Between Istanbul and Kabul: Afghan-American woman becomes philanthropy icon

Mahnaz Safi has only been to Afghanistan twice, and most of her first trip was spent with a family in a small village in the northern province of Balkh, with the remainder spent in Taliban detention. Still, the 30-year-old Afghan-American from Virginia quickly earned herself a reputation in the cities of Mazar-i Sharif and Kabul as the “the girl who gives people money”.

Safi takes pride in being able to help Afghans at a time when western-imposed sanctions and aid cutbacks have made 24.4 million people dependent on emergency relief to survive. But others fear that her reputation for helping people could put her in danger.

Safi says that she was urged by Taliban guards near the central Kabul apartment building where she was living this summer to consider relocating.

'The Taliban came to me and said, 'people know you live here and they ask for you by name, expecting money. It's not safe to stay here'

- Mahnaz Safi

“They came to me and said, ‘people know you live here and they ask for you by name, expecting money. It’s not safe to stay here’,” she tells Middle East Eye.

But Safi is undeterred, saying that her current efforts in Afghanistan and Turkey, where she assists Afghan refugees, are part of a lifelong goal to give back. “I admit, people knew me as ‘donation girl’, but I like to find a way to make an impact, to do something for people,” she says.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Sitting in a hip Kabul eatery that is often featured on Afghan social media, Safi says something that seems out of place for a budding influencer, but is in line with an amateur humanitarian coming up in the social media age: “I don’t ever want the story to be about me.”

Safi says she first understood how bad the situation was for Afghan refugees when she visited Istanbul this spring. Like most Afghans in the US, Safi had very little understanding of the situation facing her compatriots who had fled to Turkey after the Taliban’s return to power last August.

They had no idea about the racism and anti-refugee sentiments Turks have increasingly taken to posting online. Nor did they know that thousands of Afghans had been deported back to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan this year. It was while in Istanbul that, Safi says, she saw the living reality for many of the 183,000 Afghan refugees in the country.

'Devastating'

Afghans, she says, “are so looked down upon in Turkey”.

Hanging out with Afghan refugees in their 20s and 30s, Safi met young men “who went from having degrees to serving people” by collecting trash and working in restaurants and shops.

At first, Safi was confused. These were bright, talented young men. Some had degrees and spoke English well. Why would they leave Afghanistan to essentially squat in run-down buildings in the hidden corners of Istanbul?

“I saw on the news that the sanctions were making people poor and hungry in Afghanistan, but it wasn’t until I started talking to the refugees in Turkey that I really understood how bad it was,” she says. “They would tell me about their families back home. It was devastating.”

Safi speaks to MEE from a Kabul sports lounge that has returned to being a hangout for young Afghan men, and even some women, in recent months. With TVs broadcasting different sporting events, a PS4 and $11 shishas, it is a far cry from her experiences with Afghans in the rundown neighbourhoods of Istanbul and the flood-damaged districts of Eastern Afghanistan. She immediately takes a picture of the restaurant for the 130,000 people who follow her on TikTok and the nearly 6,000 others who keep up with her travels on Instagram.

Though the photos of the lounge seem out of place with the videos of children and women lining up to receive cash, food and clothing that she and her small team hand out, she hopes they will show the contrasts of life in Taliban-run Afghanistan.

What she didn’t realise, though, is that in a nation where 97 percent of the population risks falling below the poverty line this year, desperation can easily take hold of people.

'Donation girl'

In June, there was a knock on the door of the house of the Balkhi family where she was staying. It was the Taliban.

They had come to inquire about the “donation girl”; how she, whose family hails from the northern province of Panjshir, was related to the family of ethnic Turkmen, and where exactly the money she was handing out had come from.

Initially, she managed to assuage the Taliban, but by the next morning, they were back.

After that, Safi’s online feeds went silent. Her followers, who had tracked her movements between Virginia, Istanbul and Kabul online for months, sensed something had gone wrong. Her family and friends immediately reached out to anyone they could get in contact with in Afghanistan, including two other Afghan-Americans.

Because she was advised to carry an emergency phone along with the new one she had purchased shortly after being robbed in Kabul, it was almost impossible to prove her innocence, or even post updates to her thousands of followers.

“I kept saying I can prove that the money came from online donations if I could only access my emails,” Safi recalls. But she was foiled by the run-down state of the detention centre in Jowzjan province. “One [phone] had no charge and on the other one, Google and Instagram kept asking for verification codes that I could only access on the other phone. It was a mess.”

'We won't hurt you'

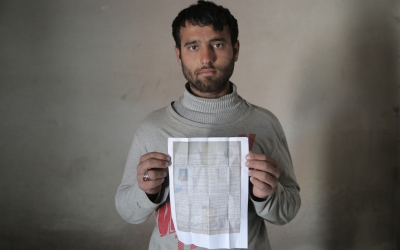

A lack of proper paper documentation meant she had to wait for more than a week in the detention centre.

She spent much of her time huddled in a corner of the room she was being held in, separated from the other women. She would later find out that some of the women were being held on charges of committing "moral crimes", including running away from home and having sex outside marriage.

Safi says she was treated very well in custody by the Taliban and the other women being detained, who referred to her as their “sister” and a “guest”.

She recalls an interaction on one of her first nights in detention when she heard a voice from behind the curtain that had been placed in her room to keep the Taliban men from looking at her. “Hey, why are you scared, we won’t hurt you, you’re our guest,” the male voice said from behind the curtain, she says.

After that, she resolved to calm herself. Her first step was to make friends with the other women. The more she spoke to them, some with their children at their side, the more she was surprised.

“Some of them were badmash, everyone kept away from them. But the others would sit with each other, laughing and joking, dancing and singing,” Safi says. “You understood they were just trying to make the best of the situation.”

Even in detention, she couldn’t escape the spectre of poverty.

“One of the women said to me, ‘I’m happy here. I at least get fed and don’t have to go home hungry’. It was devastating,” Safi says.

It wasn’t just the women, though. Even the guards started talking to her. They were fascinated by what the West, and particularly the US, thought of the Taliban. She told them it wasn’t good.

Released

In the year since the Taliban’s Islamic emirate returned to power last August, there have been hundreds of allegations of abuses against Afghan journalists, former security forces, female protesters, and ethnic minorities that were documented by The New York Times, The Washington Post, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and The Committee to Protect Journalists.

The Taliban guards who watched over Safi lamented this image and hoped their treatment of her and the other women in detention would counteract that image.

'They all just wanted to talk about the Taliban and wanted me to say I was treated badly, even though I wasn't'

- Mahnaz Safi

However, rights workers, journalists and aid workers, who had followed Safi’s case, said the protection afforded to her by her foreign passport, even with her Afghan roots, should not be discounted.

Eventually, after nine days in detention, she had her day in front of a Taliban official.

They had managed to find a charger for her phone and so she was given the chance to tell her story in full, complete with emails showing the $70,000 she had raised through crowdfunding and photos and videos of her distributing bread, cookies, money, shoes, and clothes to people in Kabul and Mazar.

She was free. But soon after, she was reminded of that Persian saying when she found out why she had been detained. Someone she wasn’t able to give money to in Mazar had gone to the Taliban accusing her of converting people in exchange for aid and being funded by western propagandists.

'I cried my eyes out'

“The need in Afghanistan is so great. You try and help as much as you can, but you’ll never reach everyone,” she says.

Safi says the time spent in detention won’t keep her from trying to assist the Afghan people. “I have to help the people,” she says. “How do I see all of this poverty and all of this need and not do something?”

Soon after being released, she travelled to Dubai. It was there that, despite her best intentions, the story became about her.

“I had all of these messages and emails from journalists wanting to talk to me,” she says.

At first, she replied, but again, she was quickly disheartened.

“They all just wanted to talk about the Taliban and wanted me to say I was treated badly, even though I wasn’t,” she says. “Every time I told them they were nice to me, the journalists lost attention or tried to get me to say something bad.”

Of course, based on reports of the torture of Afghan journalists and allegations of the detention and abuse of female activists, people familiar with such matters say Safi’s treatment was very likely impacted by her foreign passport.

Safi laments that everyone wanted a story about the Afghan-American girl and the big, bad Taliban, not the millions who are unemployed and hungry, which was the actual story she wanted to get across to audiences in the West.

“On one of my first nights [in Kabul] I cried my eyes out,” she says. “I kept seeing those desperate people who were just asking for some food.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.