800 dead from hunger, illness inside besieged Aleppo prison

At least 800 prisoners, trapped in a Syrian jail for more than a year as army officers inside and surrounding rebels battle, have died as a result of starvation and illness, according to a former prisoner, a current prisoner and an organization documenting the prison’s conditions.

An estimated 2,400 prisoners – including women and children – remain in the Central Aleppo Prison in which guards intentionally withhold food and medicine, according to the prisoners and a spokesman for the Damascus-based Violations Documentation Center.

“Death surrounds us,” Mohammed, a current prisoner who says he bought a phone from a guard and asked only to be identified by his first name, told the MEE. “And fear, and hunger, and cold, and illness and darkness and our unknown fate.”

Though independently unverifiable, Mohammed’s claims are supported by a Violations Documentation Center report on the prison scheduled to be released this week and a UN official who asked to remain anonymous.

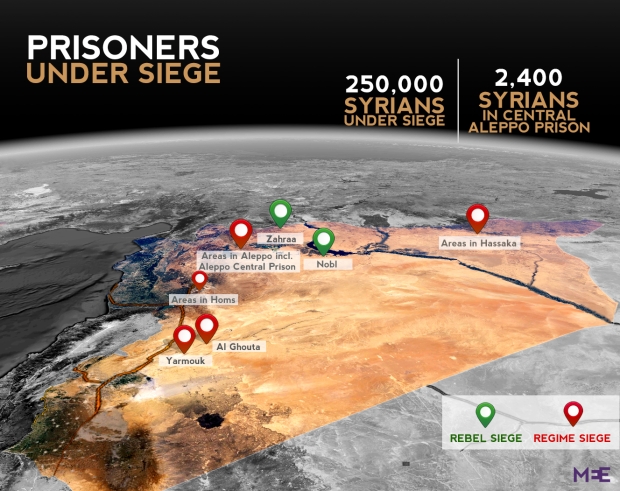

An estimated 250,000 Syrians currently live under siege and have been cut off from regular supplies of electricity, food and medicine for more than a year and a half, according to an Amnesty International report released in March.

Government forces have imposed a majority of the sieges, but there are at least two villages west of Aleppo which are under rebel sieges, according the report.

Despite a UN Security Council resolution in February which called for the immediate cessation of the sieges, Secretary General Ban Ki Moon, in a report to the council on 23 March, said no new ceasefires had been brokered since the vote and there had been breaches of existing ceasefires.

Reports emerging from the prison paint a dark picture of an increasingly stalemated battle as the country enters a fourth year of civil war.

Since April 2013, Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham rebels have surrounded the cement complex, trying to free prisoners, many of whom entered before the civil war began and have since finished their sentences, according to Maher Isbar, a former prisoner.

During the past year of siege, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) has delivered food and medicine, according to Vivian Tou’meh, SARC Communications Coordinator.

But Isbar and Mohammed, the current prisoner, say that police and army officers have regularly withheld the Red Crescent’s supplies from the prisoners. Some prisoners, however, have been able to obtain food, medicine and sundries by having their families pay the families of prison guards, he said. A kilo of rice is 15,000 Syrian liras ($103) and a kilo of sugar is 20,000 liras ($138).

In addition to starvation, Mohammed said, frostbite and illnesses including tuberculosis and more minor ailments, like diarrhea and gastroenteritis, have killed many of the 800 prisoners who were left to die in rooms by themselves before burial in the prison’s eastern courtyard, now a make-shift graveyard.

Starvation, said Neil Sammonds, Amnesty International’s Researcher on Syria, Lebanon and Jordan, has become a deliberate policy and weapon of war used by the Syrian government.

“It’s probably the crudest and cheapest form of attacking a population completely indiscriminately,” Sammonds said.

Isbar, the former prisoner, said he is now acting as a de factor mediator to end the siege. A month ago, he said, communications with United Nations Special Envoy Lakhdar Brahimi’s office, who Isbar said were helping to facilitate negotiations between the government and rebels, “went cold”.

After 18 March, when the Syrian army took back Yabroud, a Lebanese border town through which rebel forces had been smuggling arms, Isbar said he learned that the government no longer sought to negotiate.

Yet according to both Isbar and Mohammed, the 300 police and army officers inside the prison, many of whom are from villages in northern Syria where rebels has wrested control over the past week, want to end the crisis. More than half, they said, are injured.

Farhan Haq, a Deputy Spokesman for the UN Security-General who said he was in touch with Brahimi’s team, said the Joint Special Representative has played a role in mediating ceasefires locally in Syria, but was not involved in the Aleppo prison negotiations.

The Syrian government did not respond to a request for comment.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported on 1 April that 150,000 Syrians have been killed since the conflict began in 2011.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.