerous cities

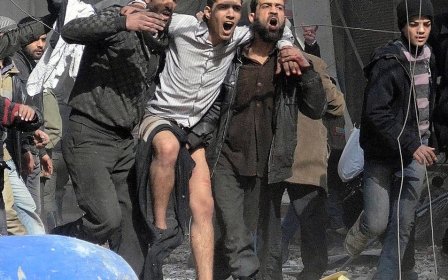

Benghazi has become a war zone more dangerous and destructive than anywhere in the 2011 revolution

Published date: 16 February 2015 11:54 GMT

|

Last update: 9 years 9 months ago

TRIPOLI, Libya - The whole of Libya’s eastern city of Benghazi is in darkness. Tracer fire and explosions sporadically illuminate the night sky. A 21-year old woman stands at the highest point in her family’s garden on the phone, giving a journalist in Tripoli the details of that day’s fighting.

Unable to reach any officials for confirmation, *Mariam Ahmed's analysis is based on where the fighting is taking place and the type of weapons being used. Eight months living in a city that has become a war zone more dangerous and destructive than anywhere in the 2011 revolution, she has learned to identify every type of gunfire, missile and explosion by sound alone.

This is the third consecutive night of power cuts in a city torn apart by months of heavy clashes between the Libyan National Army (LNA) - operating under the internationally-recognised government based in the east of the country - and armed groups including Ansar Al-Sharia, now loosely-affiliated with the Tripoli-based government that was established after a movement called Libya Dawn took control of the capital last summer.

The situation in Benghazi has been brought close to a humanitarian crisis. Medical facilities are chronically overstretched - hospitals try to treat the wounded with just 10 percent of staff, according to one surgeon. Prices even for necessities have soared, there is rarely internet access and Libya’s two mobile networks have not worked properly for weeks.

Mariam charges her mobile phone in her father’s car for these late-night attempts to pick up a signal and relay accurate information to the outside world about the realities on the ground in Benghazi.

“That’s all,” she says, before hanging up. “Oh, the sky is full of stars tonight. It looks so lovely, but you can never capture it on camera.” To a soundtrack of heavy weaponry, she still looks at the sky in awe.

“When the revolution started, I was just a normal girl,” Mariam says. After the liberation of Benghazi she started her English degree and, looking for part-time work, found a new English language newspaper which needed writers. “I didn’t know what it meant to be a reporter, but I went to a party celebrating the anniversary of NATO intervention and that was my first story,” she says.

After writing a few more pieces on everyday life in Benghazi, the assassinations which came to define the city from mid-2012 began. Many hundred military and security personnel, activists and journalists have been individually assassinated in a relentless series of often daily attacks.

“When they started killing the police and army, I just couldn’t stop working,” Mariam says. “I saw people dying, giving their bodies and souls for Libya and I felt a duty to my country to report, so people could see what was really happening.”

Living in a deeply conservative society and rarely able to visit crime scenes, she found ways to work from home, building a network of contacts via telephone and social media.

“I stopped putting my name on articles when the killings increased. Anyone who went on TV and spoke about the assassinations would be killed,” she explains. “But I only did this because, here, they also come after your family.”

Since the revolution ended, press freedom NGO Reports Without Borders (RWB) has registered seven murders, 37 abductions and over 100 acts of harassment targeting journalists in Libya. Several in Benghazi have been killed with many more fleeing the country after being threatened. Mariam ignored threats sent on Facebook calling her kafir (infidel) and ordering her to stop writing.

“I feel like death is following me everywhere,” she says matter-of-factly. “I expect that I am going to die at any time. I have lost a lot of friends and I feel as though my time is coming.” Her gentle voice belies a tough interior, hardened by loss and hardship. Friends, fellow journalists and political activists, killed in Benghazi include 18-year old activist and blogger Tawfiq Ben Suad and lawyer and women’s rights activist Salwa Bugaighis.

Another lost friend was American journalist Steven Sotloff, killed in Syria by ISIS in September 2014, who she met in Benghazi after the revolution. “He was not like a normal journalist, he loved Libya and really believed in the revolution,” she says. “And he knew so much about Islam.” After Steven went to Syria he stopped replying to her messages, which left her vacillating between concern and annoyance, as she felt abandoned by her friend. She contacted the family and was asked by Steven’s father not to enquire further. “I knew something was wrong, that they were hiding something, but I couldn’t do anything.”

When she found out about Steven’s death, she was devastated. “I was so upset when I saw pictures of him in Syria. He had lost so much weight and I know how much he loved food,” she says, unable to hold back the tears. “It broke me. I couldn’t stop crying.”

For a young woman who has reported on so many deaths in three years, she retains an extraordinary humanity. Facts relayed about killings are often supplemented with heart-breaking details - a young son left sitting in an empty car after his father was killed, blood-spattered shoes outside a mosque hit by a stray missile.

“All the good people are gone, and we don’t know where this will finish,” she says sadly, mentioning the death of a neighbour. “When anyone leaves my house, I feel like I’m never going to see them again.”

By the end of 2013, with assassinations commonplace and the authorities seemingly unable to bring anyone to justice for the killings, many Benghazi residents felt desperate. The government’s inability to secure the city led to it being increasingly controlled by Ansar Al-Sharia, declared a terrorist organisation by the US and the UN.

In May 2014, retired General Khalifa Haftar launched an offensive called Operation Dignity on Ansar Al-Sharia and other armed groups in the city, so-named because it was designed to end the assassinations in Benghazi that, he said, had stripped residents of their dignity. The operation was later absorbed into the LNA.

Mariam’s reporting took a new turn, as she found herself living in a war-zone. International media had renewed interest in Benghazi and she started working with more foreign news outlets, reporting from what became the heart of the conflict.

With the university closed and, unable to leave the house for weeks on end, she mastered English through the words of war, trying to give exact details to foreign reporters. Instead of textbooks and grammar formulas, her education came by translating military terms, and describing weaponry and injuries.

When senior commanders found out how old she was, they would always try to help, she explains. “Even when I asked stupid questions, they were patient with me, especially when they saw I respected the difference between on-record and off-record.” As Haftar became an increasingly important and controversial figure, she arranged interviews for international media, as well as interviewing him herself, over the phone.

“It was difficult in the beginning interviewing such people but not now. I have done so many,” she explains. “Journalism has completely changed me and I have a strong personality now.”

It has also changed her outlook on life. “I look at the world from a different perspective now. My mind was like a normal girl’s before, but reporting has made me a woman,” she says. “But it has killed small things inside me and, when I talk with my friends, I feel much older and more serious.”

Her degree remains unfinished and no one knows when the university will reopen. “Benghazi University needs millions to rebuild. My facility has been destroyed,” she explains. But Mariam says she has learned so much more from her unexpected career as a journalist, something which has also given her independence - a hard-earned rarity for a young Libyan woman. “I take no money from my father at all. I am working and financially independent,” she says proudly.

Despite fleeting moments of hopelessness, when describing the rubble her city has become or the daily deaths from fighting, Mariam is known amongst colleagues for her resilience and optimism. “During heavy clashes, I sometimes say I want to leave, but in my heart I don’t want to. I love my country and working as a journalist has made me love it more,” she explains.

“Sometimes I ask why I couldn’t have been born somewhere else, where there is security and where I could study,” Mariam says. “But then I think about rebuilding my country in the future. There has been a lot of bloodshed and many have died, but our future prosperity will be more precious and valuable because of this human cost.”

*NOTE: Mariam Ahmed is a pseudonym, used because of difficulties and security threats faced by journalists currently working in Benghazi.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.