The ‘absurd’ war: How Riyadh sacked the Yemeni fighters defending its border

TAIZ, Yemen - When Ali returned home to his village in Taiz's al-Shimayateen district, he dare not tell his friends and family what he had been doing during the past few months.

Like many Yemenis, war-time poverty had forced the unemployed 29-year-old cook, who had been working in Sanaa, to make tough choices to survive.

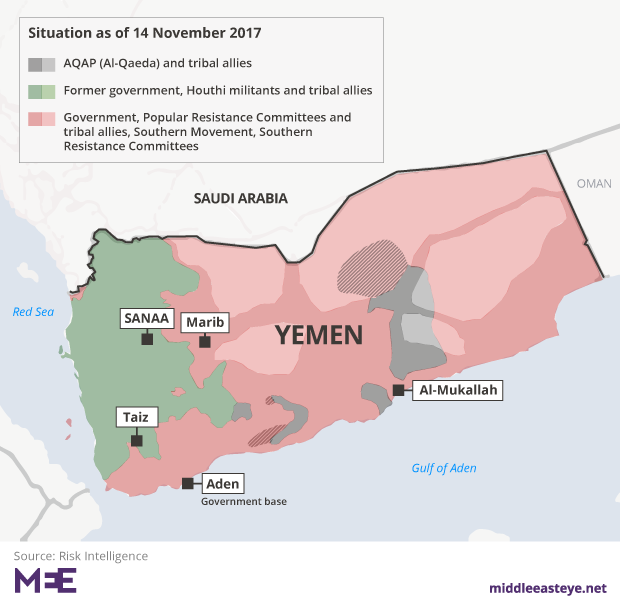

In Ali's case it was to become a mercenary, to fight on behalf of Saudi Arabia, which has bombed Yemen since early 2015, to defend the kingdom’s borders from the Houthi rebels. Meanwhile, the Saudi forces themselves stayed stationed several kilometres behind the frontlines.

"I was not happy to fight for the Saudis, since I believe that most fighters in Saudi are not happy to fight,” says Ali, who like others in this report did not give his name amid fears for his safety. “It is the poverty that forced us to do this.”But then Saudi began sacking many of its Yemeni fighters.

The lure of war

The attraction of fighting for Saudi was clear to the unemployed Yemenis, from teachers and civil servants to delivery drivers and builders, who signed up. Yemen's average wage is $66 per month but fighting on behalf of Riyadh could see a fighter paid anything from SR2,500 to SR3,000 ($800) per month.

Most of the fighters came from poorer communities in Taiz, Marib and southern provinces such as Abyan, Lahij, Shabwa and Hadhramout. A small number of fighters, according to those returning to Yemen, were Salafis exiled by the Houthis from Saada in 2014, who often preached to their fellow fighters by way of encouragement. The majority, however, were fighting for money.

But then, according to Ali, the fighting died down during the late summer and autumn, and was certainly not as fierce as when he first arrived.

"I was fighting in the Habash Mountains, which is part of Najran,” Ali says, “and during the last three months, we did not attack the Houthis and they did not attack us."

I hardly get food but I will not return to Saudi, even if it means I will die. We need the war to end and to start rebuilding our country

- Tawfeeq, former Saudi mercenary

He adds that the Yemeni leadership, employed by the Saudis, told Ali and others in August not to retaliate against the Houthis, even if they were attacked. The rebels also stopped advancing. "In the mountains, no side can advance easily, as five snipers at the top of a hill can stop hundreds of troops, so it is an absurd war."

He says that even if the Saudi-backed fighters took over one or two mountains, there are still dozens to take in the al-Boque area in Saada's Ketaf district.

Walid, a 26-year-old Arabic languages graduate stationed in Najran in south-west Saudi Arabia, went to the battlefield in April. After a few weeks training, he was paid around SR10,000 ($800 per month) for four months' fighting.

Walid says his wage was enough for him to help his family while saving half for himself. But then the Saudis stopped paying the Yemenis who had joined up in 2017 and who, according to Walid, made up more than half the fighting force.He estimates that each battalion contained more than a thousand fighters, that there are dozens of such units and that a quarter of that number could do the task.

Fearful of losing their income, hundreds of Yemenis, including Walid, marched in peaceful unarmed protest towards the Saudi military camps, where the Saudis and fighters from other Arab nationalities arrested them.

Saudi officers then told them that they were no longer needed, paid each fighter SR1,500 and sent them back to Marib where they had trained months earlier.

Talk of Houthi-Saudi deal

But many mercenaries have found it tough to adjust once they are back in Yemen.

Tawfeeq, who Middle East Eye spoke to in August, shot himself in the leg to escape the front. He is now home and unemployed. While many people criticised him for signing up, others sympathised and he is now reliant on the generosity of philanthropists to survive.

"Earlier this year, the Saudis were preventing fighters from returning to Yemen and I was forced to shoot myself to leave the battle," he says. "Now the Saudis are firing Yemeni fighters from Saudi.

"This is a clear indication that there are huge numbers of Yemenis joining the battles on the Saudi borders to protect Saudi, and this is a normal increase amid the economic crisis as Yemenis are starving to death."

Tawfeeq's leg has healed: if he wanted then he could, theoretically, return to the battlefield. But he labels such work as “dirty”.

Others are conscious of the tensions that the return of thousands of unemployed men may place on Yemeni society.

"I am unemployed. I work as a builder and delivery driver and my return may deprive other workers of their work," says Ali. "We are definitely competing with workers in our communities for work, but we do not have any other choice."

We are definitely competing with workers in our communities for work, but we do not have any other choice

- Ali, unemployed

The only chance that many fighters have for earning money is to join anti-Houthi units close to where they live.

Abdullah, one of the leaders of the Popular Resistance in Taiz, said it was willing to recruit returning fighters. "We do not support the idea of joining the battles of the Saudi on their borders as we need Yemeni fighters in Yemen to liberate Taiz and other provinces.

"We are willing to recruit the fighters who returned from Saudi and give them irregular salaries as all Yemeni fighters in the local fronts."

But the wages for fighters in Yemen, at $130 per month, are less than a quarter those fighting on the Saudi front.

Walid concurs. “At first I was sad to leave the battlefield as I will not get a salary,” he says, “but now I believe that it was good for me as safety is the most important [thing]."

"Today I can move in the streets, meet my friends, sleep when I want, get up when I want and there are no military commands anymore. Moreover, I do not have to worry about being killed. This is enough reason to stop fighting."

And Ali? After two days back home, he confessed to his friends and neighbours what he had done and expressed regret. The reaction was mixed: some understood, but others now regard him as a mercenary and as someone who had sold out his country for the sake of money.

Like other fighters who have come home, he can no longer travel to Houthi-controlled areas, fearful that they will kill him for what he now regards as a mistake.

Before he joined the battle, he says, he was at least a free man. Now he cannot leave the liberated areas of Taiz. "I cannot travel to look for work in Sanaa and other Houthi-controlled provinces. I live in a big prison."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.